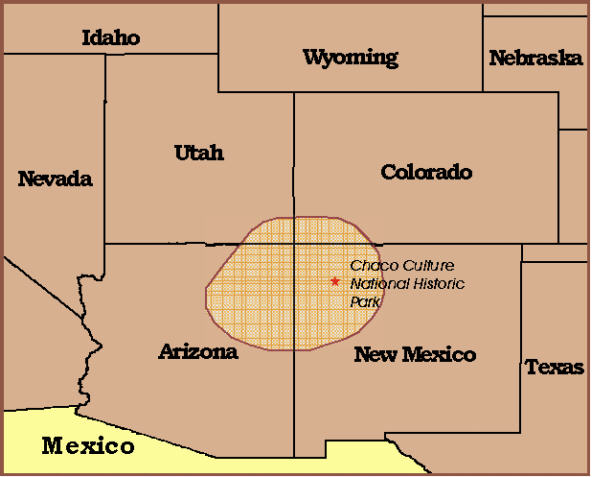

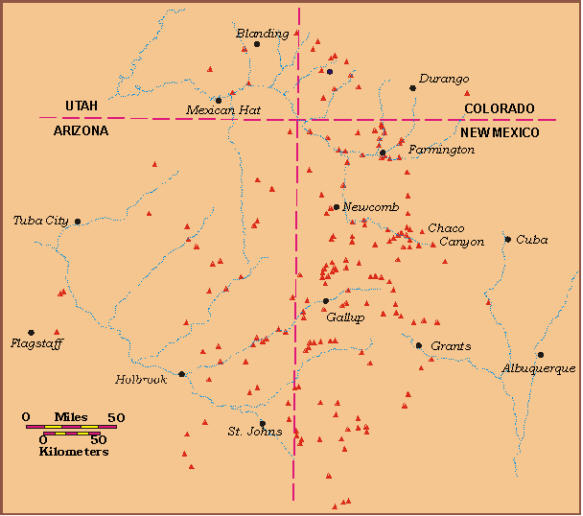

Figure 1: Area of Direct Anasazi Influence

Several diverse geo-spatial technologies are being used to improve research results in Chaco Culture National Historic Park. The McKinley County GIS Center, the Navajo Nation Chaco Protection Sites Program, and the National Park Service are working together to establish non-destructive methods for archaeological research. At the heart of this new research is data integration within a rigid geo-spatial context. There will be specific examples of how the data are integrated using ArcView, and the results achieved from data integration. After over 100 years of scientific exploration, this innovative approach to Chaco Anasazi research is opening new windows into the past.

The use of geo-spatial technologies, specifically remote sensing and photogrametry, is not new to research in Chaco Culture National Historic Park. Various remote sensing technologies were extensively used by the Remote Sensing Division of the National Park Service in the 1970’s. New to the use of geo-spatial technologies in research activities is the ability to integrate geo-spatial data of disparate sources and scales into a rigid geographic framework that allows researchers to view and query the data in a single environment. The cost of the development and use of these data has also dropped significantly in the past few years, making remote sensing and GIS a very cost effective research and resource management tool.

INTRODUCTION

Recent advances in geo-spatial technologies have dramatically altered the potential for large scale, non-invasive investigations of past cultural landscapes. These new technologies have also narrowed the gap between short term "pure" research and long term "management" of cultural landscapes, in part, because they facilitate the integration of data from many disparate sources within a single rigid geo-spatial context. ArcView has become a critical tool for cost effective integration, manipulation and visualization of the complex spatial, tabular, and image data required for pre-Columbian landscape reconstruction.

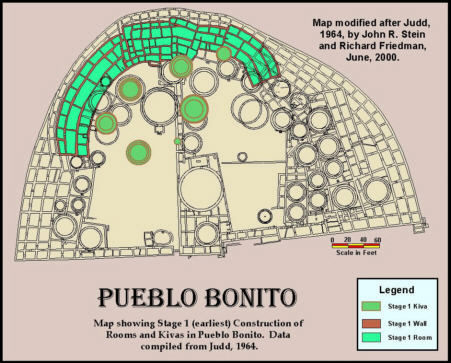

This paper describes one facet of an ongoing cooperative effort by the McKinley County GIS Center, the Navajo Nation Historic Preservation Department and the National Park Service to build a GIS data base and promote nondestructive research on Chaco-related resources. Herein, we focus on the Pueblo Bonito Ruins, located in Northwestern New Mexico, within Chaco Culture National Historical Park. Pueblo Bonito is the acknowledged center of a vast pre-Columbian empire that controlled over 74,000 sq. miles in the Four Corners Region of the American Southwest (figure 1). Covering approximately three acres, Pueblo Bonito contains over 350 rooms, approximately 50 kivas, and was five stories high. With ceiling heights of 12 to 15 feet, the rear portion of this building may have towered upwards of 75 feet above the Canyon floor. Based on tree-ring and ceramic assemblage dates, Pueblo Bonito has an estimated construction and use history of 500 years, from 800 to 1300 AD. Pueblo Bonito embodies several episodes of massive construction. These construction episodes were often accompanied with selective razing of portions of the building. Pueblo Bonito represents the most complex achievement of pre-Columbian architecture in the American Southwest.

Figure 1: Area of Direct Anasazi Influence

PROBLEM

This paper describes the work derived from an administrative relationship between the National Park Service-Chaco Culture National Historical Park and the Navajo Nation, directed specifically toward management of Chaco Period remains on Navajo Lands. This relationship is mandated by legislation and supported by special Congressional Allocation. While this is simple in theory, in actual practice it is complicated by practical matters that include but are not limited to ceilings on funding levels, administrative complications, differences in management objectives and constraints, and sheer geographic scale. The area of the Navajo Nation is approximately 17.5 million acres and encompasses an estimated 150 to 200 communities of remains affiliated with Chaco Canyon. McKinley County itself is an area of 3.3 million acres that coincides with the Southeastern area of the Navajo Nation, and encompasses Chaco related remains under NPS and Navajo Nation jurisdictions as well as other federal, tribal, state, local government and private jurisdictions. The National Park Service - Navajo Nation - McKinley County partnership is established and maintained by a Memorandum of Agreement.

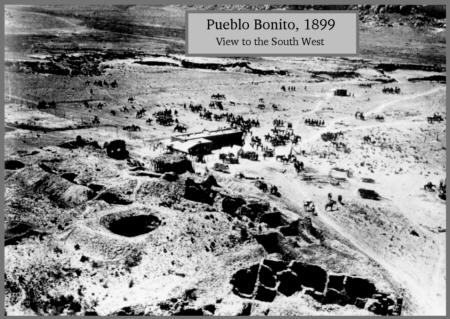

It is no accident that we selected Pueblo Bonito as the focus for this study. Pueblo Bonito is perhaps the most extensively studied pre-Columbian structure in North America. By the early 20th century, this building had been almost completely excavated, mapped and developed as an exhibit. Thousands of artifacts had been recovered and shipped to museums in the eastern US. A prolonged struggle for control of Pueblo Bonito and its contents by federal, state and private interests established this one building as the source of the southwestern archaeological paradigm, and the focus of the debate that culminated in the Federal Antiquities Act of 1906, the establishment of Chaco Canyon National Monument in 1907 and ultimately the establishment of Chaco Culture National Historical Park in 1980.

Over 100 years have passed since the first exploration began at Pueblo Bonito, and there are still many questions about the building, including it’s role in the life of the Anasazi, and the many building phases that it went through. A century of invasive archaeology, ranching, trading, ruins maintenance, and cycles of infrastructure development and demolition has extensively reshaped Pueblo Bonito and the pre-Columbian landscape that surrounds it. A crisis has arisen in the management and interpretation of ancient landscapes generally and the Chaco landscape specifically. There are many contributing factors to this crisis. These include ignorance of, or misunderstandings by archaeologists about the nature of the extensive landscape architecture outside the walls of the larger buildings that have resulted in both passive and active obliteration or obfuscation of significant pre-Columbian features. Some of these misunderstandings are enshrined in the literature of Southwestern Archaeology and can be traced to back to their source, however, many others have entered the oral history of southwestern archaeology as conventional wisdom and the source remains unknown. Precious little documentation is available on the nature and location of the spoils from archaeological excavations, placement of extramural trenches, informal tracks or structural remains that have now become a part of the landscape and a part of an interpretation and management problem.

Increasingly restrictive requirements for invasive archaeological research, and the high cost of such research have contributed to the current emphasis on non-invasive technologies. There is an irony here. These technologies are related to resource management and research to aid in resource management. The intended as well as unintended results of archaeological investigation and the recollections of archaeologists about the nature of these results has become a domain of interest in reconstructing the Chaco landscape. Much of the information critical to reconstructing the Chaco landscape may also be found in the oral histories and anecdotal recollections of local Navajos and Park staff.

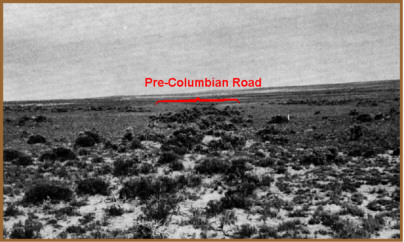

A key component to our understanding of Pueblo Bonito, and the Anasazi in general, is documenting the landscape features that are associated with the Great Houses. The best known of these landscape features are the pre-Columbian roads (figure 3). Until recently these features have received little attention from archeologists, and were only briefly mentioned by Judd, and not addressed at all by Pepper. The Remote Sensing Division of the National Park Service provided the first glimpse of the extent of the Chaco Road System in the 1970’s, and the BLM Roads Projects of 1980’s provided detailed documentation of selected Chacoan Roads in the San Juan Basin. Despite these efforts, the roads and associated landscape features remain largely undocumented, and are still considered a curiosity rather than a resource by a vast majority of the archaeological community.

Perhaps, one of the reasons for this apparent lack of interest by the archaeological community can be found in the requirements for landscape feature identification and documentation. The identification of these features requires the researcher to have a unique set of skills that aren’t a part of the traditional archaeological curriculum. For field observation, the observer must have an intimate knowledge of interrelationships of the geography, geology, geomorphology, soils, and vegetation of the area. This knowledge must then be critically applied through understanding both the natural and/or cultural forces that have been applied in a particular location, and their physical manifestations on the surface over time.

In addition, one of the most effective tools for landscape feature identification and documentation is aerial photo interpretation. Photo interpretation for cultural resources is more of an art, than a learned skill. In "Remote Sensing, A Handbook for Archeologist and Cultural Resource Managers" (1977) Lyons and Avery define these requirements very well in the following:

If some of the desirable mental traits outlined here appear difficult to measure, it is also true that they are more-or-less ingrained or "imprinted" characteristics, i.e., they are not acquired as a result of on-the-job training. In brief, the best potential candidates as image interpreters are discovered and not made."

Lyons and Avery also provided the following insight the knowledge and association skills required for successful interpretation of cultural features.

After reviewing the requirements for landscape feature identification, it can be easily understood that for many people, landscape features, and particularly pre-Columbian roads, are at best, very difficult for the average person to see. One could easily infer that for much of the archaeological community, these features are truly invisible, which could explain why they have been largely ignored for the past 100 years. But to those with the required knowledge and skills, they can be easily recognized and documented.

OBJECTIVES

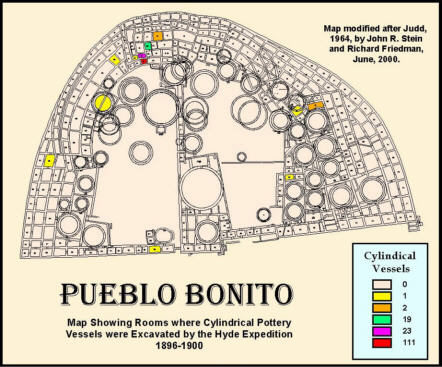

The objective of this project is to define methods and procedures that can be used to build an integrated database that will document Chacoan great houses and reconstruct their associated pre-Columbian landscapes. Several of these landscapes are currently being investigated and documented by this partnership. The objective at Pueblo Bonito is to develop strategies that can be used to integrate data collected during excavations, information obtained from interviews with local Navajos and people who have worked in Chaco, and information obtained from remotely sensed data to reconstruct the pre-Columbian cultural landscape that has been intensely modified by "modern" man. Ultimately the project will be expanded to include the related great houses and great kivas of Chetro Ketl, Pueblo del Arroyo, Casa Rinconada, Kin Kletso, Pueblo Alto and the primary landscape features that interconnect these structures.

With over 145 Chaco related great houses in the Four Corners Region (figure 4), the long term objective is to develop consistent strategies for data base development and landscape reconstruction for managing these valuable cultural resources. The short-term goal is to critically evaluate and reconstruct what is, and what is not, pre-Columbian within the core of the Chaco landscape, and to critically evaluate the quality and credibility of the recordation and interpretation of features in the core area of the Canyon.

Figure 4 - Chocoan Great Houses in the Four Corners Region

RESOURCES

The resources required for documenting and reconstructing the pre-Columbian landscape are as diverse as the cultural properties themselves. Reconstructing the landscape of Chaco Canyon requires the skills and observations of a team composed of many professionals, and other knowledgeable individuals. First hand knowledge of the extensive landscape modification from the earliest archaeological excavations no longer exists within living memory. Knowledge of events from the post war era is very limited and will pass out of living memory in the very near future. First hand knowledge of work performed in the 70's and 80's will be available for another decade or so but several key persons have already passed on and taken their memories with them. Critical resources that have been virtually ignored in the past are the Navajo Staff at Chaco Park, the Navajo communities bordering on the park and the applicable content of Navajo oral history and ceremonials. The Native American community holds a wealth of information about the configuration of the Chaco Landscape.

First hand written accounts in the form of original notes, sketches and maps in journals, legal documents, administrative reports and publications are another very important source of information for this study. Noteworthy in this regard is the results of the Hyde Exploration Company’s excavations at Pueblo Bonito from 1896 - 1900 (Pepper 1920) and the National Geographic Expedition excavations from 1920 - 1927 (Judd 1954 and 1964). Likewise, the ruins in Chaco Canyon have been extensively photographed since the latter 19th century, before the major excavations began. The terrestrial photographic record is a primary source of information about structures or features of the landscape that are now buried or obliterated.

Aerial photography is the most important source of information for this study. The photography provides the framework for the creation and management of the wide range of information that is represented by the geo-spatial database. In the digital medium, aerial photography is an analog landscape amenable to exploration, annotation and interpretation. Low level oblique aerial photographs of Pueblo Bonito were first acquired by Charles Lindberg in 1929; two years after the conclusion of excavations by the National Geographic Society at Pueblo Bonito but prior to the major excavation at Chetro Ketl by the University of New Mexico. Five years later, in 1934, Fairchild Aerial surveys Inc. flew the first photogrametric stereo black and white imagery of the Canyon at a nominal scale of 1:28,000. Over the years, numerous air photo missions have targeted Chaco Canyon or Chaco related locations. A great variety of imagery is available, from Russian satellite imagery to low level multi-spectral data acquired by NASA in 1994.

Resistivity, Ground Penetrating Radar, and Magnetometer geophysical surveys are being conducted in select locations to acquire subsurface image data. This information will be compared to descriptions and photographs of now buried structures, conventional maps of surface features, plots of surface material distributions, Digital Elevation Models, and aerial imagery, to establish conditional criteria for optimum use of these data. High resolution LIDAR elevation data, and color orthophotos from digital photogrametric cameras, are also being evaluated for cost and data quality in comparison to similar data generated from softcopy photogrametry. Focused studies by specialists in professional fields including soils, biochemistry architecture, engineering, geology, and linguistics are additional resources that are critical to the successful mapping and ground truthing of the Chaco landscape.

METHODS

The heart of the reconstruction process employs the use of softcopy photogrammetry and GPS to create a rigorous geo-spatial framework. For this project, the framework is generated from two sets of conventional black and white imagery, one at a nominal scale of 1:3000 and one at a nominal scale of 1:6000. This imagery was acquired by Koogle and Pooles Engineering in March of 1973.

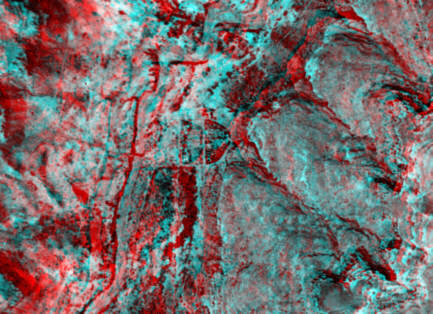

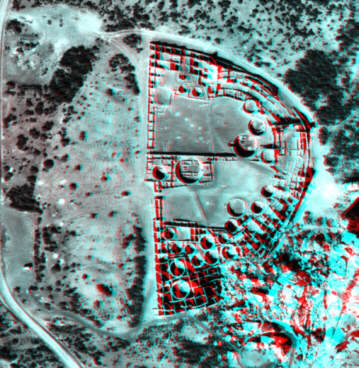

Red/Blue Stereo Anaglyph Images of Pueblo Bonito

Left Image taken in 1934 Right Image taken in 1973

The base imagery was geo-referenced using centimeter level GPS data acquired in the field specifically for this project. Geo-referencing the base imagery facilitated the construction of an accurate DEM of the central Chaco Canyon landscape, including Pueblo Bonito. Once it was geo-referenced, the base image served as an accurate source of information on a variety of problems, such as the height of standing walls and the proper locations of walls and exposed floor features. Establishing the height of standing walls is essential to the Pueblo Bonito database, however collecting this information in the field would have been difficult, dangerous and prohibitively expensive. The form of Pueblo Bonito varies somewhat from map to map. The nature of these discrepancies indicates distortion introduced in the mapping and printing process. Map errors have been perpetuated and even exaggerated through "artistic license" while on the drafting table, and many generations of printings. Once translated into the digital medium, archival maps of Pueblo Bonito may be registered to the geo-spatial framework, thus removing enough distortion create compatible layers of spatial information. This process is also applicable to image layers where the camera geometry is unknown, such as the 1934 Fairchild photography.

Ultimately, after all spatial, tabular and image data have been integrated into spatially accurate data sets, they will be converted to data formats compatible with ArcView. By standardizing the data on a common platform, it can be easily accessed and used for a wide variety of management and research applications.

CONCLUSIONS

The use of geo-spatial technologies, specifically remote sensing and photogrametry are not new to research in Chaco Canyon. In the 1970's these technologies were used successfully by the Remote Sensing Center of the National Park Service. However, the ability to integrate spatial, tabular and image data of radically disparate scales and sources into a rigid geographic framework that allows researchers to view and query the data within a single environment is new. The cost of development and use of these data have dropped significantly in the past few years making remote sensing and GIS a very cost effective research and management tool.

Authors

Richard Friedman

Director of Computer Services

County of McKinley

2105 East Aztec Ave.

Gallup, NM 87301

phone: 505-863-9517

fax: 505-722-9317

e-mail: gismc@cia-g.com

John R. Stein

Supervisory Archaeologist

Navajo Nation Division of Natural Resources, Historic

Preservation Department

Chaco Protection Sites Program

2105 East Aztec Ave.

Gallup, NM 87301

phone: 505-863-9517

fax: 505-722-9317