Globally, tigers (Panthera tigris spp.) are in crisis and populations of all five subspecies of tiger appear to be in decline, with the possible exception of the Amur tiger (P. t. altaica) in the Russian Far East (Seidensticker et al. 1999). Concern for the long-term future of the world's largest cat has resulted in unprecedented efforts around the world to establish programs to better understand the reasons for this decline and to develop conservation and management programs to secure a future for these animals (Tilson et al. 2000).

Nowhere has the tiger crisis been more evident than in the Republic of Indonesia, once home to three of the world’s eight known subspecies of tiger. Sometime near the middle of the twentieth century, the Bali tiger (P. t. balica) disappeared from its 5,560 km2 island home (Seidensticker 1987). A quarter of a century ago the last Javan tiger (P. t. sondaica) disappeared forever from its last holdout, Meru Betiri National Park in eastern Java (Hoogerwerf 1970, Seidensticker 1987). Today, Indonesia's last 500 wild tigers, the Sumatran (P. t. sumatrae), inhabits only a fraction of its former range on the island of Sumatra and its future is far from secure (Franklin et al. 1999, Tilson et al. 1994) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Picture of wild Sumatran tiger captured using an infra-red camera unit, Way Kambas National Park, Sumatra, Indonesia. (Photo courtesy of: Directorate General of Nature Protection and Conservation, Ministry of Forestry and Estate Crops, Republic of Indonesia, Sumatran Tiger Project)

Several factors have resulted in this decline of tigers and other large mammals in Sumatra. Habitat loss may be the most significant factor. Since 1900, an estimated 80% of tropical forest habitat that once covered the island has now been converted (Collins et al. 1991, Whitten et al. 1987). What habitat remains is increasingly fragmented, isolated, and degraded. An estimated 75% of the remaining wild Sumatran tigers are thought to inhabit the island's six national parks, all of which have been logged to some extent, and the tigers outside these protected areas are thought to occur only in very small, isolated, habitat islands (Tilson et al. 1994). This degradation of habitat includes the hunting of tiger prey species, the abundance of which are a significant factor affecting the density of tigers in any given area. Finally, illegal hunting of tigers themselves and killing of "problem tigers" as a result of conflict with humans and their livestock has had an impact on these populations (Tilson and Nyhus 1998).

Ultimately, the reasons for the decline of the tiger and its habitat in Indonesia are related to rapid human population growth; development of the forestry, agriculture, and plantation sectors; and the direct and indirect impacts of natural disasters, such as fires, and political and economic volatility (Nyhus et al. 1999, Nyhus 1999).

Despite international recognition of the problem facing tigers in Indonesia, we still know relatively little about the abundance, distribution, or threats facing the country’s last populations of wild tigers or much about its remaining habitat (CITES 1999, Tilson et al. 1994). One of the reasons for this limited information is that the island is large (roughly the size of California), the terrain is rugged--with volcanic mountain peeks reaching 3,800m in the western Bukit Barisan mountain range and vast swamp forest along its east coast--and access to many areas remains difficult because of limited infrastructure and heavy rains during much of the year. Another reason is related to the tiger itself. While it is the island’s largest carnivore, it is also one of its most elusive animals and is infrequently observed in the wild.

To address these challenges, an international and interdisciplinary effort has been underway since 1994 to better understand the reasons for the decline of Sumatran tiger populations and to use this information to develop sustainable conservation and management strategies to secure its future in the wild (Nyhus et al. In press, Tilson et al. in press, Tilson et al. 1997). Under the umbrella of the Sumatran Tiger Project, Indonesian and international researchers are working with the Indonesian government to study the conservation biology of the Sumatran tiger, including its distribution, abundance, habitat requirements, and behavior; the human dimension of tiger conservation, including how people living near tiger habitat perceive and interact with these animals; and developing methods to link in-situ (field) and ex-situ (captive) conservation programs.

Geographic information systems are being used to study the ecology and conservation status of tigers around the world (Dinerstein et al. 1997, Smith et al. 1999). In this paper we address how GIS and remote sensing are being used in combination with other high- and low-technology methods in the field in Sumatra, Indonesia, to better understand the reasons for the decline of these animals and to develop long term monitoring and conservation efforts to secure a future for the last wild tigers in Indonesia. We illustrate how GIS can be used effectively by field researchers and support staff where conditions are rugged and technical tools and literacy limited. We suggest this strategy is an effective approach to link field and GIS researchers, and offers a model for others carrying out similar studies.

One of the activities central to tiger research and conservation efforts in Sumatra is the mapping of the tigers’ habitat and threats using GIS. Since the project’s inception, the following GIS activities have been carried out in support of its mission.

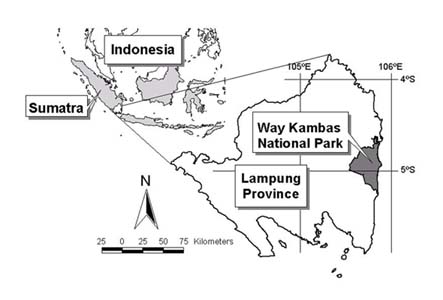

The project’s first GIS efforts were launched in Way Kambas National Park in southern Sumatra (Figure 2). One of the smallest national parks in Sumatra, Way Kambas was chosen as the project’s first study site because it is the one of the last remaining lowland rainforests in Sumatra and an area of conservation concern (Franklin et al. 1999). Its proximity to major urban areas, the relative paucity of information about tiger and other wildlife within the park, and high human population densities surrounding the protected area were also reasons it was chosen.

Figure 2. Location of Way Kambas National Park, Lampung, Sumatra, Indonesia.

Maps from the Indonesian government’s national mapping agency (Pembentukan Badan Koordinasi Survey dan Pemetaan Nasional, BAKOSURTANAL) were digitized to develop a base map of the park and its surrounding areas (Franklin et al. 1999). A Landsate Thematic Mapper (TM) image was registered using global positioning system (GPS) ground control points and classified (Figure 3). These land cover classes are being edited and refined to eventually update habitat maps of the park, to assist in the analysis of tiger biology research, and for future conservation planning and management.

Figure 3. Sample of classified Landsat TM image of Way Kambas National Park, Sumatra, Indonesia. The image shows the sharp distinction between the park's vegetation zones (dark green) and neighboring agricultural fields (purple).

A series of infra-red remote camera units were set up in the park to monitor the abundance and behavior of tigers and other mammals. By the end of 1999, more than 13,000 photographs were obtained from these cameras, including more than 300 photographs of tigers. At least 37 individual tigers have been identified (STP 1999). This database is linked to the GIS and has already been used to study home range for resident tigers (Franklin et al. 1999).

A second effort was to expand this GIS map of tiger habitat to the entire province of Lampung, one of eight provinces on the island. Digital GIS data were obtained from the Indonesian government’s mapping department (Bakkosurtanal) and the Indonesian government’s National Forest Inventory (NFI) project through the Ministry of Forestry.

These maps, used in conjunction with existing Indonesian government paper maps, suggested that close to one-third of the province’s 33,307 km2 area was potential tiger habitat (Figure 4). Most of this area included two national parks and a number of "Protection Forests," forests intended for soil and water conservation and wildlife but with relatively little protection from forest rangers.

Figure 4. Potential tiger habitat in Lampung Province, Sumatra, indicated as shades of green based on official habitat designations

Ground truthing by teams of researchers in the field found these initial estimates to be unfortunately overly optimistic. Of the more than 50 potential tiger habitat fragments identified (9,367 km2), only six were found to show signs of tigers, and only two (the national parks) had tigers in any abundance (Tilson et al. in preparation). The preliminary results of these field checks suggest that less than 6,000 km2 (18%) of the Province is likely to contain viable tiger habitat, and only approximately 1,000 km2 of this habitat occurs outside of the Province’s two national parks (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Actual tiger distribution based on field surveys (locations where tigers found represented as red dots).

Third, these methods are now being expanded to cover the entire island of Sumatra, an area roughly the size of California. The goal is to identify habitat fragments that do or can contain tigers to develop a priority list for Indonesian conservation managers to consider. By 2001, we hope to complete an assessment of most of the southern half of the island. The data sets that are being used in this assessment include the NFI and BAKOSURTANAL GIS data mentioned above, several Landsat TM images covering suspected tiger habitat, and information from field teams. Preliminary analyses have already identified a possible habitat corridor linking Berbak and Bukit Tigapuluh national parks in central Sumatra (Figure 6) and we are confident that these assessments will provide a list of priority tiger conservation areas that can be used by Indonesian conservation authorities.

Figure 6. Potential tiger habitat corridor linking Berbak and Bukit Tigapuluh National Parks, Sumatra (Sullivan 2000).

These Sumatra-wide assessments will also be compared to GIS maps developed by an international consortium of conservation organizations to identify priority tiger habitat across Asia using a set of ecosystem indicators (Dinerstein et al. 1997, Wikramanayake et al. 1999). In this assessment, priority rankings were based habitat integrity, poaching pressure, and population status. High priority areas were identified as those where tiger populations had the highest probability of persistence over the long term. Lower priority areas were identified as those where tiger populations had a low probability of persistence over time due to small population size, isolation from other habitat blocks containing tigers, and habitat fragmentation. Because these priority rankings were based largely on secondary sources (e.g., World Conservation Monitoring Center forest maps) rather than field data for Sumatra, there is an urgent need to assess and update these maps to reflect the current status of tiger habitat and threats.

Several challenges exist to implementing a Sumatra-wide tiger GIS.

A goal of this project is to develop a conservation planning tool that can be used to support Indonesia’s efforts to identify priority tiger conservation areas and to develop a long-term conservation strategy to save Indonesia’s last wild tigers. Remote sensing using satellite images, when combined with knowledge gained from field assessments, can generate information that will enable conservation managers to prioritize where limited resources should be focused and in turn to serve as the clearinghouse for the massive amount of data that will be generated. In the field, Indonesian park rangers are already receiving training in basic census methodology and in the accurate annotation of survey maps using global positioning system (GPS) units and compasses. The Sumatran Tiger Project has developed a rapid assessment methodology (STP 1999) to enable park rangers to coordinate activities and to gather spatially-linked data in the field.

By incorporating data from satellite images we will also have the ability to monitor the environmental impact of different stochastic events. In recent years, fires have been an important source of land cover change in Sumatra. In 1997-98, a severe drought linked to an intense El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) event helped to fuel fires across the island. At Way Kambas National Park, as much as 60% of the park may have burned. By comparing land cover before and after the fire with changes in the abundance of tigers and their prey, it will be possible to develop some of the first data about the impact of fires on large mammals in a lowland rainforest in Sumatra.

Importantly, these maps will provide baseline information to monitor future changes in habitat, threats, and distribution of tigers. This is particularly important given the paucity of historical land cover information available for the island. This baseline dataset can be used to simulate different future scenarios and to help with quantitative analyses to identify principal drivers of these changes. When completed, Indonesian authorities will have access to a database that can be used to make difficult conservation decisions and updated as new data and habitat changes emerge.

We believe the impact of this project will be unprecedented in Sumatra. The Indonesian government--and forest rangers--will have access to a state-of-the-art mapping tool capable of facilitating quantitative and qualitative analysis of forest habitats and threats to tiger populations. This project will have as one of its most significant outputs information that can be used by conservation managers to prioritize where and how many tiger and other large mammal populations are to receive priority consideration.

This tiger GIS also has conservation value far beyond the tiger. Tigers historically roamed the whole island of Sumatra, and where the tiger is found, so too are many of Sumatra’s other endangered species, such as the Sumatran rhino, Sumatran elephant, primates like the orangutan, and many others. This map will be fundamentally a habitat and landscape map of Sumatra, and will provide, we hope, an additional tool for Indonesia’s conservation authorities to use to develop future ecosystem-level conservation plans for the last forests--and the last tigers--of Sumatra.

Around the world, wildlife habitat continues to be lost at an extraordinary rate. In countries like Indonesia, there simply are not enough financial or human resources to save all remaining wildlife habitat. What is urgently needed in many areas are accessible databases that researchers and conservation managers can use to collect, summarize, and apply up-to-date data to prioritize how precious conservation dollars are to be spent and to identify where these resources need to be channeled to have the most impact. We believe geographic information systems offer an important tool to conservation planners in situations like we find with the tiger in Sumatra, even where field conditions are difficult and technical literacy low. Field staff and park rangers using GPS units in the field can provide valuable data for maps that can be refined for further use in the field. These same maps can be provided to planners and managers to help identify high priority conservation areas.

We are grateful to our sponsors and counterparts in Indonesia: The Indonesian Institute of Sciences (LIPI), the Ministry of Forestry’s Directorate of Forest Protection and Nature Conservation (PKA), Taman Safari Indonesia (TSI), the director and staff of Way Kambas National Park, and staff of the Sumatran Tiger Project. This work has been funded primarily by the Save The Tiger Fund, a special project of the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation in partnership with ExxonMobil, administered through the Minnesota Zoo Foundation and The Tiger Foundation (Canada). Other conservation partners of this component of the Sumatran Tiger Project include the Zoological Society of London (U.K.), Fauna and Flora International (U.K.), South Lakes Wild Animal Park (U.K.), and Dreamworld (Australia). Their generous support is gratefully acknowledged.

CITES. 1999. Indonesia tiger conservation issues. Pages 46-50. Issues relating to species: Tiger. Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora: Forty-Second meeting of the Standing Committee, Lisbon, Portugal.

Collins, N. M., J. A. Sayer, and T. C. Whitmore, eds. 1991. The conservation atlas of tropical forests: Asia and the Pacific. Macmillan Press Ltd, London.

Dinerstein, E., E. Wikramanayake, J. Robinson, U. Karanth, A. Rabinowitz, D. Olson, T. Mathew, P. Hedao, M. Connor, G. Hemley, and D. Bolze. 1997. A framework for identifying high priority areas and actions for the conservation of tigers in the wild. World Wildlife Fund-US and Wildlife Conservation Society, Washington, D.C.

Franklin, N., Bastoni, Sriyanto, S. Dwiatmo, J. Manansang, and R. Tilson. 1999. Last of the Indonesian tigers: A cause for optimism in J. Seidensticker, S. Christie, and P. Jackson, eds. Riding the tiger: Tiger conservation in human-dominated landscapes. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Hoogerwerf, A. 1970. Udjung Kulon: The Land of the Last Javan Rhinoceros. E. J. Brill, Leiden.

Nyhus, P., Sumianto, and R. Tilson. 1999. People, politics, and village-level conservation in Sumatra, Indonesia. Proceedings of the 1999 AZA Annual Conference, Minneapolis, MN. AZA, Bethesda, MD.

Nyhus, P., R. Tilson, and N. Franklin. In press. Social and Administrative Guidelines for Field Conservation in Indonesia: Experiences from the Field. AZA Field Conservation Resource Guide. American Zoo and Aquarium Association, Bethesda.

Nyhus, P. J. 1999. Elephants, tigers, and transmigrant: Conflict and conservation at Way Kambas National Park, Sumatra, Indonesia. Unpublished dissertation, University of Wisconsin, Madison.

Seidensticker, J. 1987. Bearing Witness: Observations on the extinction of Panthera tigris balica and Panthera tigris sondaica. Pages 1-8 in R. L. Tilson and U. S. Seal, eds. Tigers of the world: The biology, biopolitics, management, and conservation of an endangered species. Noyes Publications, Park Ridge, NJ.

Seidensticker, J., S. Christie, and P. Jackson, eds. 1999. Riding the tiger: Tiger conservation in human-dominated landscapes. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, U.K.

Smith, J. L. D., S. C. Ahearn, and C. McDougal. 1999. Landscape analysis of tiger distribution and habitat quality in Nepal. Conservation Biology 12: 1338-1346.

STP. 1999. Sumatran Tiger Project Report. Sumatran Tiger Project, Minneapolis, MN.

Sullivan, P. 2000. A GIS assessment of landscape patterns in eastern Jambi Province, Sumatra, Indonesia, with implications for the migration or dispersal of Sumatrn tigers (Panthera tigris sumatrae). Department of Biology. Colby College, Waterville, ME.

Tilson, R., and P. Nyhus. 1998. Keeping problem tigers from becoming a problem species. Conservation Biology 12: 261-262.

Tilson, R., P. Nyhus, and N. Franklin. in preparation. Tiger and large mammal restoration in Asia: Ecological theory and sociological reality in D. S. Maehr, R. F. Noss, and J. L. Larkin, eds. Large Mammal Restoration: Ecological and Sociological Considerations.

Tilson, R., P. Nyhus, P. Jackson, H. Quigley, M. Hornocker, J. Ginsberg, D. Phemister, N. Sherman, and J. Seidensticker, eds. 2000. Securing a future for the world's wild tiger. Save The Tiger Fund, National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, Washington, D.C.

Tilson, R., P. Nyhus, Soemarsono, E. Sumardja, J. Manansang, A. Budiman, and N. Franklin. in press. Balancing the needs of tigers and people: From workshop to conservation action in Sumatra, Indonesia. Zoo Biology .

Tilson, R., D. Siswomartono, J. Manansang, G. Brady, D. Armstrong, K. Traylor-Holzer, A. Byers, P. Christie, A. Salfifi, L. Tumbelaka, S. Christie, D. Richardson, S. Reddy, N. Franklin, and P. Nyhus. 1997. International co-operative efforts to save the Sumatran tiger Panthera tigris sumatrae. International Zoo Yearbook 35: 129-138.

Tilson, R. L., K. Soemarna, W. Ramono, S. Lusli, K. Traylor-Holzer, and U. S. Seal. 1994. Sumatran tiger population and habitat viability analysis report. IUCN/SSC Captive Breeding Specialist Group, Apple Valley, MN.

Whitten, A. J., S. J. Damanik, J. Anwar, and N. Hisyam. 1987. The ecology of Sumatra. Gajah Mada University Press, Yogyakarta, Indonesia.

Wikramanayake, E. D., E. Dinerstein, J. G. Robinson, K. U. Karanth, A. Rabinowitz, D. Olson, T. Mathew, P. Hedao, M. Connor, G. Hemley, and D. Bolze. 1999. Where can tigers live in the future? A framework for identifying high-priority areas for the conservation of tigers in the wild. Pages 256-272 in J. Seidensticker, S. Christie, and P. Jackson, eds. Riding the tiger: Tiger conservation in human-dominated landscapes. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, U.K.