Richard G. Castagna

Lawrence L. Thornton

John M. Tyrawski

GIS and Coastal Boundary Disputes: Where is Ellis Island?

When immigrants first set foot on Ellis Island, they knew they were stepping onto American soil. But where is Ellis Island? Until recently, a coastal boundary dispute between New York and New Jersey made the answer to that question uncertain. The island was originally only 3 acres, but after the federal government filled the tidal waters around the island to house and process the immigrants, the island grew to 27.5 acres. New Jersey claimed jurisdiction to all filled areas while New York insisted the entire island, no matter what its size, was hers. In 1993, the State of New Jersey petitioned the United States Supreme Court to try the dispute.

New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection (NJDEP) used GIS technology to assist the state's Attorney General in adjudicating and implementing the Supreme Court's decision in this case. To determine the actual boundary line, the NJDEP first scanned and then registered historic maps to modern ortho-photography. This paper will detail the role of GIS (Arc/Info and ArcView) in this historic decision for an historic island.

GIS Technology Reigns Supreme In Ellis Island Case

Twelve million immigrants passed through Ellis Island between 1892 and 1954. When they stepped off the boats onto the island, were they in New York or New Jersey? Last year the U.S. Supreme Court ruled on a territorial squabble between New Jersey and New York over Ellis Island that had been brewing for over 160 years.

The case involved sovereignty and jurisdiction, not ownership. The federal government owns Ellis Island. The two states asked the U.S. Supreme Court to decide whether Ellis Island was subject to New York's or New Jersey's sovereignty and jurisdiction. GIS technology played a vital role in settling this long-standing dispute.

Background

Background

Ellis Island lies in New York Bay approximately 1300 feet from the present mainland of Jersey City, New Jersey and one mile from the tip of Manhattan (Figure 1). In Colonial times, the natural island and several other islands in the shallow area west of the main shipping channel were known collectively as the Oyster Islands. Ellis Island was named for Samuel Ellis, an eighteenth century owner. It was also known as Dyer's, Bucking, and Gibbit Island during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. In this early period, the natural island was mostly mud and sand mixed with oyster shells. It was 3 acres in extent, barely rising above the water at high tide. |

The United States acquired the island in 1808 for $10,000. The Federal Government used the island as a fort until the mid-19th century. Figure 2 shows Ellis Island as Fort Gibson in 1819. The fort was built in the period immediately preceding the War of 1812. In 1991, the National Park Service unearthed twenty-five percent of the Fort Gibson wall. Two angle points in the fort wall were used as geodetic control points in a 1995 GPS investigation. These control points helped to support the alignment of the historic island with the present island. |

An 1834 compact between New York and New Jersey fixed the state boundary line at the middle of the Hudson River and the middle of New York Bay. The agreement was signed by commissioners from both states and approved by the U.S. Congress. In 1834, Ellis Island was about two and three-quarter acres in size on the New Jersey side of the boundary line between the states. This agreement allowed New York to maintain its "present jurisdiction" on all non-submerged lands of the island while New Jersey had full sovereign jurisdiction over the lands under the water surrounding the island. This complicated arrangement led to the jurisdictional boundary dispute when the island was artificially expanded with landfill.

After 1861, Ellis Island was used as a powder magazine (Figure 3, "Plan of Ellis Island, March 26, 1870"). This map shows the island as a storage facility for munitions. The first evidence of artificial filling around the natural island occurred between 1857 and 1870. The filling was relatively minor, amounting to less than one-half an acre and involving the pier area and seawall. The angle points in the Fort Gibson wall show prominently on this map.

In 1890, the United States Congress appropriated funds to expand Ellis Island into an immigration station. They began massive filling of submerged lands around the island. Ellis Island doubled in size to about 7 acres in 1890. By 1899 the island was enlarged to almost 14 acres. At first, New Jersey objected to the landfilling, but on November 30, 1904, the United States received a grant or deed from the State of New Jersey for 48 acres of submerged lands. |

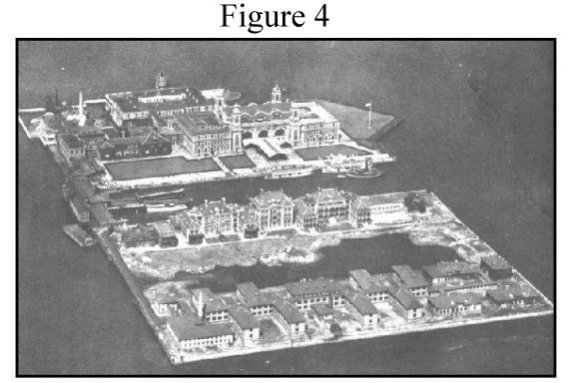

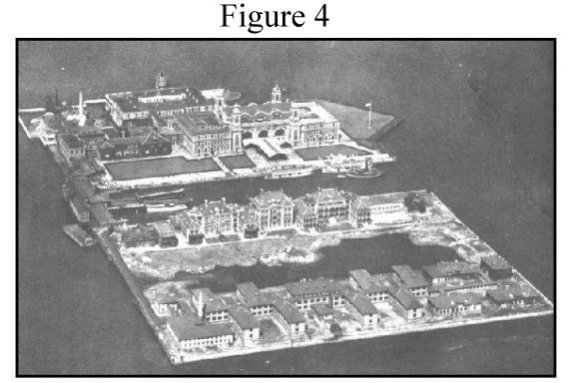

Figure 4 is an aerial photographic view of the enlarged island taken in 1921. The photo shows the dock basin between the two hospital islands partially filled in the foreground and the ongoing filling of the corner of the northwestern portion of the island in the left background . The island was expanded to over 20 acres by 1921. |

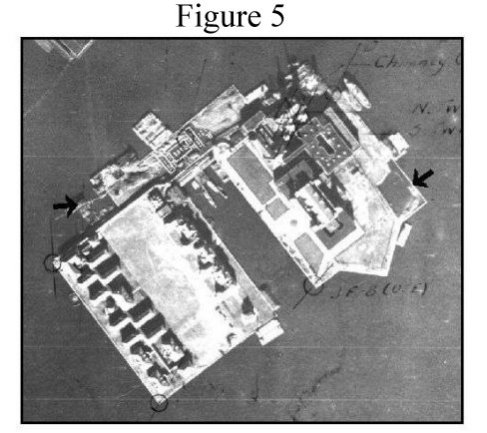

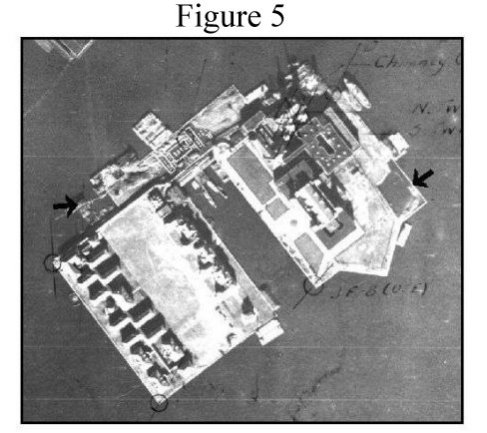

By 1934, the island had been enlarged tenfold by successive landfills from its original 2.74 acres to 27.5 acres. Figure 5 shows the last sections of Ellis Island being actively filled in November, 1934 at the eastern and northwestern ends of the island (arrows). As far back as 1890, New Jersey had contended that the filling to develop the island was done on New Jersey territory and should be subject to its sovereignty and jurisdiction. New York disagreed. |

The Role of GIS in the Lawsuit

The NJDEP mapped the natural island as part of the riparian mapping program undertaken by the Bureau of Tidelands in 1980. The mean high water line of the 1857 natural island was originally digitized by Mark Hurd Aerial Surveys of Minneapolis, Minnesota. This was done as part of a contract with the State of New Jersey to carry out the state's tidelands mapping project. The digitized line was later incorporated into the NJDEP GIS using ARC/INFO.

On April 23, 1993, using the riparian map to define the boundary line on Ellis Island, New Jersey officially asked the U.S. Supreme Court to adjudicate the boundary dispute. Utilizing GIS data, New Jersey argued that New York sovereign authority on Ellis Island was limited to the 2.74 acre natural island. The high court allowed New Jersey to pursue the action, and on October 16, 1994, appointed the Honorable Paul R. Verkuil, Jr., Esq. as Special Master. The case concerned original jurisdiction, a constitutional provision that gives the high court exclusive jurisdiction over lawsuits between states.

The historic six-week trial was held during the summer of 1996 in the U.S. Supreme Court building on Capitol Hill and, in part, on Ellis Island. The Special Master reviewed all testimony and historical records provided by the states to support their arguments. He then submitted a report to the full Supreme Court summarizing the evidence and making a recommendation on the settlement.

To prepare for the trial, Richard Castagna of the NJDEP Bureau of Tidelands, assisted by John Tyrawski and Lawrence Thornton of the NJDEP GIS Unit, and Robert Cubberley of the NJDEP Land Use Regulation Program, prepared several maps on the GIS showing the proposed boundary line. The line was based on the 1857 U.S. Coast Survey (Figure 6). |

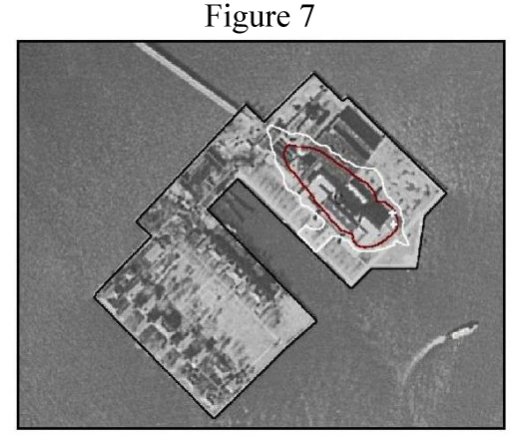

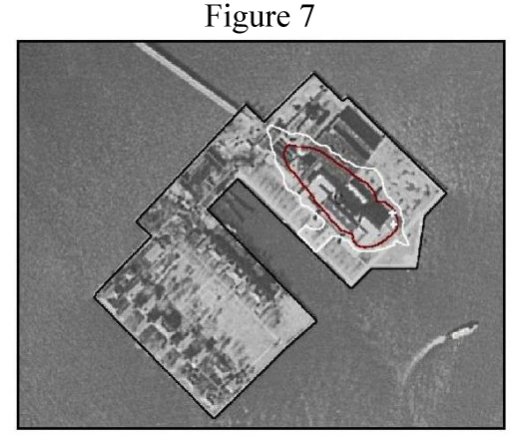

Surveyors from the Geodetic Section of the New Jersey Department of Transportation (NJDOT) used GPS surveying technology to survey the perimeter of the existing island as well the locations of two angle points in the Fort Gibson wall (Figure 7). The location of the original wall (which was excavated in part) was essential in supporting the alignment of the 1857 historical survey used to define New Jersey's jurisdictional claim. Trial testimony explained the GPS techniques used to survey Ellis Island.

In addition, the use of GIS in determining the size of the natural island to the mean high water line was explained to the court. New York's attorney objected to the use of GIS to determine the size of Ellis Island because the GIS equipment had not physically been brought into the Supreme Court building. She argued, "This is a New Jersey system that we never had access to; we were never invited to look at it. I object." Special Master Paul Verkeil overruled New York's objection. He said, "The system itself is not introduced into evidence, but it needn't be. It's just what you were relying on earlier." His point was that the GIS generated data had already been explained in pre-trial documents, so it was unnecessary to bring the GIS system into the court room. All parties had had access to the GIS data. |

When the Special Master reviewed all of the evidence he determined that the 1857 U.S. Coast Survey map was the most reliable map and should define the boundary between the two states. In his final report he stated, "I find that the 1857 United States survey map advocated by New Jersey for use in delineating the boundaries on Ellis Island most accurately depicts the size and shape of the original Ellis Island." In addition, he was convinced that New Jersey had accurately positioned the natural 1857 U.S. Coast Survey Map on a 1995 survey of the island. He was convinced that the alignment of the natural 1857 island with the present island was highly accurate because of the GPS survey of Fort Gibson wall angle points.

The Special Master, however, disagreed with New Jersey's use of the mean high water line on the island as the boundary, arguing that the low water line would be a more accurate boundary. In May of 1998, after oral arguments were presented by the states, the U.S. Supreme Court determined that the low water line of the natural island be used to delineate the jurisdictional boundary. The Special Master's directed the State's to use the 1857 survey based on the high court's 6-3 decision.

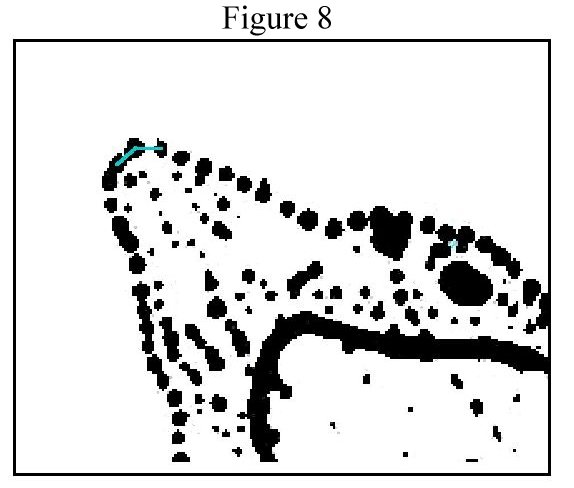

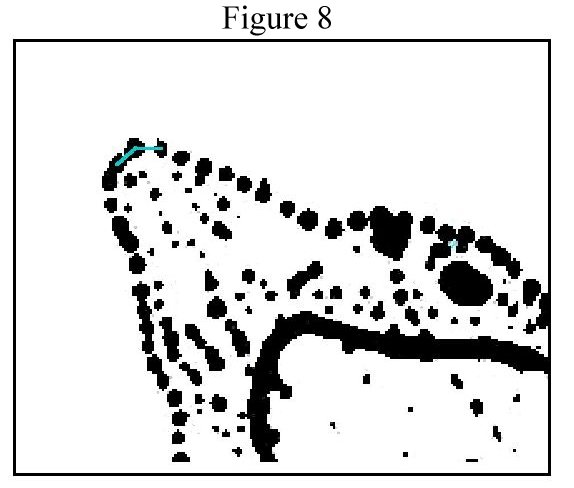

The NJDEP was directed to prepare the Ellis Island boundary based on the Supreme Court's decision. The mapping was completed using the GIS. The 1857 U.S. Coast Survey Map was scanned and captured as a tiff image file. The image file was then brought into Arcview, and the low water line captured as an edit function. The line depicting low water was represented on the 1857 survey by a series of dots (Figure 8). The center of each dot was used to enter each point to define the low water boundary. Once completed, the points and the line they describe were given geographic referencing by first converting the shape files to coverages, creating tic files for each, and then transforming and projecting the coverages to New Jersey State Plane Feet, NAD83. With this referencing, the line could be plotted on the department's 1995 digital imagery, as well as be integrated into the outer boundary survey that was completed with the GPS surveying done by Lou Marchuk of NJDOT. The line was then ungenerated and sent to NJDOT to prepare a metes and bounds description of the boundary and a final hardcopy map. |

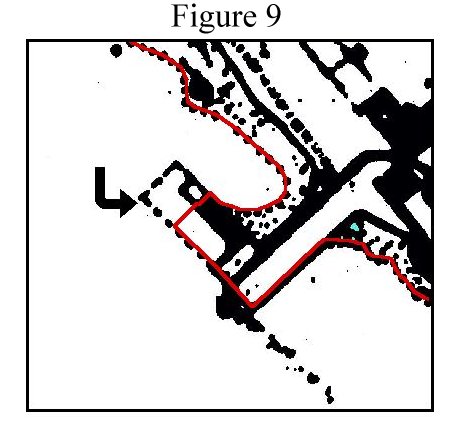

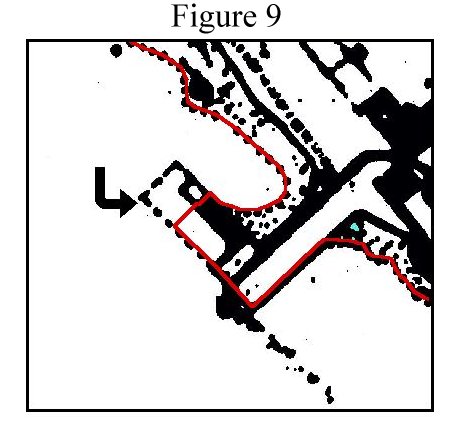

The map was then presented to the state of New York, who subsequently approved of the boundary delineation after several minor changes. One of these changes involved the interpretation of a dashed line in the vicinity of the 1857 pier (Figure 9). There was disagreement as to whether the L shaped area within the dashed lines was above or below the low water mark (arrow). The conflict was resolved by an agreement to grant each state one half of the disputed area. Using GIS techniques, the 4,178 square foot area involved in the contested site was divided in half, each state receiving 2,089 square feet. |

After over 160 years, the jurisdictional fight over Ellis Island is finally over. The United States Supreme Court accepted the final map and New York was granted jurisdiction to 4.68 acres. This area includes almost all of the main immigration building as well as portions of the Wall of Honor, baggage handling/dormitory building, power house and administration building (Figure 10). The New York portion of Ellis Island is landlocked, enclaved within New Jersey's territory. New Jersey has sovereign authority over the remaining 22.80 acres of the island that includes portions of the above buildings, the ferry house, and all of the 29 hospital and dormitory buildings located on the southern portion of the island. The size of each state's territory was determined with GIS. |

Conclusion

The Ellis Island case probably represents the first use of GIS to present and implement a boundary dispute before the U.S. Supreme Court. The success and power of GIS in this case indicates that it probably will not be the last. Finally, for all those who either came through Ellis Island or who had ancestors that did, now know the facts. They came to America and set foot in both New York and New Jersey.

Acknowledgments:

Special Thanks to the Following Individuals:

Lou Marchuk, NJDOT

Robert Cubberley, NJDEP

MaryAnn Scott, NJGS

Bill Andersen, DAG

Andrew Weirback, NJDEP

Edith Page Thornton, U. of Wis. |

Final Survey Description of the Island

Preliminary Field Work

Scan of 1857 Coast Survey

Document and Case Preparation

AutoCad Maps

Editing |

Endnotes:

The U. S. Supreme Court issued its final decree and approved the boundary line as mapped by the NJDEP on May 17, 1999. The high court stated:

"It is Hereby Ordered, Adjudged, and Decreed as Follows:

The State of New Jersey's prayer that she be declared to be sovereign over the landfilled portions of Ellis Island added by the Federal Government after 1834 is granted and the State of New York is enjoined from enforcing her laws or asserting sovereignty over the portions of Ellis Island that lie within the State of New Jersey's sovereign boundary as set forth in paragraph 4 of this decree."

Paragraph 4 is the ungenerated coordinates in courses and distances of the line mapped by the NJDEP.

References:

Castagna, RG (1995) Expert Report of Richard G. Castagna. Report prepared for the State of New Jersey, State of New Jersey v. State of New York, Supreme Court of the United States (Original 120), 100pp.

Castagna, RG (1996) Testimony, United States Supreme Court, West Conference Room, Washington, D.C. State of New Jersey v. State of New York, Supreme Court of the United States, No 120 Original, p316, 317.

DeAlmedida, P., Horowtz, R. (1996) Brief of New Jersey in Support of its Motion for Summary Judgement, for State of New Jersey v. State of New York, Supreme Court of the United States (Original 120), 115pp.

Pitkin, (1975) Thomas M. Keepers of the Gate: A History of Ellis Island (New York University Press)

Supreme Court of the United States (1998) State of New Jersey, Plaintiff v. State of New York, No. 120. Original, Final Decision, 30pp.

Supreme Court of the United States (1999) Final Decree, 13pp.

Verkuil, P.R. (1997) State of New Jersey v State of New York, Final Report of the Special Master, Supreme Court of the United States, No 120 Original, 170pp and appendices

Author Information:

Richard G. Castagna, Regional Supervisor, New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection, Bureau of Tidelands, 9 Ewing Street, Trenton, New Jersey 08625. (609) 633-7956 (609) 633-6493 (FAX) rcastagn@dep.state.nj.us

Lawrence L. Thornton, Research Scientist, Bureau of Geographic Information and Analysis, New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection, P.O. Box 428, Trenton, New Jersey 08625. (609) 984-2243. (609) 292-7900 (FAX)

larryt@gis.dep.state.nj.us

John M. Tyrawski, Research Scientist, Bureau of Geographic Information and Analysis, New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection, P.O. Box 428, Trenton, New Jersey 08625. (609) 984-2243. (609) 292-7900 (FAX) johnt@gis.dep.state.nj.us

Background

Background