This paper synthesizes cultural anthropology and archaeology: it promotes mythology as a historic source for archaeological research, and uses GIS to help interpret mythological and geographical data relevant to the Celts of pre-Christian Ireland. The ArcView program establishes correlation between geographic characteristics and pre-Christian Ireland's mythology, recorded in the dindshenchas - a collection of legends describing the origins of Irish place-names. Routes are predicted by ArcView using a cost analysis query procedure and sites from the dindshenchas known to associate with the roads, thus providing archaeological reference to the Five Roads of Tara, the ancient Seat of Ireland's High Kings.

There are, in anthropology, several themes that continually challenge the attempt to understand the past. Among these themes is the dichotomy presented by the notion that both cultural continuity and cultural change occur over time. It is the attempt to understand this dichotomy and explore the mechanisms of continuity and change that provide anthropology and its subfields of archaeology, linguistics, cultural anthropology and physical anthropology with fascinating questions. In response, each subfield has developed its own favorite theories and methods of investigation, thus causing a degree of divisiveness within anthropology as a whole.

Anthropology's strength is its depth and breadth, but its divisiveness as a discipline is its weakness. This division is apparent despite the fact that many anthropologists deny it, claiming "holism" as their mandate. Perhaps this lack of unified vision in anthropology is caused by the tensions inherent in theoretical and methodological approaches to the study of humanity: is anthropology scientific or is it humanistic? Should we be subjective or objective in our research? Should we focus on human culture in the general or the particular?

Confronting these issues has made archaeologists realize that it is no longer enough to merely list the traits of a culture; culture must be interpreted. Immediately after accepting such a directive, archaeology accepts subjectivity as one of its own traits. Objective interpretation is an oxymoron. The discipline is full of theory, method, hypothesis testing, and all manner of other hard science terminology. This desire to portray anthropology, and therefore archaeology, as "hard science" is unfortunate: one can objectively describe an archaeological artifact; one cannot objectively determine or understand the true meaning of that artifact, thus one cannot actually determine complete truth about the culture and people to which the artifact belonged. Still, anthropology and archaeology both attempt to refine hypotheses regarding culture and meaning by examining observable patterns in available data.

Traditional methods of archaeological theory tend to approach the problem of scientific analysis by making analyses of the evidence, which are based upon a kind of computation: if the evidence shows a, b, and c, then x, y, and z are proposed as a hypothesis to explain the observations about the culture or people. Often the hypothesis becomes an archaeological "sacred cow," regarded as a truth. Archaeological algebra of this sort may sound scientific, but it is not more factual than an honest and forthrightly admitted subjective opinion.

Archaeologists try to understand past cultures and peoples from excavated material remains, answering questions about "how people lived" by interpreting people's manufacture and use of tools, looking at patterns of settlement to aid in interpreting social and political hierarchies, and delineating religion with ritual artifacts, motifs, and structures. Traditionally, descriptive analysis of the archaeological evidence based on either a symbolic, functional, or material approach results in conclusions regarding way of life, cultural continuity and cultural change. Such analyses do not take into account the thought processes of the people who executed the changes. Change is said to have occurred - at such and such time, a particular people stopped practicing one ritual and adopted another, for example. Some external force might explain such a change: the climate, environment, an invading people imposed or introduced new rituals and beliefs, etc. In other words, change is described but not necessarily understood. In contrast, cognitive archaeology attempts to understand, for example, how people's thoughts about ritual might have changed, which might result in a change in material evidence.

In the context of cognitive archaeology, which is geared towards more than just cataloguing artifacts and excavating sites, archaeological studies have used Geographic Information Systems (GIS) to organize, analyze, and interpret archaeological data. GIS are tools that can - and are beginning to - revolutionize the way in which spatial analysis is perceived and used in anthropology. For much of the history of archaeological research, space has been perceived and defined as sites, regions, and areas that are investigated with a focus on, but not limited to, diffusion theory, evolutionary theory, distribution analysis, settlement patterning, and similarities in artifactual evidence. Cultural anthropology has primarily investigated relatively small spatial scale - most notably in ethnographic work, where the village, its inhabitants, and possibly the nearby region are the focus of the ethnographer. Aerial photography, cultural geography, and ecological (or materialist) anthropology all contribute to broadening the spatial scale of anthropological research. Referencing human activity to the ecosystem concept enables the anthropologist to examine temporal and spatial considerations of the human/environmental relationship. One result of these methodological and theoretical innovations is awareness on the part of anthropologists that GIS applications can broaden the focus of the archaeologist's work, without losing the details of particular archaeological site or region analysis.

Archaeology has recently been exploring non-intrusive methods of investigation: remote sensing techniques, like satellite, sonar, and radar imaging, are being hailed as "new" archaeological methods. Most of the work being done in archaeology with these non-intrusive methods is within the realm of cultural resource management (CRM), focusing on predicting site location before development. GIS are most often used for the following purposes: 1) regional data management; 2) management of remotely sensed data; 3) regional environmental analysis; 4) simulation; and 5) locational modeling. Locational modeling, used to predict locations of a particular manifestation of human behavior on the physical landscape, becomes more accurate and spatially defined with GIS than with other methods. Spatial scale and a synthesis of human effect on and relation to the physical environment are key elements in GIS-based locational modeling. Locational modeling, therefore, is an obvious and natural choice in synthesizing a cognitive perspective and geographic phenomena, whether man-made or natural.

Cognitive archaeology has much to offer in the quest to understand the past, even as a relatively new approach to archaeological interpretation, as it attempts to interpret the thought processes behind human behavior evident in the physical remains of human existence. It seeks to answer "anthropological" questions about past human cultures, questions concerning political organization, social hierarchies, family and kinship structures, and religion. Closely related to cognitive archaeology is modern landscape archaeology, which acknowledges that human interaction with the landscape goes beyond mere settlement patterns. The earth is often seen as sacred and animate, with many natural features being named and playing important roles in that interaction, though they may show no signs of human activity. These recent archaeological theories provide methodologies that try to come to terms with the true nature of anthropology and archaeology by looking at the evidence and then concluding that it might mean something if the natives of the culture thought in a particular manner. Interpreting cultural remains is often informed guesswork.

Traditional descriptive, functional, and symbolic approaches to archaeology are still effective and contribute to general knowledge of cultural change and continuity. Nevertheless, understanding the cognitive processes that produced and preserved rituals and beliefs would be helpful in understanding the worldview of ancient peoples. Using mythological information as a means to inform on religious beliefs is a way of presenting a people's worldview. Mythological data can establish correlation between what the people "thought" in relation to the land upon which they lived and how, in consequence, they "used" the land in relation to their religious beliefs.

Religion, mythology, and other human systems of belief and action are commonly considered the special interests of cultural anthropologists, not archaeologists, while tools like GIS are used more by archaeologist than cultural anthropologists. Therefore, using GIS with mythological data is one way to synthesize some of the methodological questions posed and to provide some resolution. Some data associated with cultural phenomena have no conventional connection to archaeology; this is true of the dindshenchas, the mythological place-name legends used as a data source in this project. Normally, archaeologists focus on a material culture, excavate a site, collect and organize the artifactual data, and then perhaps use "outside" sources like mythologies or the ethnographic record to aid in cultural interpretation. This project does the reverse - to begin with "outside" sources (i.e., the place-name legends) and non-intrusive tools (i.e., GIS) to establish archaeological significance.

The first Christian missionaries in Ireland found that the people of the Celtic religion held beliefs that made conversion relatively easy. Similarities in doctrine - for example, both the Christian and Celtic religions emphasize trinities - gave early missionaries a head start. It became explicit Church policy in AD 601 for Christian missionaries to incorporate elements of local pagan religions into Christianity, making conversion easier. The written recording of dindshenchas - a collection of pre-Christian legends describing the origins of Irish place-names - by early Christian Irish monks (who were the remnants of the traditional learned class of Celtic Ireland) is evidence for both religious change and continuity in Irish culture.

The influence of the ancient Celtic religion continued in Ireland after the conversion to Christianity. One of the strongest indicators of this influence is that in the latter half of the Middle-Irish period (the latter half of the 10th Century AD), the prose versions of the dindshenchas were recorded. In the 10th, 11th, and 12th centuries AD, the metrical version of the dindshenchas were recorded. Long after Christians populated Ireland, elements of Celtic religion were deemed important enough to motivate Christian scribes to record the legends. The preservation of the old religion's legends indicates that early Christians in Ireland recognized the tales as possessing value beyond pagan mythology. The survival of many of the place-names today proves both cultural continuity and the fact that the dindshenchas were stories of real places, illustrating that the dindshenchas represent more than mere literature.

Cultural continuity in Ireland is evident in many things, including the continued use of pre-Christian place-names by contemporary people (some of the names have been anglicized), and by the continued use of the Celtic cross, which superimposes the Celtic religious symbol of a circle upon the Christian cross. From any construction period after the Christians came to Ireland, the ornately designed stone Celtic crosses can be identified, carved upon religious and non-religious structures alike. Continuity can also be found in the "reconsecration" by Christians of traditional pre-Christian sacred sites, where the ancient Celtic name for Croagh Aigle (Great Mountain) has become Croagh Patrick (Patrick's Mountain). However, the mechanisms of continuity and change are difficult to trace. Combining elements of cultural anthropology and archaeology addresses this problem.

This project looks at the culture of pre-Christian Ireland's Celts, and synthesizes cultural anthropology and archaeology. Esri's ArcView 3.2a is used to assist with the interpretation of mythological and geographic data, establishing correlations between geographic characteristics and pre-Christian Ireland's mythology. The dindshenchas are used as a historic source for Irish prehistory, much of which is unclear. The dindshenchas are in metrical and prose form, with 770 places mentioned in the legends. These place-name legends relate ancient stories of how lakes, streams, rivers, fords, estuaries, islands, hills, cairns, ridges, plains, mountains and other geographic features of Ireland were given names. The dindshenchas preserved traditional knowledge by one tier of Ireland's learned class (the druids), primarily in poetical form to aid memorization, because they placed a religious prohibition on writing in order to keep their knowledge from falling into the wrong hands. The earliest written records of Ireland give us only a glimpse into prehistoric Ireland's life in the ages before writing developed; for example, druid scholars would spend up to twenty years memorizing the dindshenchas and other traditional texts. Ireland remained pagan, or Celtic, until the early fifth century AD. The tales were written down in the tenth and eleventh centuries, but the date of the true origin of these tales is shrouded in the proverbial mists of time, although there are linguistic hints that much of their content dates at least to the Late Iron Age.

Druids were the intellectual-class of pre-Christian Ireland's Celtic people, associated with following the Tuatha De Danaan (People of the Goddess Danu), who are generally recognized as the Celtic deities. As early as 500 BC, Hecateus of Miletus identified the "Keltoi," having come from the headwaters of the Danube, the Rhine, and the Rhone rivers, as the mythological and legendary people known as the Tuatha de Danann. This project examines dindshenchas place-name sites that are associated with druids. Druids are mentioned in the tales either as characters in various legends of how sites received their names, or as being significant to the religious rituals pertaining to a site after it received its name. The druid association, as an obvious religious motif, may help delineate other religious motifs or geographic characteristics that sacred sites have in common.

The dindshenchas are full of mythological information about pre-Christian Ireland, yet they offer much more; links to historic genealogies, references made to battles, wars, kingships, royal marriages, and family lineages. There is also some etymological evidence hinting at the deeply rooted druidic influences and beliefs held by the ancient Irish (see Appendix A). These cognitive connotations associate elements of pre-Christian Ireland's worldview with aspects of the ancient religion. Nevertheless, there are words in the dindshenchas that come from the dru/a/i root word (meaning "strong"), which do not translate as either "druid(s)," "druidess," "wizard," "wizardry," "magic," or "magical." There are words that associate with strength, and lust (an earthy and powerful force), and the word that translates as "hill" or "ridge" is druim/m. Ireland is peppered with hills and ridges. The suggestion is that the ancient people of Ireland chose to name these dominant geographic features accordingly with their strong belief in the Celtic druidic forces, a choice that reflects the predominance of druidic influence from long ago.

The tales contain complex stories of the interactions between deities, royalty, druids, heroes, and heroines that resulted in place-names for particular geographic locations on the Irish landscape. An example is the tale describing how Dublin was named. Dub, a druid priestess, desired the husband of a woman named Aide. Dub cast a spell upon Aide's home, whereupon the sea rose up and swallowed the entire household. Aide's father then sent his greatest warrior to kill Dub; the warrior knocked her in the head with a rock hurled from his slingshot. She fell into "the pool" and drowned. The Irish word for pool is "lind," thus the site was named "Duiblind," Dublin, as we know it today. (Incidentally, no site was named for poor Aide.)

The dindshenchas, like most mythologies, are commonly perceived as simply a body of literature, although they are sometimes recognized as containing information about Ireland's pre-Christian religious beliefs. However, the data found in the tales suggest they are a legitimate historic source that can be used with GIS in archaeological research on the Celts of pre-Christian Ireland. Specifically, this project focuses on 46 sites from the dindshenchas that were significant to druids and 16 well-known prehistoric Irish sacred sites. The 16 well-known prehistoric sites are locations that are both mentioned in the dindshenchas and deemed sacred by early inhabitants of Ireland. Some of these 16 sites were later reconsecrated by Christian missionaries, while others have retained their pre-Christian sacred reputations into the present. Using ArcView, the two distributions will be queried to see if there is degree of feature correlation or a pattern of geographic overlap, which would illustrate a definite connection between traditional religious data found in mythological tales (represented by the stories involving druids) and geographic sites known to be sacred.

The two distribution patterns will be queried to identify any common geographic characteristics and religious motifs. For example, this project looks at the sites in the dindshenchas that specifically mention one obvious religious motif - the druids. The analysis might yield a patterned religious motif other than one as obvious as druid references, possibly establishing geographic criteria for identification of sacred sites (such as places particularly associated with water or high places with a minimal view range). Further querying ArcView about patterns of geographic characteristics could identify other sites possessing such particular geographic characteristics, producing a locational model for sites not yet recognized as sacred. The geographic sites thus identified would be compared with the locations of other sites among the 770 mentioned in the dindshenchas that lack the druid motif. A significant level of agreement would confirm the correlation between pre-Christian Ireland's religion and the landscape, thus demonstrating the historic significance of the data in the dindshenchas, and the essentially religious nature of those tales, whereas a low degree of correlation would refute that hypothesis.

The distribution patterns contain other information significant to archaeology that can be explored and delineated by GIS analysis. Information from the dindshenchas will be used in conjunction with GIS techniques to predict the most likely routes for the legendary Five Roads of Tara, site of the ancient Seat of Ireland's High Kings. The legendary Five Roads of Tara, described in the dindshenchas of Slige Dala, are named Slige Dala, Slige Assail, Slige Midluachra, Slige Cualann, and Slige Mor. General road routes are described in the dindshenchas, with mention of a few reference locations along each road. While researching the legendary Five Roads of Tara, three other roads, referred to hereafter as "cow" roads, were found in Lady Gregory's Irish Myths and Legends (Lady Gregory 1910). Lady Gregory relates the legend of how Manannan's three cows (one white, one red, and one black) created the first three roads in Ireland. These three routes are included in this project.

Esri's Data and Maps (Esri 1998 - 2001) provide a digital basemap for Ireland, including Northern Ireland. The project uses ArcView's Table, View, and Layout functions of ArcView 3.2a. The Table documents organize and coordinate tabular data from the dindshenchas by creating fields (i.e., columns) and records (i.e., rows) in which data are entered. The View function is used to display the basemap, the themes, and the manipulations (i.e., the GIS query results). The View function enables the creation of sets of geographic data, starting with a basemap. Tabular data is added to the View as thematic layers. Layout produces final maps.

This project creates thematic maps, unique to GIS programs. A thematic map contains several layers, each one representing a particular "theme." Themes are added to a View, creating a complete picture of the correlation between themes. Thematic layers added to the project View via the Add Event Theme tool are named: 1) Dindshenchas Sites, 2) druid sites, 3) relevant locations, and 4) known sacred sites. These four themes illustrate the geographic distribution patterns of the dindshenchas sites, the forty-six druid-related dindshenchas sites, the locations referenced to the projected Five Roads of Tara and the three "cow" roads, and the sixteen well-known prehistoric sacred sites. The final GIS procedure in this project will be the creation of several final map Layouts. Views of each theme and map components are added to separate Layouts to produce final maps; adding more than one theme to a layout produces layered thematic maps. The Layout component of ArcView combines cartographic techniques with the GIS thematic mapping capabilities to produce final layouts. The maps will test the idea that there is a distribution pattern correlation between the druid sites and known sacred sites, and that, given such a correlation, similarities and differences between the two site types can be analyzed. The analysis will produce the data for locational modeling of potentially significant sites, both along the projected road routes and throughout Ireland.

ArcView opens with a blank Project; the window allows the user to select the View, Table, Charts, Layout, Dialog or Script tools. Using the tools builds the project, and enables the user to organize, analyze and delineate whatever data is relevant to the project, thus creating an expandable database pertaining to the religious landscape of ancient Ireland, to which information can be added in the future. The basics of a basemap and x, y coordinates for the sites are the only two requisites; the possible correlations that one day may be made between the sites, agricultural phenomena, celestial orientation phenomena, various religious motifs, etc., are vast.

The first methodological objective is to create expandable database tables. The five database tables to be created using ArcView's Table function contain geographic and mythological information regarding five categories of information: 770 dindshenchas place-name sites, the 46 dindshenchas place-name sites that refer to druids or druidic lore, the 16 well-known prehistoric sacred sites data, 26 locations referenced in the literature as being associated with the projected Five Roads of Tara and the "cow" roads, and the projected road routes.

After creating the database, the question for the ArcView GIS program is: given the physical landscape of Ireland, map five routes for the Cow roads and to the Tara site starting at programmed terminal points 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8 and passing through known points on each route. The GIS will predict possible routes for the Cow roads and the Five Roads of Tara by using a cost analysis query procedure. The GIS-predicted routes may correlate with other dindshenchas sites that are not known to associate with the roads, or non-dindshenchas sites that are known to have prehistoric importance.

The dindshenchas sites database contains information that specifically relates to this project. The information includes geographic x, y coordinates, geographic "feature" site type (i.e., hill, rampart, stone enclosure, river, etc.), sacred motif type (i.e., water, stone, tree, mountain, bog/area, seaside/coast), hot-linked texts of the tales, names of significant characters in the tales (i.e., druids, kings, chiefs, deities, etc.), religious motifs, significant relationships (for example, between mythological characters, or between sites), county information, National Grid of Ireland zone data, male/female identification of significant druid characters, and the druid references in the dindshenchas. Other information, like celestial orientation data derived from the place-name sites, can be added to the database in the future, thus expanding the GIS database for further research regarding the dindshenchas and the Irish landscape.

The dindshenchas data illustrate sites reflecting many feature types. There are a variety of geographic feature types (identified by reviewing the dindshenchas and Foclóir Póca, an Irish/English dictionary): stones, rocks, heights, fords, passes, peaks, assemblies, cairns, enclosures, woods, pools, mounds, trees, provinces, bogs, palisades, estuaries, rivers, fairy mounds, mountains, roads, houses, ramparts, and swimming places (see Table 1).

Table 1: dindshenchas site feature types.

| Irish | English |

| adhlacadh (modern) | burial |

| ail | stone, rock |

| ard | height |

| ath | ford |

| belach | pass |

| benn, bend | peak |

| bile | tree |

| bri | hill |

| brug | palace, mansion |

| caisel | stone fort |

| carcar | prison |

| carn, cairn | cairn |

| carraic | rock |

| cenn | head, mountain |

| chaill | woods |

| cliath | hurdle |

| clocha, cloch | stone |

| cluain | meadow |

| cness | side of hill |

| cnoc | hill |

| coi | path, road |

| coire | cauldron |

| coirthe, coirthi | standing stone |

| crich | boundary, region, territory |

| cruachan | rounded hill |

| cuan | harbor, bend, curve |

| cuil | corner, nook |

| daire | oak wood |

| derc | grave |

| druim | ridge, hilltop |

| dubthir | thicket |

| duma | mound |

| dun | fort, fortress |

| iamh, fail (modern) | enclosure |

| fert | grave |

| fich | town land |

| fid | wooded |

| glais | stream, greensward |

| glen | glen, valley |

| gort | field of battle |

| grellach | clay |

| inber | estuary, river mouth |

| inis | island |

| lia | stone |

| lind | pool |

| loch | lake |

| luachair | rushes, reedy place |

| lecc | stone |

| mag | plain |

| moin | bog |

| mur | rampart |

| oenach | assembly |

| port | harbor |

| cuige (modern) | province |

| rath, raith | ringfort, rampart wall |

| rinnd | top, promontory point |

| ross | wood, headland |

| sce | slant, slope |

| sid | fairymound |

| sliab | mountain |

| slige | road |

| snam | swimming place |

| tighi | house |

| tir | country |

| tond | wave |

| tor | brush, shrub, tuft |

| tul, tulach | low hill |

| uaig | grave |

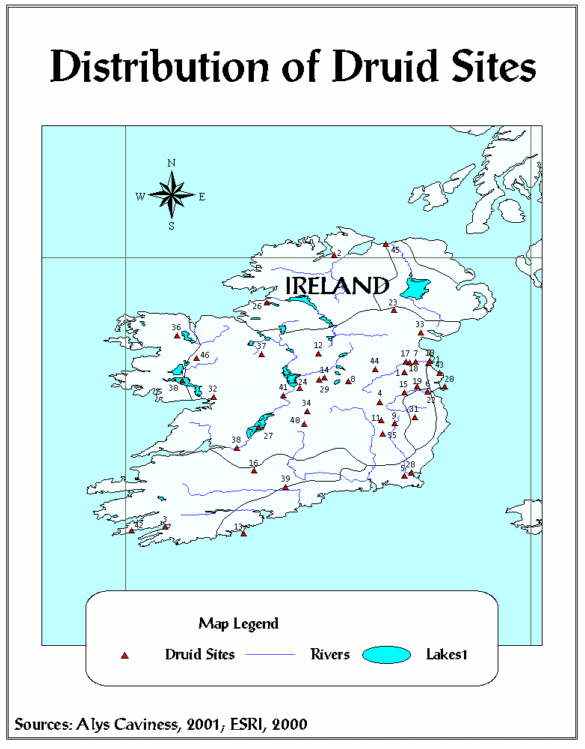

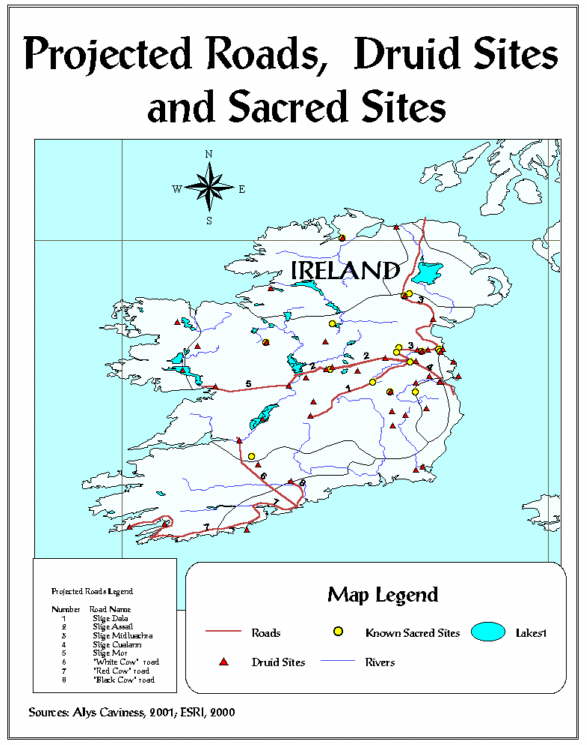

Map #1 shows the distribution of the 46 dindshenchas sites that are relevant to druids:

Table 2 delineates 46 druid-related sites by identification number, name, phonetic pronunciation, and feature type.

Table 2: The 46 dindshenchas druid sites.

| SITE | PHONETIC | TYPE | |

| 1 | Ailech | al-lek | ail, stone |

| 2 | Ailen Cobthaig | al-en cobhig | ail, rock, stone |

| 3 | Almu | al-eh-muh | cnoc, hill |

| 4 | Ard Lemnacht | ard lem-nect | ard, height |

| 5 | Ath Cliath Cualann | ah klea koola | ath, ford |

| 6 | Ath Grencha | ah grenna | ath, ford |

| 7 | Athais Mide | ah-hus meev | cnoc, hill |

| 8 | Belach Conglais | bela konglaze | belach, pass |

| 9 | Carman | car-mun | oenach, assembly |

| 10 | Carn Furbaide | karn ferbayduh | carn, cairn |

| 11 | Carn Hui Neit | karn wee net | carn, cairn |

| 12 | Carn Mail | karn mall | carn, cairn |

| 13 | Ceilbe | kel-buh | cnoc, hill; rath, enclosure |

| 14 | Cenn Febrat | can feh-raht | cenn, head; sliab, mountain |

| 15 | Cleitech | kleh-tux | burial |

| 16 | Cnogba | knock-uh | cnoc, hill |

| 17 | Cnucha | knuck-uh | cnoc, hill |

| 18 | Codal | ko-dahl | cnoc, hill |

| 19 | Dubad | doo-behd | cnoc, hill |

| 20 | Duma na nDruad | dooma na droud | duma, mound, hill |

| 21 | Duiblind | dub-lin | lind, pool |

| 22 | Emain Macha | owen mahkah | royal enclosure |

| 23 | Irarus | air-r-us | bile, tree |

| 24 | Laigin | lay-gihn | province |

| 25 | Loch Ce | lox key | loch, lake |

| 26 | Loch Dergderc | lox der-derk | loch, lake |

| 27 | Loch Garman | lox gar-muhn | loch, lake |

| 28 | Loch Lugborta | lox lug-borhuh | loch, lake |

| 29 | Loch nOirbsen | lox orvsin | loch, lake |

| 30 | Mag Breg | mah bray | mag, plain |

| 31 | Mag Mucraime | mah muk-kraym | mag, plain |

| 32 | Mag Muirthemne | mah mir-huhmnuh | mag, plain |

| 33 | Mide | meev | province |

| 34 | Moin Gai Glas | mohn ga glas | moin, bog |

| 35 | Nemthend | nev-hehn | sliab, mountain |

| 36 | Rath Cruachan | rah kruh-xuhn | rath, palisade, wall |

| 37 | Sid Nechtain | sid nax-un | fairymound |

| 38 | Sinann | shannon | inber, river |

| 39 | Sliab Cua | shleev koo-uh | sliab, mountain |

| 40 | Slige Dala | slee dahl-uh | slige, road |

| 41 | Snam Da En | snav da ehn | snam, swimming place |

| 42 | Tech Duinn | tex dun | tighi, house |

| 43 | Temair | taur (tara) | mur, rampart |

| 44 | Tlachtga | tlax-uh | cnoc, hill |

| 45 | Tuag Inber | too-ah in-ver | inber, river |

| 46 | Umall | oo-mall | mag, plain |

The dindshenchas place-name sites that mention druids contain the following feature characteristics: 4 stone sites; 15 hills, cairns, or mounds; 2 fords; 1 (mountain) pass; 4 mountain peaks; 1 assembly place; 1 burial place; 2 wooded or tree sites; 9 rivers, lakes or pools; 3 enclosures; 2 provinces; 4 plains; 1 bog area; 1 road reference; and 2 house sites. Some sites have more than one feature type characteristic; for example, the Tara sites (i.e., Temair, Rath na Rig, Clocha) exhibit feature characteristics of hill, rath (ringfort), burial, and stone. Of the sites that mention druids, the most common site types are hills, mountains, plains, and lakes.

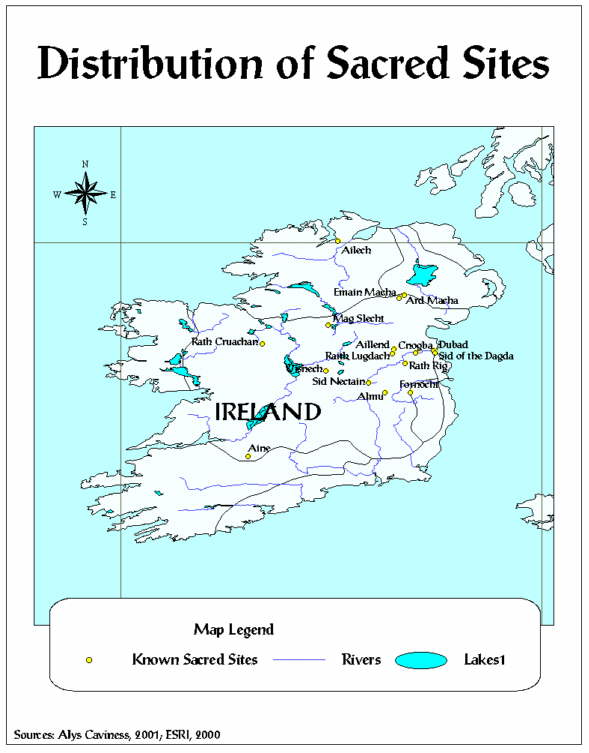

Map #2 illustrates the distribution of the 16 well-known sacred sites:

Table 3 shows the 16 well-known prehistoric sacred sites and feature type.

Table 3: The 16 well-known prehistoric sacred sites.

| ID | SITE | FEATURE TYPE |

| 1 | Ailech | stone, hill |

| 2 | Aine | stone, hill |

| 3 | Aillend | hill |

| 4 | Almu | hill |

| 5 | Ard Macha | hill |

| 6 | Sid Nectain | hill, mountain |

| 7 | Brug na Boinde | hill |

| 8 | Cnogba | pass |

| 9 | Dubad | pass |

| 10 | Emain Macha | hill & enclosure |

| 11 | Fornocht | stone & enclosure |

| 12 | Mag Slecht | plain |

| 13 | Uisnech | hill, ring fort |

| 14 | Rath Cruachan | hill, ring fort |

| 15 | Raith Lugdach | hill |

| 16 | Rath Rig | hill, enclosure, burial |

The project data entered in the Known Sacred sites table include a site identification number, site name, dindshenchas number, dindshenchas title, geographic location description, longitude and latitude coordinates, site feature type, county identification, druid reference, and Irish National Grid Coordinates. These sites have been regarded as sacred throughout the recorded history in Ireland and are mentioned in the dindshenchas and other literature associated with the origin of the place-name sites. The 16 well-known prehistoric sacred sites consist of 2 stone sites, 15 hill sites, and 3 area sites. As with the druid sites, some sites have more than one feature type. Of the sixteen well-known prehistoric sacred sites, ten sites have druid references in the myths and legends associated with them.

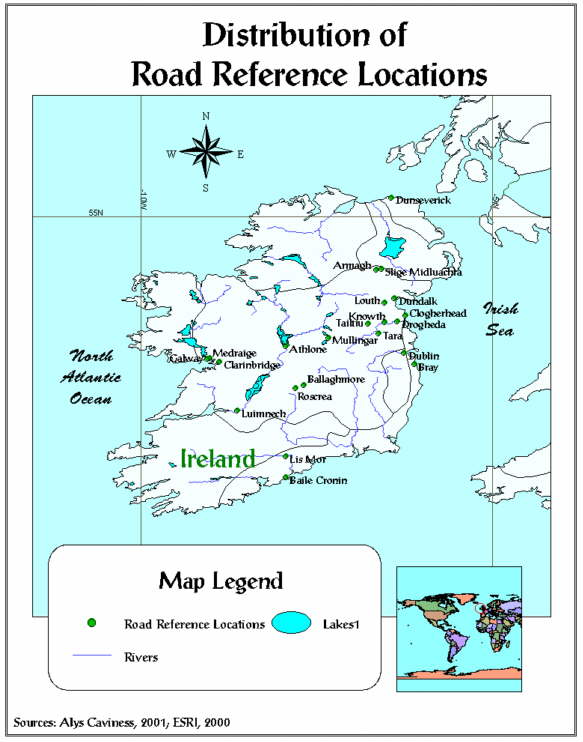

Map #3 shows the distribution of the road reference location data:

The road reference location data is compiled from various sources, starting with the dindshenchas that specifically mention the Five Roads of Tara and the three "cow" roads in Lady Gregory's Irish Myths and Legends. A careful review of the literature reveals other sites that associated with the road routes, and these locations are included in the tabular data. An identification number, the location name, geographic location description, and longitude and latitude coordinate points are included in the database. These sites are identified as modern cities or towns, and will be used in ArcView to aid in projecting the roads. There are not many data concerning feature type for these sites, although some can be identified with a sacred motif like water or mountain areas. However, the reference locations will not be analyzed in terms of feature type, as will the druid sites and the 16 well-known sacred sites.

GIS allows the theme distributions to be viewed simultaneously, thus showing correlation between the themes. Queries can then be made between one or more themes to select sites that are in close geographic location or that share some other characteristic. For example, the Query Builder tool can find features that are near or adjacent to other features, in one theme or between themes. Using the Query Builder will enable the identification of druid sites and well-known sacred sites that are in close proximity to each other, and allow for a cost analysis query to identify the projected routes for the Five Roads of Tara and the "cow" roads. The cost analysis requires querying the terminal points (i.e., Temair and Dunseverick for the road named Slige Midluachra) and any reference locations for each legendary road. ArcView uses that information in conjunction with the terrain of Ireland to project the road routes.

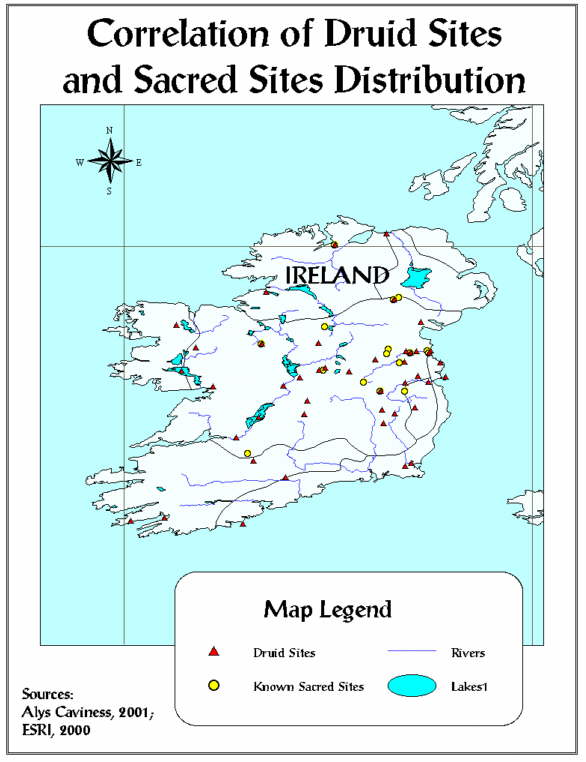

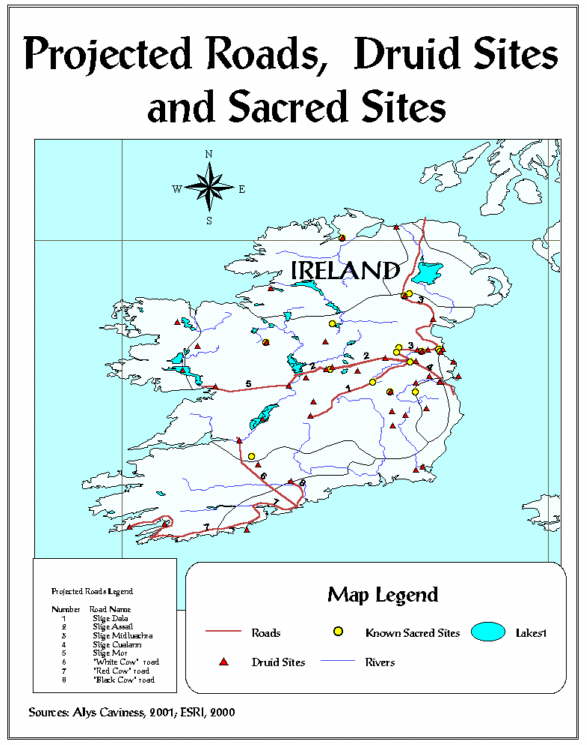

Map #4 illustrates activating the druid sites and the well-known sacred sites themes, resulting in a high degree of correlation between the two geographic distribution patterns:

Eleven druid sites and nine of the sacred sites are the same geographically. The most populous areas for both site types are along the Rivers Liffey and Boyne. The correlation between the druid sites and the well-known prehistoric sacred sites suggest two interesting attributes. The first is that hill sites are the most common sacred site feature type (although Cnogba and Dubad are man-made mounds rather than natural hill formations). The second attribute is that 10 of the 16 well-known sacred sites directly correspond with 11 dindshenchas that specifically relate legends regarding druids. The Irish words for hill and druid are druim and druid, respectively. This etymological relation supports the supposition expressed that mythological data and the geographic landscape express cultural reality.

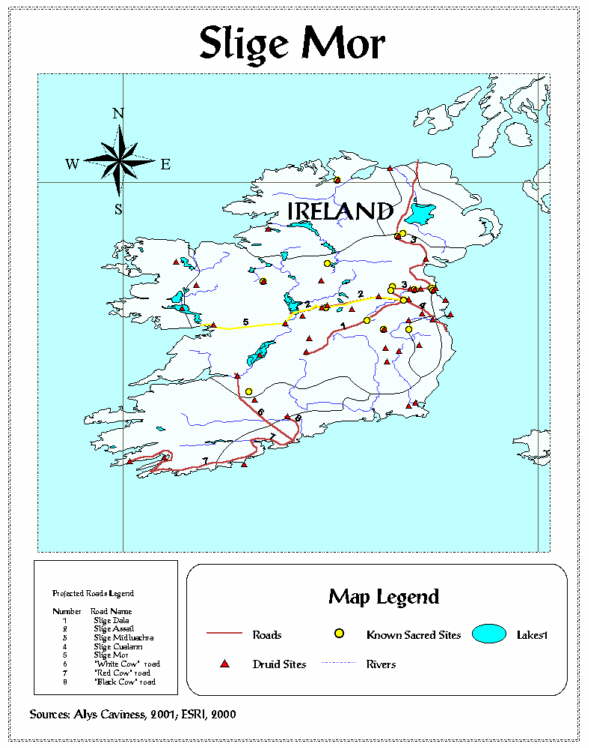

ArcView successfully performed a cost-analysis query to project road routes based on the data from the mythological sources. Map #5 shows the projected road routes, White Cow road, Red Cow road, Black Cow road, Slige Dala, Slige Assail, Slige Midluachra, Slige Cualann, and Slige Mor:

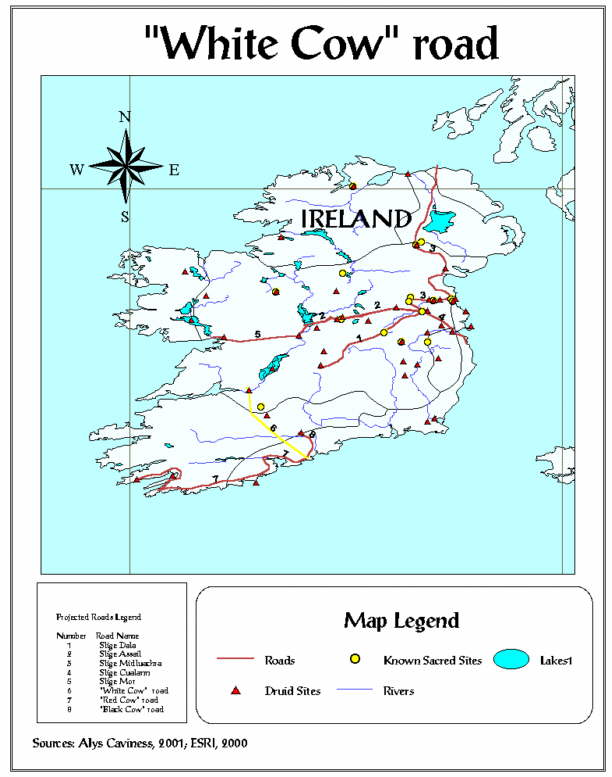

The road numbered 6 is the White Cow road. Manannan's white cow came out of the sea at Baile Cronin (near Ballymacoda) on the south east coast of Ireland and traveled inland approximately one mile. From that point, the white cow turned northwestward, and made its way to Luimnech (Limerick). Map #6 shows White Cow road highlighted in yellow:

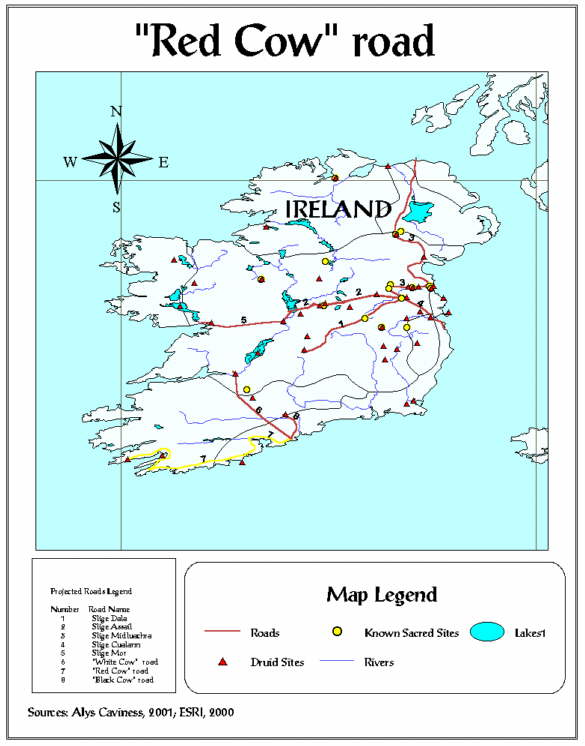

The road numbered 7 is the Red Cow road. Manannan's second cow, a red one, came out of the sea with the other two and also traveled with them approximately one mile inland from Baile Cronin. There, the red cow separated from the other two and turned to the southwest and journeyed towards Dursey Island along the southwestern coast of Ireland. Map #7 shows Red Cow road highlighted in yellow:

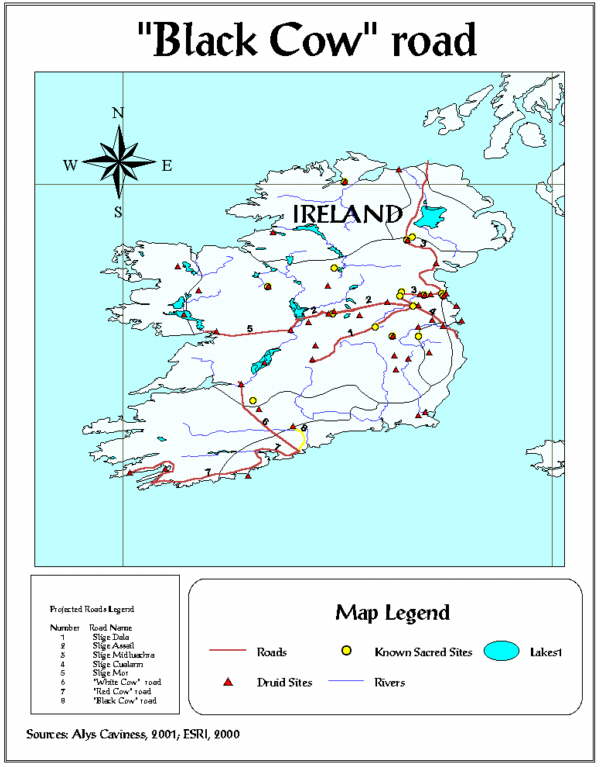

The road numbered 8 is the Black Cow road. Manannan's third cow, which was black, emerged from the sea with the other two cows and traveled inland about one mile with them. There, the three cows parted ways, and the black cow turned to the northeast and walked towards Lis-Mor (Lismore). Map #8 shows Black Cow road highlighted in yellow:

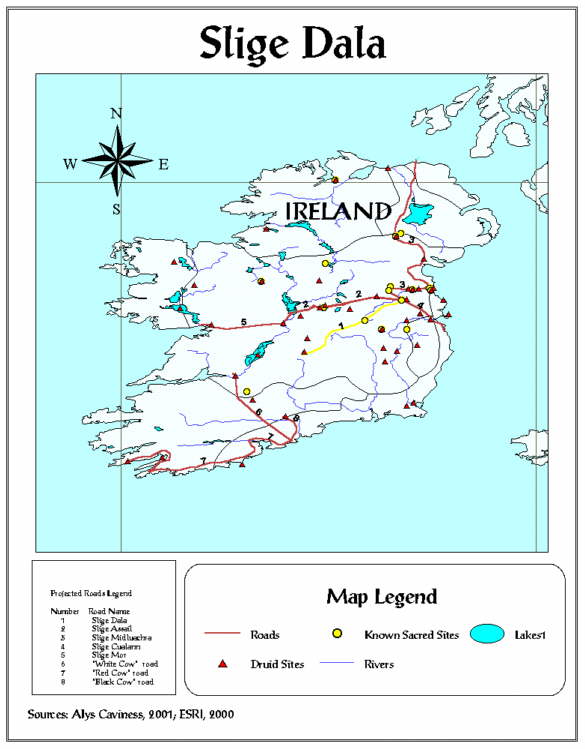

Slige Dala was known as the Great Southwestern Road. It extended from the southwestern side of Temair (Tara) into Ossory to Roscrea (see Map #9). The road is described as passing by the castle of Belach Mor, near Mag Lena (Moylen) and near Borris-in-Ossory. Map #9 shows Slige Dala highlighted in yellow:

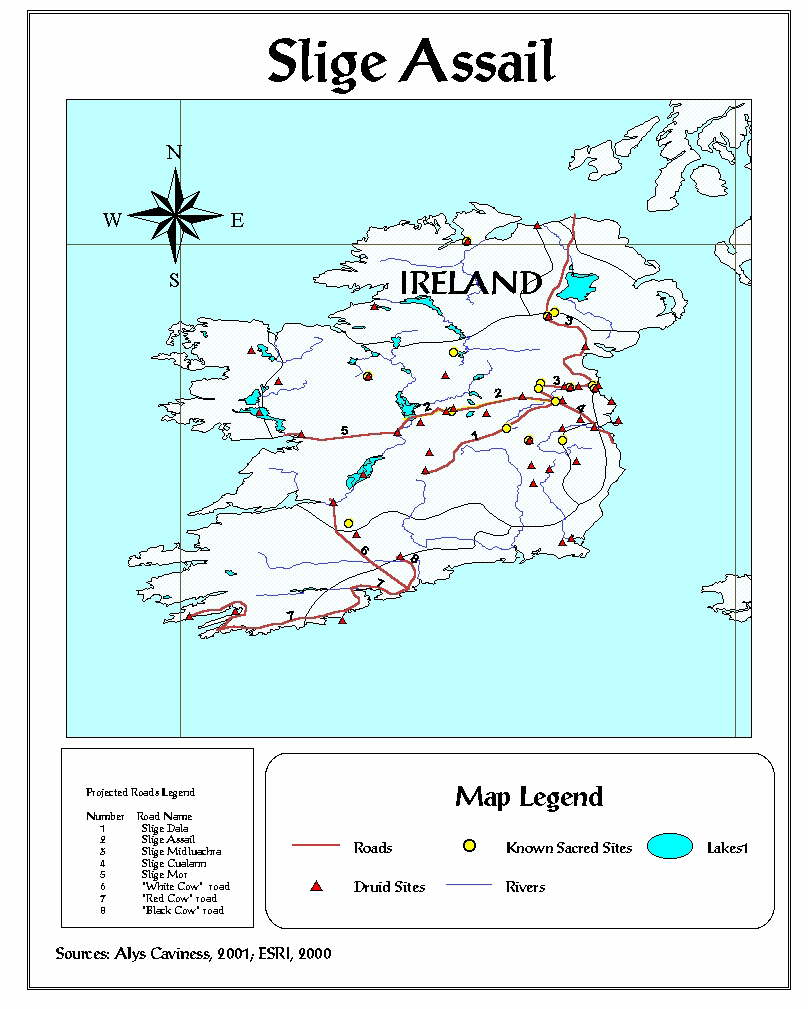

This is the western road that extends from Temair (Tara) toward Loch Owel near Mullingar. Slige Assail delineated the division between North and South Mide (Meath). Map #10 shows Slige Assail highlighted in yellow:

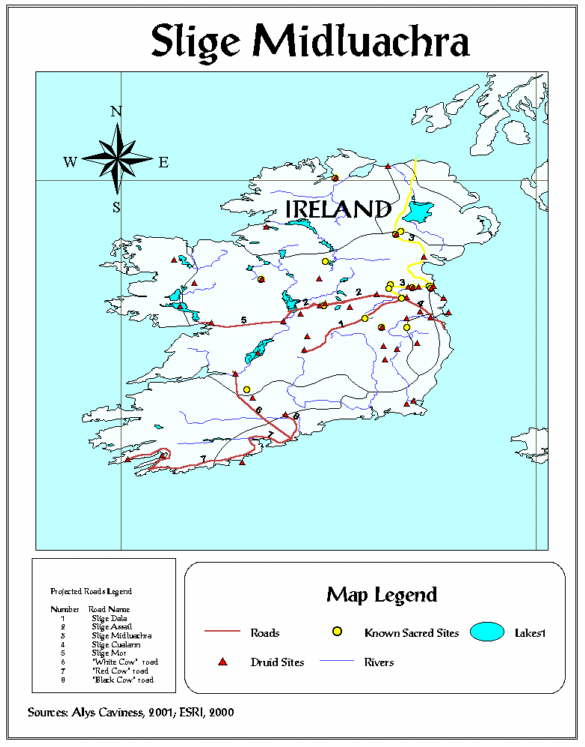

Slige Midluachra is the northern road that extended from Temair (Tara) through Emain Macha and on to Dunseverick (in present-day Northern Ireland). It is described in the literature as passing on or near Drogheda, Dundalk, Sliab Fuaid, Moyra Pass, Cell na Sagart (Kilnesagart), Druim Cain (in Louth), Clogher (north of Dundalk), and Loch Trena (some of these locations are in the dindshenchas database). Slige Cualann met Slige Midluachra at Tara; the two roads are extensions of one another. Map #11 shows Slige Midluachra highlighted in yellow:

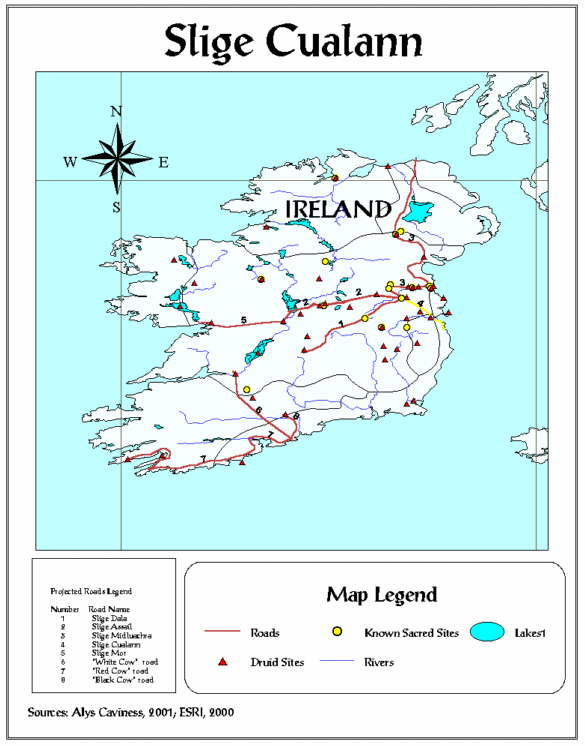

Map #12 shows this road highlighted yellow; a southern extension of Slige Midluachra, described in the literature as extending from Temair (Tara) to Bray, through Brywn and Bohrynbrynee near Glashymoky to Dublin:

This is the "Great Western Road," the lie of which is defined by the Escir Riada (gravel hills extending from Dublin to Galway). Slige Mor is a further extension westward of Slige Assail. The road runs along Slige Assail to Mullingar and then continues westward through Clarinbridge, Medraige, and Galway. Map #13 shows the projected road route highlighted in yellow:

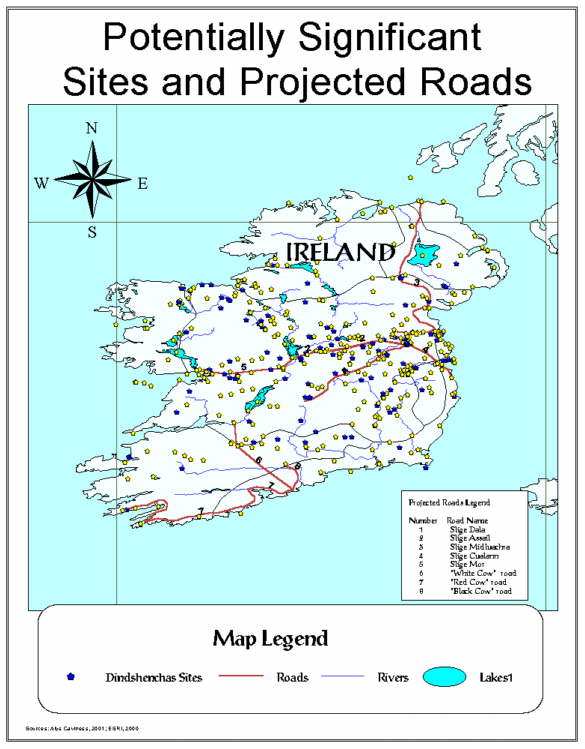

Many of the druid sites and well-known known prehistoric sacred sites that are mapped in this project correlate to the eight projected road routes, as seen on see Map #5:

Twenty-one sites correlate geographically with one or another of the projected routes for the Five Roads of Tara. These sites are: Duma na nDruad (Achall), Athais Mide, Carn Mail, Irarus, Tlachtga, Emain Macha, Mag Muirthemne, Ath Grencha, Duiblind, Mag Breg, Cnucha, Mag Mucraime, Cleitech, Cnogba, Dubad, Brug na Boinde, Loch Lugborta, Uisnech, Sid Nectain (Boand), Temair, and Rath Rig. The sites are predominantly hill sites, with some of the sites exhibiting association to water-related sites as well. All but two sites, Almu and Carman, are on or near one or another of the projected road routes discussed in this project. Until the projected road routes are investigated in the field (not attempted in this project), it cannot be said with certainty that these sites are significant to the history of the roads themselves. However, the clear geographic correlation made in this project between the projected road routes and some of the druid sites and well-known prehistoric sacred sites is strong.

It is possible that sites found on or near the routes had religious significance to the ancient Irish Celts as they traveled to and from Tara for religious, political or social events. Performing particular ceremonies or making ritual offerings at each sacred site (relevant to the particular ceremony or ritual) along the way could have made journey became something of a religious pilgrimage. This project uses a cognitive approach to understanding the relationship between the geographic landscape of ancient Ireland and the dindshenchas mythology of the ancient Irish Celts, and proves that hill sites in particular were perceived by the ancient Irish Celts as important in religious and power-related ways. It is clear that the mapping of the projected Five Roads of Tara illustrates the importance of examining the connection between ancient Irish mythology and the geographic landscape.

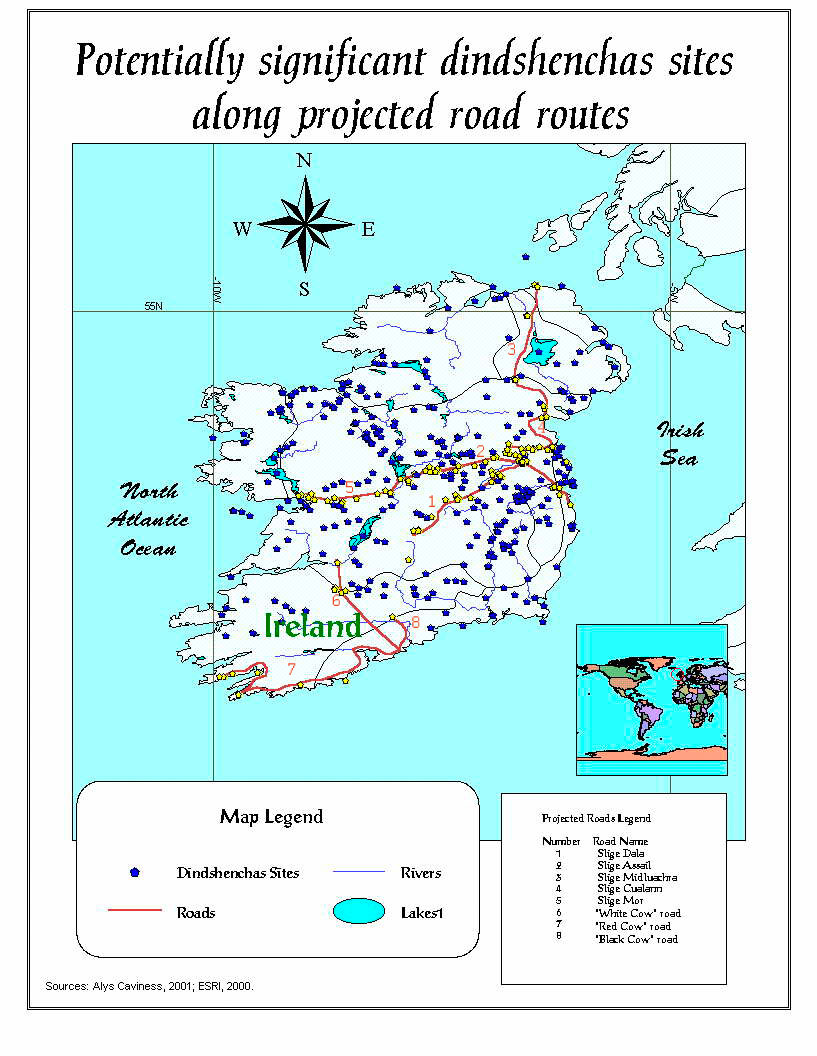

Mapping the distribution of the dindshenchas sites with the projected road routes shows that 207 of the sites are along the routes (see Map #14; these 207 sites are highlighted in yellow). The method used to make the selection is as follows: The dindshenchas theme in the project View is made Active; the Select By Theme tool opens a dialog box; pull down menus select features of the active dindshenchas theme that Intersect with the roads theme. These 207 sites are predominantly hill, mound, or sites near water.

What one notices in the distribution of the dindshenchas sites is not only the clusters along known roads that are discussed in this project but also other linear groupings suggesting the existence of roads not mentioned in the early literature. There seem to be three particularly obvious groupings, the first from the area along the River Liffey in County Kildare toward and along the River Barrow to the south, the second from near Athlone toward Sligo to the northwest, and the third extending north-south from Galway toward Killala Bay in County Mayo. These interesting road-like linear groupings could be further explored, using the theories and methods applied in this project.

Examining the dindshenchas in their entirety gives a clearer picture of the cognitive landscape of ancient Ireland. Of the approximately 770 sites in the dindshenchas, this project's locational modeling has identified 424 sites as potentially significant based on feature characteristic similar to the druid sites and well-known prehistoric sacred sites identified in this project - sites that are hills, mounds, or near water. Map #15 illustrates this locational modeling:

There are 217 hill or mound sites in the distribution of 424 potentially significant sites, and 163 of the sites are on or near some type of water: bog, pool, river, lake, or sea. (The 217 hills or mound sites do not include any man-made rath or fort sites that may be on hills or mounds.) As with the druid sites and well-known prehistoric sacred sites, it is important to remember that many sites have more than one feature characteristic. Also, it is important to note that quite a lot of the sites in the dindshenchas share the same geographic location - for example, there are fifty-two different dindshenchas place-name sites located at Temair (Tara), and twenty-three place-name sites located at Tailtiu (Teltown). In other words, sites from different dindshenchas reflect the place-name legends of particular features or parts of Temair (Tara) or Tailtiu (Teltown). Sites at Temair (Tara), Tailtiu (Teltown), and Brug na Boinde (the Bend of the Boyne) are the most common overlapping geographic locations, but there are many others as well. ArcView does create a map symbol for each site regardless of duplicate geographic location, but that is not clear on maps. The site symbol for the last-listed duplicate location in a table is the one visible on a map. Using the Identify tool on that one site produces a pop-up table that lists all sites at that location.

Despite the initial confusion of this geographic overlap, when one looks closely at the dindshenchas and understands the importance of each particular aspect of the detailed descriptions of the sites, it becomes clear that the ancient Irish Celts associated great significance to every detail of their landscape and the features represented at the place-name sites. Thus, features that are, in geographic reality, practically on top of one another still retain their individual significance.

Anthropology seeks to understand the motivation behind the traditional beliefs and practices in studies of various cultures, but this approach is usually limited to ethnographic studies of extant cultures - the primary methodology of cultural anthropologists. The application of a cognitive theory is not as widespread in archaeology as it is in cultural anthropology. This project illustrates that the traditions and mythologies, either written or oral, of any culture can be used as legitimate sources of archaeological data concerning the past, using the methods and theories applied here to reveal otherwise hidden cultural patterns. Archaeologists study the material artifacts of a culture. In this case, the ancient culture's artifacts are the land itself. The project suggests that, in the mind of the ancient Celt, the "sacred object" was often a geographic feature itself - a hill, or a stone, or a river or lake, rather than something made or marked by humans.

This research is of potential importance in three ways. First, the analysis of the correlation between the mythological data found in the dindshenchas and the patterned geographical features provides insight into pre-Christian Ireland's religion and its correlation to Ireland's landscape. An analysis of the dindshenchas shows that the most significant geographic features were hills and water bodies. The correlation supports the theory that the dindshenchas can be used as a legitimate source for information about ancient Irish Celtic religious beliefs. One can postulate that the people of ancient Ireland identified hill and mound sites with the sky and water sites with life. Within the dindshenchas, 424 potentially significant sites described with these features are identified, with 207 of those sites being on or near the projected road routes. Hill sites are identified in this project as the most common and significant geographic feature of the religious landscape.

Second, the GIS-predicted projected road routes provide archaeological data that can be tested in the field; mapping the possible routes for the Five Roads of Tara and the three cow roads provides likely places to seek tangible evidence for the roads. Further archaeological investigations could be undertaken, including remote sensing, on-site surveying, and excavation of the routes mapped in this project, which might one day yield the real-world discovery of the Five Roads leading to Tara. This GIS project can offer future researchers the opportunity to examine the correlations suggested in the mapping of the projected road routes, including motifs or features of the Irish landscape like celestial orientation information or slope aspect. The methodology can be applied to such motifs and features, thus expanding the scope of investigation beyond that of the druid motif.

Third, the project illustrates the significance of using both mythology and GIS in archaeological research. Using ArcView to map the projected roads described in the literature and identify the sites in the dindshenchas that may be important in relation to them provides a significant achievement in synthesizing mythology and non-intrusive tools of investigation. It is clear that the synthesis of GIS and an unconventional archaeological source like mythology is a successful method for organizing, analyzing, and interpreting mythological and geographical data.

This project demonstrates a synthesis of cultural anthropological and archaeological theory and method with the use of mythology as a historic source and GIS as non-intrusive tools, producing a significant technique for applying archaeological research to cultures both extinct and extant. The dindshenchas are historical records of deeply held ancient religious and cultural beliefs, and can be legitimately used as such. GIS proves to be valuable in the organization and analysis of mythological and geographic data. The availability of GIS programs for PCs makes their applicability as non-intrusive archaeological tools more convenient. Software innovations, like Esri's ArcView Spatial Analyst Extension program, make the future of GIS in archaeological research even more exciting.

Cognitive archaeological studies using GIS would encourage the establishment of specific continuity between past and contemporary cultural beliefs. Synthesizing mythological data and geographic data assists in researching culture over time. The successful expression of cultural continuity evident herein suggests that cultural continuity can be traced by something other than material cultural artifacts; namely, mythological information. Today's archaeologists must be able to understand cultural continuity over great periods of time whether or not the material archaeological record is complete. The success of using a cognitive approach to interpreting culture is demonstrated by the delineation of the ancient Celtic association of hills (druim) to druids (drui). One can enter the mind of an ancient Irish Celt looking out onto the Irish landscape, easily imagining that Celt, perhaps a druid, seeing the hills of Ireland touching the sky and identifying them as the most sacred geographic feature of the landscape. One can imagine a Celtic family, journeying on a worn path to a festival at Tara, pausing along the way to pay homage to their gods at a sacred hill site shrouded in mist. Thus a connection between the physical landscape and the religious landscape may have been born, and evidence of that connection still exists in the dindshenchas and their geographic realities.

The methodological and theoretical ideas employed in this thesis 1) provide an alternative approach to doing archaeological investigation, and 2) collapse the division between archaeology and cultural phenomena like mythology. Establishing ties between native mythologies and geographical realities demonstrates cultural continuity, as this project establishes cultural continuity between pre-Christian Ireland's mythology and contemporary geographic features. The continuity of Irish religion, from the mists of prehistory to the present day, is traced via the sites referenced in the dindshenchas. Elements of the traditions and mythologies of cultures from the past are often preserved over time in ways that modern people either take for granted or do not even notice. The continuity evidenced by the dindshenchas as they correspond to contemporary locations is good evidence that many such traditions and mythologies - preserved orally or in historical documents - should be taken seriously by anthropologists and archaeologists as legitimate sources of cultural information.

This alternative approach can be applied to research documenting cultural continuity, particularly with relevance to contemporary legal and ethical controversies. For example, there are issues raised in legal cases in United States that involve human remains or native Indian land claims and beliefs. The status of "mythology" is not high in non-academic settings like the U.S. District Courts that are hearing cases involving human remains or native land claims. Although oral tradition is one of the elements to be considered in repatriation and protection cases, the Courts often look for documentation that proves cultural continuity between contemporary Native American groups and the past. Most native mythological traditions are not documented as anything other than mythological legends, similar to the dindshenchas. The methods used in this project could establish ties between native Indian legends and the physical landscape of North America, thus establishing documented cultural continuity.

The synthesis of cultural anthropology and archaeology is a methodology that can and hopefully will be examined as an effective way to overcome traditional tensions between the subfields of anthropology. Such changes in anthropology's dynamics, or perspective, seem to be inevitable. Anthropology, like its subject matter, is in a constant state of change, and how anthropologists choose to deal with change is always under discussion in the discipline. This project demonstrates a methodology that is relevant to that discussion.

Despite inevitable change over time, anthropology provides humanity with continuity. In the ancient Mayan city of Chichén Itza, for example, one can walk along a path leading to the Cenote of Sacrifice, a natural pool of water into which sacrificial victims were thrown in order to placate Kukulcan, the Feathered Serpent God. One connects with the past there - almost hearing 1,200-year-old screams of terror. The Umatilla Indians feel directly connected to the 9,000-year-old bones of Kennewick Man. People who have seen the Great Pyramids of Egypt, or the anthropoid footprints at Laetoli, have felt similar connections to the past. Through physical anthropology, cultural anthropology, archaeology, and linguistics, the discipline of anthropology crosses all borders of time and space. By studying extant and extinct cultures, anthropology establishes continuity to the past and the future, giving more than an emotional glimpse into other worlds.

Anthropology brings the past alive, and presents the possibilities for the future. The persons who created the Pyramids, the Temple of Kukulcan, and the dindshenchas did so with the future in mind; humans want to be more than a brief blip in time. Establishing connections to the past and the future gives the illusion of immortality. The people who produced pre-Christian Ireland's Celtic worldview of heroes, gods, and belief systems, and named Ireland's landscape features accordingly continue to exist and are connected to modern people by projects like this one. One hundred years from now, someone will connect to data and research being produced today, continuing the cycle of connection. Anthropology is a way to experience what it means to be human - to study what we as the human species have created as our world and to recognize our own connection to the past and the future by developing our knowledge in the present.

I would like to acknowledge and thank the following organizations and people for their help, encouragement, and support: Ball State University Anthropology Department; Ball State University Geography Department; Ball State University Graduate School; The Ball State Women's Club; Dr. Ron Hicks, Dr. Larry Nesper, Dr. Don Merten, Dr. John T Dorwin, and Mr. Paul Shanayda.

1. TEMAIR *S.20. drai, translated as "wizard," referring to Lucat Moel, King Loeguire's wizard. *S.21 dru[id]ib, translated as "wizards," referring to three wizards named Moel, Blocc, and Bluicne and the three stones set over them after their deaths.

7. MIDE drai[d]e, translated as "wizards," referring to the wizards of Ireland. druid, translated as "wizards," referring to the wizards of Ireland. prim drai, translated as "wizard," referring to Mide, chief wizard and chief historian of Ireland.

9. LAIGIN drai[d], translated as "wizards," referring to Ireland's wizards (singing spells on the Galeoin).

14. MOIN GAI GLAISS draidecht, translated as "magic" (or "druid lore"), referring to a lance made by anonymous smith.

18. CARMAN drai[d]ib, translated as "wizards," referring to the Tuatha de Danann, specifically Lugh Laebach.

26. DUIBLIND ba drai & ba banfile, translated as "a druid and poetess," referring to Dub, daughter of Rodub, son of Cass, son of Glas Gamna.

35. BELACH CONGLAIS druidecht, translated as "wizardry" (in footnotes, druidechta is translated as "by magic"); referring to Lomna, son of Donn Desa.

39. ARD LEMNACHTA drai, translated as "druid," referring to Trostan, a Pictish Druid.

40. LOCH GARMAN drui, translated as "wizard," referring to Bri, son of Baircid.

46. CARN HUI NEIT drúad, translated as "wizard," referring to Findgoll, son of Findamnas.

58. SLIGE DALA ndrui[d]ib, translated as "warlocks," referring to the warlocks of Ormond.

70. MAG MUCRAIME drúidechta, translated as "magical," referring to swine that came to Ailill and Medb from the Cave of Cruachu.

83. NEMTHENN bandrúi, translated as "druidess," referring to Dreco, daughter of Calcmael, son of Cartan, son of Connath.

88. CARN FURBAID drúi, translated as "wizard," referring to the wizard of Ethne, Furbaide's mother, daughter of Eochaid Feidlech and wife of Conchobar mac Nessa.

110. TLACHTGA druidechta, translated as "magic," referring to Tlachtga, daughter of Mog Ruith, learning the "world's magic." druadh, translated as "Magus," referring to Simon.

111. MAG BREG drai, translated as "a wizard," referring to Cleitech, a wizard of the Tuatha de Danann.

117. HIRARUS (IRARUS) druid, translated as "wizard," referring to Bicne, Cairbre's wizard. drui, translated as "wizard," referring to Bicne.

141. TUAG INBIR drai, translated as "druid," referring to Fer Fidail, son of Eogobal, who was a pupil of Manannan's and a druid of the Tuatha de Danann. drai, translated as "druid," referring to Fer Fidail.

159. LOCH N-OIRBSEN drui, translated as "druid," referring to Mananann, who was killed at the Battle of Cuillui. Mananann was also known by the names Gaer, Gaeal, and Oirbsen. banfili & bandrui, translated as "poetess and druidess," referring to Brigit, daughter of Eochaid Ollathar.

161. EMAIN MACHA ndruid, translated as "druids," referring to the seven druids that were one-third of the surety given for three kings to reign, in a revolving kingship, for seven years each at a time. ndruid, translated as "druids," same reference.

References to druids in The Metrical Dindshenchas:

PART ONE

TEMAIR II Line 36: drúthi, translated as "druids," referring to Druids seeing the House of Tephi.

TEMAIR III Line 178: druithib, translated as "druids."

ACHALL Line 13: [Duma na] nDrúad, translated as "the Mound of the Druids," referring to the mounds at Temair in a descriptive passage. Line 29: [Duma na] nDrúad, same translation and reference as above.

PART TWO

MIDE Line 26: drúide hÉrend, translated as "druids of Erin." Line 30: drúide hÉrend, translated as "druids of Erin." Line 32: ndrúad [ndron-ard], translated as "strong and noble druids." Line 40: prím-drúi, translated as "chief druid," referring to Gaine, daughter of Gumor.

ALMU I Line 13: drúi, translated as "druid," referring to Nuada the druid. Line 22: drúi, translated as "druid," referring to Tadc, son of Nuada.

PART THREE

BOAND II Line 45: drúad, translated as "the druid's," referring to Nechtain mac Namat.

CNOGBA Line 66: drúidecht, translated as "druid spell."

CEILBE Line 91: drái, translated as "druid," referring to Dallan son of Machadan. Line 94: drái, translated as "druid," referring to Dallan.

DUIBLIND Line 5: ba drui, (druidess) translated as "wizard," referring to Dub daughter of Rodub.

ATH CLIATH CUALANN Line 7: drúi, translated as "seer."

BELACH CONGLAIS Line 8: drúidechta, translated as "wizardry."

ARD LEMNACHT Line 21: drúi, translated as "druid," referring to Drostan son of Gelon.

LOCH GARMAN Line 145: drúi, translated as "druid," referring to Bri son of Bairchid. Line 149: drúi, same. Line 157: drúi, same. Line 171: drúi, same.

CEND FEBRAT Line 67: ndrúad, translated as "druids."

SLIGE DALA Line 80: drúid Irmuman, translated as "druids of Irmumu."

SINANN II Line 16: dráidechta, translated as "wizardry."

LOCH DERGDERC Line 42: drúi, translated as "druid."

RATH CRUACHAN Line 69: drúi, translated as "druid."

MAG MUCRIME Line 14: drúidechta, translated as "magical."

LOCH CE Line 8: drái, translated as "druid," referring to Ce son of Echtach. Line 13: drái, translated as "druid," referring to Ce. Line 31: drái, translated as "druid," referring to Ce.

PART FOUR

NEMTHEND Line 4: drui, translated as "wizard," referring to Dreco daughter of Calcmael.

TUAG INBER Line 28: druí, translated as "druid," referring to Fer Fi. Line 29: druí, translated as "druid." Line 33: druí, translated as "druid." Line 38: druí, translated as "druid." Line 49: drúad, translated as "druid."

ATH NGRENCHA Line 14: druíde, translated as "druids."

AILECH III Line 64: draí, translated as "druid."

CARN MAIL Line 136: druí, translated as "seer," referring to Lugaid Mac Con.

MAG BREG Line 21: druí, translated as "druid," referring to Tulchinde.

CLEITECH Line 1: druí, translated as "druid," referring to Cleitech.

IRARUS Line 30: druíd, translated as "druid," referring to Bicne. Line 33: druí, translated as "druid." Line 49: druí, translated as "druid." Line 55: druí, translated as "druid." Line 62: druí, translated as "druid." Line 70: druí, translated as "druid."

CNUCHA II Line 5: Fert in Drúad, translated as "Fert in Druad," referring to the ancient name of the hill Cnucha, literally "grave of the druid."

PROSE DINDSHENCHAS IN THE METRICAL DINDSHENCHAS PART IV:

CODAL *draidh, translated as "druid," referring to Aed's druid.

DUBAD *draidechta, translated as "magic." *draighecht, translated as "magic."

UMALL *druídhecht, translated as "magic."

LOCH LUGBORTA *druidhechta, translated as "magic."

MAG MUIRTHEMNE *draidhechta, translated as "magic." *ndruidhechta, translated as "magic."

ATHAIS MIDE *druí, translated as "druid."

AILEN COBTHAIG *Druí, translated as "druid," referring to Dinel the Druid. Line 30: druí, translated as "druid," referring to Dinel.

TECH DUINN *ndruí, translated as "druid." *ndrúadh, translated as "druids."

METRICAL DINDSHENCHAS IN PART IV:

SLIAB CUA Line 9: drui, translated as "druid," referring to Buadach mac Birchlui. Line 16: druád, same as above. Line 17: drúi, same as above.

SNAM DA EN (in both prose and metrical versions) *drúidh, translated as "druid," referring to Nar's druid. *drái, translated as "druid," referring to Nar's druid. Line 26: druid, translated as "druid," referring to Nar's druid. Line 29: drúi, translated as "druid," referring to Nar's druid.

An Gum, Brainse na bhFoilseachan (The Plan, Branch of Publication), Foclóir Póca English-Irish/Irish-English Dictionary. An Cuigiu Clo (fifth edition), Baile Atha Cliath: Criterion Press, 1993.

Caviness, Alys, An Examination of the Concept of Druid(s) in the Prose and Metrical Dindshenchas. Unpublished paper, 1996.

Colum, Padraic, ed., A Treasury of Irish Folklore. 2nd revised edition 1992, New York: Wing Books, 1954.

Ellis, Peter Berresford, The Druids. London: Constable and Company Limited, 1994.

Green, Miranda J., ed., The Celtic World. New York: Routledge, 1993.

Gregory, Lady, Irish Myths and Legends, reprint of 1910 original printing, Running Press, Philadelphia, PA, 1997.

Gwynn, Edward, The Metrical Dindshenchas, Part I. Royal Irish Academy, Todd Lecture Series, vol. VIII. Dublin: Hodges, Figgis, & Co., Ltd., 1903. The Metrical Dindshenchas, Part II. Royal Irish Academy, Todd Lecture Series, vol. IX. Dublin: Hodges, Figgis, & Co., Ltd., 1906. The Metrical Dindshenchas, Part III. Royal Irish Academy, Todd Lecture Series, vol. X. Dublin: Hodges, Figgis, & Co., Ltd., 1913. The Metrical Dindshenchas, Part IV. Royal Irish Academy, Todd Lecture Series, vol. XI. Dublin: Hodges, Figgis, & Co., Ltd., 1924. The Metrical Dindshenchas, Part V. Royal Irish Academy, Todd Lecture Series, vol. XII. Dublin: Hodges, Figgis, & Co., Ltd., 1935. (The Metrical Dindshenchas have all been reprinted 1991, Antrim: W. & G. Baird, Ltd.)

Hall, Robert L., An Archaeology of the Soul. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1997.

Hughes, Kathleen, Early Christian Ireland: Introduction to the sources. New York: Cornell University Press, 1972.

Mac Cana, Proinsias, Celtic Mythology. Revised edition. Middlesex: Newnes Books, 1983.

MacKillop, James, Dictionary of Celtic Mythology. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998.

Peacock, James, The Anthropological Lens. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1962.

Stokes, Whitley, The Prose Tales in the Rennes Dindshenchas. In Revue Celtique, vol. 15:272-336, 418-484. 1894. The Prose Tales in the Rennes Dindshenchas. In Revue Celtique, vol. 16:?1-83, 135-167, 269-312. 1895.

Zaczek, Iain, Ancient Ireland. London: Collins & Brown Limited, 1998. Chronicles of the Celts. New York: Sterling Publishing Company, Inc., 1997