History with GIS: Mapping Through Georgia

Steve Mashburn

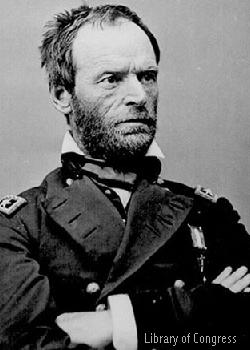

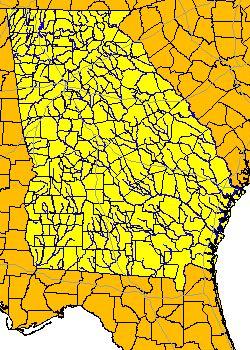

The "Mapping Through Georgia" project uses ArcView to display the political, economic, and social themes contained in the 1860 Federal Census of Georgia. Discussion will focus on how to get historical census information into a database and how to create shape files that display proper historical county boundaries. This project was inspired by the fact that Sherman used the 1860 census to guide his "march to the sea" during the later part of the American Civil War.

The Census - Two Internet Viewpoints

On 12 March 2002, in order to celebrate the birthday of the United States Census Bureau, Representative LaTourette of Ohio in House Resolution #339 proclaimed that "throughout our history, censuses have been used to mark significant achievements and milestones in our Nation's history. . . In 1864, General Sherman would use published information on population and agriculture in his war-planning efforts" (Census Bureau). He then cites several other examples of significant achievements through the use of the census.

On 12 March 2002, in order to celebrate the birthday of the United States Census Bureau, Representative LaTourette of Ohio in House Resolution #339 proclaimed that "throughout our history, censuses have been used to mark significant achievements and milestones in our Nation's history. . . In 1864, General Sherman would use published information on population and agriculture in his war-planning efforts" (Census Bureau). He then cites several other examples of significant achievements through the use of the census.

A differing opinion is expressed, however, by Carl Watner in an online article entitled "Count Me Out!" for the Daily Freedom web site. Along with several examples of the government's misuse of the census, Watner makes the following statement: "on his march through Georgia, near the end of the Civil War, Gen. William T. Sherman used a map annotated with county-by-county livestock and crop information to help his troops live off the land." Watner then exhorts us to fight against the infringement of the government into our personal lives (Freedom Daily).

So it appears that even after one hundred thirty-seven years, one's opinion of General Sherman's March to the Sea is highly colored by one's politics. The question of the legality of Sherman's actions or even his greatness as a military hero is a question open for debate, but most sources appear to agree on at least one fact: Sherman was the 19th century's answer to data mining.

Even General Grant commented that Sherman "bones all the time while he is awake, as much on horseback as in camp or in his quarters" and this opinion has been adopted by many Civil War historians and writers, including Burke Davis who states: "Sherman had chosen his route after pouring over census reports of farm production county-by-county so that he could lead his troops through the regions richest in provisions" (Davis 27).

However, did Sherman in the actuality use the Eighth Federal Census? "I had obtained not only the United States census-tables of 1860," Sherman wrote in his Memoirs, "but a compilation made by the Controller of the State of Georgia for the purpose of taxation, containing in considerable detail the 'population and statistics' of every county in Georgia" (Sherman).

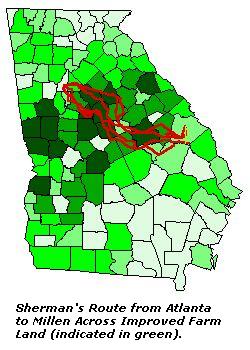

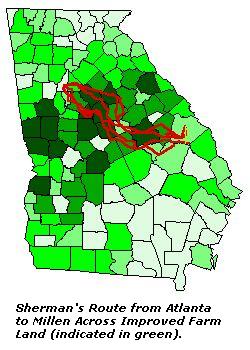

Now the question for us is, can the emphasis given to the census data's role in Sherman's march be justified? Using ArcView, we will spatially display data from the 1860 census data and then determine if such data foreshadows the infamous route that Sherman took just four years later.

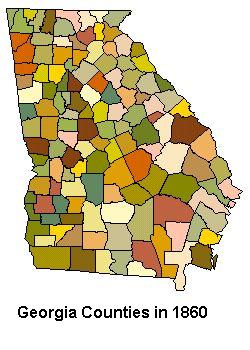

In order to understand the county line of 1860, let's briefly look at the historical development of the political geography in Georgia.

Headright System

The first land in Georgia was distributed on the headright system---200 acres on a man's "head" and 50 acres for his wife, 50 acres for each child, and 50 acres for each slave up to 1000 acres. As a result the earliest counties (those in the southeast portion of the state) were laid out according to rivers and other natural boundaries as well as these irregularly formed headright grants. (Georgia Counties 4).

Land Lottery

In 1807 Georgia gained new land from a treaty with the Indians. This land was divided into counties and the counties were divided into land districts as square as possible. Then the land districts were subdivided into square, farm-sized land lots. The government, anxious to create settlements as fast as possible, distributed land by a lottery. Additional lotteries were held in 1820, 1821, 1827 and 1832 (Georgia Counties 3-5).

County seats were chosen in a central location within each county, and by drawing circle around the courthouse at a certain distance the city limits were set. This pattern of settlement made Georgia "a land of square farms and round towns" (Kennett 19).

County Formations by Division and SubDivision

The formation of new Georgia counties did not stop with the last Land Lottery of 1832. "Counties were created from other counties and more counties were created from those counties.

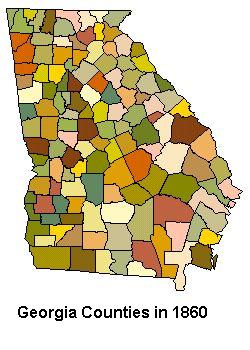

Mapping the Georgia Counties of 1860

The constant creation of new counties out of existing ones naturally entails many problems for us in generating a 1860 map of Georgia for use in ArcView. While a line map showing the county outlines might be useful, in order to do statistic work with the census data, we need to obtain a polygon shape file.

The constant creation of new counties out of existing ones naturally entails many problems for us in generating a 1860 map of Georgia for use in ArcView. While a line map showing the county outlines might be useful, in order to do statistic work with the census data, we need to obtain a polygon shape file.

There are three solutions:

1. Use Horan and Hargis's County Longitudinal Template.

2. Digitize and geo-reference an historical map.

3. Modify a current county shape file.

Horan and Hargis's County Longitudinal Template

The County Longitudinal Template designed by Horan and Hargis allows researchers to transform the geographic boundaries of counties in the United States back to their original form.

"These data provide a decade-by-decade account of the administrative status of each county, starting in 1990 and tracing each census period back through 1840. The first four variables are the county name, ICPSR state code, FIPS code, and ICPSR county code. These four variables allow the researcher to select the counties for the state in question. The next 16 variables are ID variables for each census year, 1990 back to 1840. The last 13 variables are boundary change flags for each census year from 1960 to 1840" (Horan).

This method was set aside as being too unyielding for use with school-age children. The inaccessibility of the template and data files to non-members of the Inter-University Consortium for political and Social Research was also a factor in our decision not to use it.

Digitize and Geo-reference a Historical Map

The method of digitizing and geo-referencing a historical map was tried and was found to be workable. There are several historical maps of Georgia counties during this time period available on the Internet. However, since there are copyright issues with using online materials, this might not be the best solution for those who are interested in doing a similar project with their classes.

The method of digitizing and geo-referencing a historical map was tried and was found to be workable. There are several historical maps of Georgia counties during this time period available on the Internet. However, since there are copyright issues with using online materials, this might not be the best solution for those who are interested in doing a similar project with their classes.

Modify a Current County Shape File

Modifying a shape file of the modern Georgia counties proved to be easier than we at first thought it would be. The heads-up digitizing tools that come in ArcView were all we needed to transform the modern counties into the 1860 counties. By looking at several historical maps, one could easily eyeball the 1860 county lines. Of course, this system is only as accurate as the user, but for our purposes it worked very well.

We found displaying a Georgia river theme while we were drawing our counties was useful for many of the old lines followed a river. Another trick we discovered was that by displaying towns, mountains, lakes and other physical features we got reference points that allowed us to get a fairly accurate rendering of the old county lines.

The 1860 Federal Census of Georgia

Now that we have the map, we will need census data. Historical census data is available at most large libraries on microfilm. A class of twenty to thirty students can abstract a great deal of data in one class period. When abstracting data it is wise to set up a system of verifying the students' data entry. Digitized census data is becoming more available both in compiled text versions and in scans of the original documents.

We found that entering the census data in Excel and then converting to a comma delimited text file worked well. We used the county name as our common field since the FTP numbers are only good for modern counties.

The 1860 Census is interesting because of the way that the demographic and economic statistics come together in light of the upcoming conflict. 44% of the state's population (blacks) represented 45% of its wealth, and that value was twice as much as the value of the land.

"The vast majority of slave owners owned less than twenty slaves and were no strangers to hard work themselves, however, the majority of Georgians owned no slaves" (Kennett 18-20). Cotton was King but it was an uneasy rule. In 1860 cotton barely surpassed corn in market value.

During the war restrictions on cotton production stimulated production of farm products so that Georgia became a vast harvest of corn, wheat, sugar, lumber, rice and livestock. Many Union soldiers wrote home about seeing produce and livestock in abundance. Sherman himself refers to Georgia as "literally a land overflowing with milk and honey" (Mills xiv). "Georgia has a million inhabitants," he said. "If they can live, we should not starve." (Davis 27).

Sherman's Background in Georgia

In the 1840's, after his graduation from West Point, Sherman spent considerable time in north Georgia on army assignments. While taking depositions for Seminole War pensions he visited Marietta, Kennesaw Mountain, and Allatoona, all sites he would later visit again. He became friendly with a Colonel Tumlin of Cartersville and kept a correspondence with him for a number of years.

In the 1840's, after his graduation from West Point, Sherman spent considerable time in north Georgia on army assignments. While taking depositions for Seminole War pensions he visited Marietta, Kennesaw Mountain, and Allatoona, all sites he would later visit again. He became friendly with a Colonel Tumlin of Cartersville and kept a correspondence with him for a number of years.

Therefore, on the eve of his invasion of Georgia, he had not only a considerable mass of data on the state's economy and resources, but he was also personally knowledgeable about the state's topology and social structures.

As his troops moved into Georgia from Chattanooga they begin to find the land lot maps in the courthouses. These proved to be a boom for his Topographical Engineers. Lot numbers become handy reference points for the map makers to embellish, fill out and supplement. In one message to General MacPherson, Sherman said that he could be found in a house "not far from the northwest corner of lot 273" (McElfresh ). It was as if Georgia itself had created a perfect set of grid lines to guide Sherman's army through the hills of north Georgia.

Setting the Goal

After taking Atlanta, Sherman chased Hood northward to Rome but turned back to Atlanta when it became apparent that Hood was trying to lead Sherman away from Georgia. On September 4th Sherman suggested that Federal forces from the Gulf surround Mobile then march to Montgomery and Selma. He would move through LaGrange and West Point and combine with the Gulf force to crush the city of Columbus. The benefit of that plan would be to open the Chattahoochee and Apalachicola rivers to Federal traffic.

On September 10th Sherman expressed the thought that he could capture Milledgeville then turn on Macon or Augusta and then "sweep the whole State of Georgia." Ten days later he told Grant, "I would not hesitate to cross the State of Georgia with sixty thousand men hauling some stores and depending upon the country for the balance" (Miles 9).

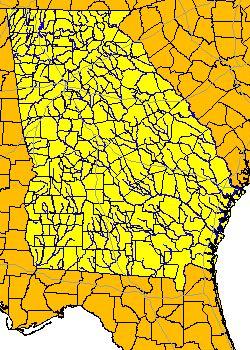

The decision to march to the sea was largely due to the fact that "…the heartland of the Confederacy still produced large amounts of food and munitions to supply its armies, and the will of the southern people to prosecute the war seemed undeterred...(Miles 5).

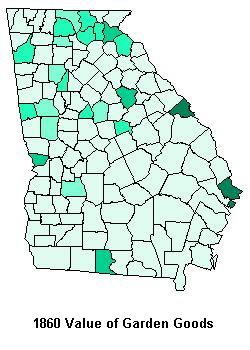

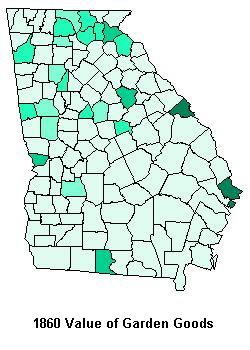

Although by looking at the value of garden goods in 1860, one might assume that Sherman was not following the census. However, when one realizes that Sherman knew that the whole of Georgia was producing garden goods now that they were at war, one would be wise to look at where the most improved farm land was located---that's is where the Confederate bread basket would be found.

Strategic Necessity

To destroy as much of the railroad that ran along the Ogeechee River as possible became the strategic necessity of Sherman's March to the Sea. This railroad was a major artery between central Georgia and the rail systems that ran from Augusta and Savannah northward. General Robert E. Lee, who was under siege at Petersburg, Virginia, was dependent upon these railroads for supplies and munitions. The junction at Millen was especially critical.

Tactical Necessity

Sherman's men were veterans, most in their second enlistment. He knew he had little to fear from the small militia units that were the only Confederate forces left in the state. Hood's army, in northern Alabama, was too far away to catch him in the rear and Lee had no men to spare to send down to oppose him.

Under these circumstances, Sherman chose to ignore conventional wisdom and to divide his 60,000 men into two columns along each side of the Ogeechee River. Major-General Henry D. Slocum commanded the left wing, composed of two corps. Major-General Oliver O. Howard commanded the right wing, also composed of two corps.

Placing two corps on both sides of the river insured that each corps had sufficient areas in which to forage for food and animals. In addition, this operation allowed that any attacking enemy force to be flanked by the other Federal force on the other side of the river.

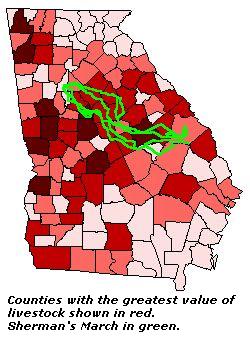

Draft Animals

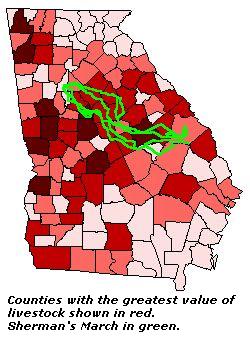

When we come to the issue of livestock, it becomes apparent that Sherman did indeed use the census data. The horses and mules that had left Atlanta on the march through Georgia were the best available in the city, but they were the best of a sorry lot and incapable of making a long march. The artillery would need an entire new supply of horses.

When we come to the issue of livestock, it becomes apparent that Sherman did indeed use the census data. The horses and mules that had left Atlanta on the march through Georgia were the best available in the city, but they were the best of a sorry lot and incapable of making a long march. The artillery would need an entire new supply of horses.

"As to our mules and horses, we left Atlanta with about 2,500 wagons, many of which were drawn by mules which had not recovered from the Chattanooga starvation. . . " (Official Records 726).

Why would Sherman leave Atlanta with his stock in such bad condition? Many men worried about it and were pleasantly surprised. One soldier remarked, "Had we not been able to capture a large number of mules and horses during the first week it would have been impossible to have brought the train with us" (Kennett 252).

Even Sherman is pleased: ". . . [all of the broken-down horses] were replaced, the poor mules shot, and our transportation is now in superb condition" (Official Records 726). Without a doubt, he knew through the census that he would find enough livestock in the central Georgia counties on the way to Savannah.

In fact, seizures of horse and mules far exceeded the amount needed. Those that were brought in were sorted and the best replaced weaker, broken-down animals in the wagon trains. The culling of horseflesh went on constantly so that at the end of the march, the army had better animals that it did when it left Atlanta.

"I have no doubt the State of Georgia has lost by our operation, 15,000 first-rate mules." Sherman exclaims in a message to Grant "As to horses, Kilpatrick collected all his remounts, and it looks to me, in riding along our columns, as though every officer had three or four led horses, and each regiment seems to be followed by at least fifty Negroes and foot-sore soldiers riding on horses and mules. The custom was for each brigade to send out daily a foraging-party of about fifty men, on foot, who invariably returned mounted, with several wagons loaded with poultry, potatoes, &c.; and as the army is composed of about forty brigades you can estimate approximately the number of horses collected (Official Records 726).

Where's the Beef?

"We started with about 5,000 head of cattle, and arrived with over 10,000; of course, consuming mostly turkeys, chickens, sheep, hogs, and the cattle of the country (Official Records 726).

For Sherman to arrive in Savannah with one beef cow for every six men is an indication of just how rich the area he passed through had been.

Sherman's Impact

As great the impact was on the march ending the Civil War, "there is no compelling evidence that Sherman's army left a residual effect on land use on the Upper Coastal Plain of Georgia" (Pinder). Social and political ideals sometimes last longer than environmental changes and for one hundred years the region suffered economically as a result of the Civil War. The current map of the state, however, shows Georgia marching towards a bright future.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Dr. John E. Pinder for the very useful overview he provided to me over the military aspects of Sherman's March to the Sea.

Reference

Bryant, Pat. Georgia Counties: Their Changing Boundaries. Atlanta: State Printing Office, 1977.

Davis, Burke. Sherman's March. New York: Random House, 1980.

Davis, George B., Leslie J. Perry and Joseph W. Kirkley. Official Military Atlas of the Civil War. New York: Arno Press, c1978.

Drummond, William J. Historical Geographic Information Systems: Mapping the Economic Effects of the Civil War. (website) http://civilwar.gatech.edu/histgis/

Freedom Daily. (website) www.fff.org/freedom/0600e.asp

Horan, Patrick M., and Peggy G. Hargis. County Longitudinal Template 1840-1990 [Computer file]. ICPSR version. Athens, GA: Patrick M. Horan, University of Georgia, Dept. of Sociology/Statesboro, GA: Peggy G. Hargis, Georgia Southern University, Dept. of Sociology and

Anthropology [producers], 1995. Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor], 1995.

Kennett, Lee. Marching Through Georgia: The Story of Soldiers and Civilians During Sherman's Campaign. New York, NY: HarperCollins,

1995.

Marching through Georgia: William T. Sherman's Personal Narrative of His March Through Georgia. Mills Lane, ed. New York: Arno Press, 1978, 1974.

McElfresh, Earl B. Maps and Mapmakers of the Civil War. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Publishers, 1999.

Miles, Jim. To the Sea: A History and Tour Guide of Sherman's March. Nashville: Ritledge Press, 1989.

Pinder, J. E. Personal Email to Steve Mashburn, June 17, 2001

Pinder, J. E., E. M. Jahnke and T. E. Rea. Sherman's March to the Sea: Using Remote Sensing to Test for Residual Effects on the Georgia Landscape. Manuscript.

Scaife, William R. The March to the Sea. Atlanta: W.R. Scaife, 1989.

Smith, J. Harmon. (Map) The State of Georgia, showing the major

campaign areas and engagement sites of the War between the States,

1861-1865. Atlanta: Georgia Dept. of Commerce, 1961.

Thorndale, William and William Dollarhide. U.S. Federal Censuses, 1790-1920. Baltimore: Genealogical Pub. Co., 1995.

U.S. Census Bureau Website. http://www.census.gov/mso/www/centennial/hcr339.htm

U.S. War Department. The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the

Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies (Washington:

U.S. Government Printing Office, 1893, reprinted by The National

Historical Society, 1971), Series I, Vol. XLIV, pp. 726-728.

Steve Mashburn

Instructional Technology Specialist

North Forsyth High School

Coal Mountain Drive

Cumming, GA 30040

smashburn@forsyth.k12.ga.us

On 12 March 2002, in order to celebrate the birthday of the United States Census Bureau, Representative LaTourette of Ohio in House Resolution #339 proclaimed that "throughout our history, censuses have been used to mark significant achievements and milestones in our Nation's history. . . In 1864, General Sherman would use published information on population and agriculture in his war-planning efforts" (Census Bureau). He then cites several other examples of significant achievements through the use of the census.

On 12 March 2002, in order to celebrate the birthday of the United States Census Bureau, Representative LaTourette of Ohio in House Resolution #339 proclaimed that "throughout our history, censuses have been used to mark significant achievements and milestones in our Nation's history. . . In 1864, General Sherman would use published information on population and agriculture in his war-planning efforts" (Census Bureau). He then cites several other examples of significant achievements through the use of the census.

The constant creation of new counties out of existing ones naturally entails many problems for us in generating a 1860 map of Georgia for use in ArcView. While a line map showing the county outlines might be useful, in order to do statistic work with the census data, we need to obtain a polygon shape file.

The constant creation of new counties out of existing ones naturally entails many problems for us in generating a 1860 map of Georgia for use in ArcView. While a line map showing the county outlines might be useful, in order to do statistic work with the census data, we need to obtain a polygon shape file.

The method of digitizing and geo-referencing a historical map was tried and was found to be workable. There are several historical maps of Georgia counties during this time period available on the Internet. However, since there are copyright issues with using online materials, this might not be the best solution for those who are interested in doing a similar project with their classes.

The method of digitizing and geo-referencing a historical map was tried and was found to be workable. There are several historical maps of Georgia counties during this time period available on the Internet. However, since there are copyright issues with using online materials, this might not be the best solution for those who are interested in doing a similar project with their classes.

In the 1840's, after his graduation from West Point, Sherman spent considerable time in north Georgia on army assignments. While taking depositions for Seminole War pensions he visited Marietta, Kennesaw Mountain, and Allatoona, all sites he would later visit again. He became friendly with a Colonel Tumlin of Cartersville and kept a correspondence with him for a number of years.

In the 1840's, after his graduation from West Point, Sherman spent considerable time in north Georgia on army assignments. While taking depositions for Seminole War pensions he visited Marietta, Kennesaw Mountain, and Allatoona, all sites he would later visit again. He became friendly with a Colonel Tumlin of Cartersville and kept a correspondence with him for a number of years.

When we come to the issue of livestock, it becomes apparent that Sherman did indeed use the census data. The horses and mules that had left Atlanta on the march through Georgia were the best available in the city, but they were the best of a sorry lot and incapable of making a long march. The artillery would need an entire new supply of horses.

When we come to the issue of livestock, it becomes apparent that Sherman did indeed use the census data. The horses and mules that had left Atlanta on the march through Georgia were the best available in the city, but they were the best of a sorry lot and incapable of making a long march. The artillery would need an entire new supply of horses.