The NOAA Coastal Services Center, in conjunction with the National Marine Sanctuary Program, is currently working toward the development of digital representations of legal boundaries for all 13 National Marine Sanctuaries. While sanctuary boundaries are at present legally described using textual descriptions and geographic coordinates within the United States Code of Federal Regulations (CFR), it has been generally recognized that there is a less than adequate spatial component to this regulatory framework.

As the coastal management community attempts to translate legal boundary definitions to a digitally compatible format for integration with current technologies, a number of inadequacies, gaps, and ambiguities are revealed. Consequently, while the desire for digital representations of sanctuary boundaries has been expressed by a number of parties, the implications of their development have only begun to be examined. A number of general boundary questions, such as legal defensibility and level of accuracy, have arisen during the process of developing digital representations of sanctuary boundaries, and many of these questions remain unanswered.

Geographic information systems allow for both analysis of the legal description within the CFR and for the development of boundary mapping solutions. Several legal definitions of National Marine Sanctuary boundaries have been examined for accuracy, inconsistencies, and errors, and where necessary, revisions or clarifications of the legal boundaries have been developed. Using these and other examples, the process for creation of digital representations of sanctuary boundaries will be presented and discussed.

On May 22, 2000, President Clinton issued Executive Order number 13158 creating an expanded and strengthened comprehensive system of marine protected areas. The executive order, which directs the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the Department of the Interior to develop and maintain a national inventory of all federal, state, tribal and local marine protected areas (MPAs) in U.S. waters, has spurred a number of related activities, including projects which have the stated objectives of acquiring digital geographic boundaries for state special protected areas. While digital representations may already exist for many of these areas, a great deal of digital development may be necessary to accurately and precisely describe these marine boundaries in a manner compatible with today’s technology. An understanding of the complexities involving such representations is necessary to address many of the processes involved with managing the coastal environment.

Through the extensive analysis of national marine sanctuary boundaries, the NOAA Coastal Services Center (Center) and the NOAA Office of National Marine Sanctuaries (ONMS) have identified and addressed a number of problems and issues common to the development of marine protected area (MPA) boundaries. While it is understood that the system of MPAs currently being developed under the executive order consists of protected areas falling within a wide variety of jurisdictions, such as state, county, and tribal, many of the issues inherent in creating legal and digital boundaries are applicable across a spectrum of situations. Although there is currently no comprehensive national framework or standards for marine boundaries, the identified issues and resolutions may help government agencies and others involved in the boundary process avoid the quagmire of legal and spatial ambiguity.

While some MPAs may at present be legally defined with either textual descriptions, coordinates, or a combination of the two, it has been generally recognized that there is a less than adequate spatial component to marine boundary definitions. As the coastal management community attempts to translate legal boundary definitions to a digitally compatible format for integration with current technologies such as geographic information systems (GIS) and electronic chart display and information systems (ECDIS), it has become clear that the current formats and methodologies for defining marine boundaries have become outdated and problematic. Accurately and precisely defined MPA boundaries are needed for a number of reasons; if there are gaps, inconsistencies, and ambiguities, legal aspects of the MPA may be called into question. Problems may subsequently arise concerning enforcement, private land rights and ownership, maritime interests, resource management, and mineral extraction. Ambiguously defined boundaries allow for divergent interpretations, presenting difficulties to managers, enforcement staff, and others.

Through its work with the ONMS, the Center has gained extensive experience in the analysis and correction of existing national marine sanctuary boundaries. A significant number of issues have been identified, many of which may be common to additional areas outside the realm of this project. Consequently, suggestions for boundary development are based on the format and system used within the sanctuary program. Because of the diverse nature of the existing MPAs, some interpretation on the use and significance of the issues presented in this document may be necessary. However, issues which have been identified as being problematic in the definition of national marine sanctuaries may be the same across a variety of jurisdictions, and consequent resolutions should be applied as situations warrant.

The wide variety of boundary mapping issues and ambiguities identified through the extensive analysis of existing national marine sanctuaries can be grouped within a number of categories. The nature of many of the problems, however, dictates that some issues will be common to multiple categories. The specific examples used within each of these categorized areas, though, will illustrate problems common across the program.

The categories are as follows:

The inherent differences between legal definitions and digital boundaries are clearly demonstrated when attempting to spatially establish a representation of the shoreline boundary of an MPA. While the outer, or seaward, boundary coordinates of national marine sanctuaries are often explicitly described within the United States Code of Federal Regulations (CFR), many of the current definitions simply define the inner or shoreward boundary of the sanctuary as following the mean high-tide line. A number of problems arise from the fact that this line is ambulatory. Additionally compounding the problem is the three-dimensional nature of this line. The mean high-tide line in not actually at a uniform level, but rather is a fluctuating line that varies from point to point. Consequently, the intersection of this line with the land connects points of differing elevation and forms a vertically undulating line. So while descriptively useful and applicable in reality, depicting the line in a legally valid way for use in a digital boundary presents a number of issues.

One concern with the development of shoreline boundaries is the geospatial disparity within available data sets. While a great deal of data may be available that depicts the shoreline of the United States, large-scale NOAA nautical charts are considered to be the legal standard concerning maritime interests, and have proven to be legally defensible depictions of maritime geographic features. The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea has affirmed the validity and legality of NOAA nautical charts in their representation of the mean low-water mark. In addition, U.S baseline points, from which a number of marine boundaries such as the State Seaward Boundary are projected, are developed from large-scale nautical charts. As data from this source have been proven accurate and legal, the assertion could be made that the depicted shoreline is in fact an acceptable representation.

Providing an entirely coordinate-based boundary removes ambiguity regarding sources from which to interpret various extents of an MPA. An additional concern, however, is the translation of the chart’s shoreline to such a format. While specific technical instruction for doing this is not necessarily appropriate for discussion here, the basic key to creating a coordinate-based shoreline derived from large-scale charts is to use a sufficient amount of points to represent the line within national map accuracy standards and to maintain the accuracy and precision of the original source data. National map accuracy standards require that for maps on publication scales larger than 1:20,000, not more than 10 percent of points tested shall be in error by more than 1/30 inch, measured on the publication scale. Any use of nautical charts should be confirmed within the textual description of the MPA boundary, as well as within the accompanying metadata. Coordinates derived from nautical charts can then be later converted to a format suitable for the generation of line segments representing the same areas.

The NOAA Coastal Services Center has begun preliminary development of digital representations of the shoreward boundary for several sanctuaries. The length and location of many of the sanctuaries’ shorelines dictate that a number of different sources (mainly nautical charts) are used. Consequently, inner boundaries are not developed as a single line segment, but rather a combination of a number of segments. Each of these segments has been attributed to reflect precise information describing the source. Documenting these segments in such a manner will allow for future revisions, without affecting the entirety of the boundary. In addition, by including a full and accurate description of attribute fields within the accompanying metadata, the utility of the digital boundary will be preserved.

The example below (Figure 1) shows a highlighted line segment from the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary. The identified attributes for this segment include the segment number, the feature from which the line segment was generated, the type and name of the source used (in this case a nautical chart), the date and edition of the chart, and the scale of the chart. In addition, to facilitate future revision and examination, the beginning and ending geographic coordinates of the line segment are identified. Presumably, if boundary revisions were necessary in this area, changes could be made to this individual segment while preserving the status of adjacent boundary components.

Figure 1. Line segment from draft Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary digital boundary.

In this context, imprecise and inaccurate coordinates are defined as geographic points of a boundary whose intended location is discernable, but whose placement in relation to features, either components of or adjacent to the boundary, demonstrates their misplacement. While in some situations the intended location of the boundary coordinate may be questionable, textual descriptions often allude to their correct or precise placement. There are several occurrences of this within the national marine sanctuary legal descriptions. One example of a textual description alluding to the intended location of boundary coordinates is found in the situation involving the adjacent boundaries of Cordell Bank National Marine Sanctuary (CBNMS) and the Gulf of the Farallones National Marine Sanctuary (GFNMS). The CFR boundary definition states that the CBNMS boundary runs along the boundary of GFNMS. In fact, those familiar with the sanctuaries have interpreted the boundary to be shared. However, when both sets of coordinates from the two sanctuaries are plotted, they do not coincide (Figure 2). Consequently, a sliver area exist between the two sanctuaries that could be interpreted to fall outside the jurisdiction of either area.

Figure 2. Cordell Bank and Gulf of the Farallones National Marine Sanctuaries.

Another situation involving imprecise and inaccurate coordinates is found in the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary (FKNMS). Here, the boundary of the proposed Tortugas North Ecological Reserve extends beyond the limits of the outer boundary of the FKNMS. In addition, another coordinate defining the same area appears to be incorrectly placed, falling well south of the outer sanctuary boundary (Figure 3). This apparent misplacement was discovered after comparisons were made of the listed coordinates with a depiction of the area on a draft designation document. Comparisons of these interpretations, as well as consultations with sanctuary staff and others familiar with the area, have clarified the intent of the original designation. While solutions to such problems may involve as little as simply moving the coordinates in question, analysis prior to official boundary designations will avoid the problems associated with such changes after the boundary has become legal.

Figure 3. Tortugas North Ecological Reserve.

Both of the situations described above were addressed by redefining several coordinates to coincide with adjacent boundaries. Regarding the situation with the adjacent boundaries of CBNMS and GFNMS, it was determined that because GFNMS had been designated and established first, it would be appropriate to move the coordinates from CBNMS to coincide with GFNMS. In addition, four additional coordinates were added to the CBNMS boundary to clarify the coterminous nature of the two boundaries. However, changes such as this require precise documentation. This was accomplished through both the accompanying attribute table associated with the boundary point coverage, and through additional descriptions within the associated metadata. For each of the individual boundary points, an exact geographic position was provided within the attribute table. In addition, the previous location of the boundary point was given, as well as a coded description of the "history" of the coordinate, describing whether the coordinate was moved or added to the definition. The source coordinate from which the new location was derived is also described. This information is necessary in accounting and justifying for these changes, as well as providing an accurate and detailed lineage of the sanctuary boundary.

The situation with the FKNMS involved the same type of changes and documentation. Here, several boundary coordinates for the Tortugas North Ecological Reserve were adjusted to coincide with the outer boundary described for the FKNMS. Additional coordinates were added to the outer boundary as well to coincide with those of the ecological reserve. As with the situation involving the CBNMS and GFNMS boundaries, a precise accounting of boundary changes was provided in both the attribute table and associated metadata.

Textual and geographic conflicts occur when there are differing accounts of the location of the MPA within the definition. These situations are typically the result of conflicts between the textual description and the listed geographic coordinates. For example, the CFR definition for CBNMS states that the boundary runs "to the 1,000-fathom isobath northwest of the Bank, then south along this isobath to the GFNMS." The boundary coordinates, however, fall well short of this isobath line as depicted on large-scale charts of the area (Figure 4). Because of this, there are two conflicting accounts of the western boundary of the sanctuary; the boundary can either follow the isobath line or the coordinates. Of additional concern is the use of an isobath description without providing a specific source for the data. Using an isobath (sometimes called a depth curve or contour) as a boundary can be problematic. Isobaths are derived by interpolating between depth soundings. Depending on the algorithms used, subsequent calculations of the line could be different. If new data are introduced, the line could change. It is recommended that the isobath line (with chart source) be used only as a general description, and that coordinates be provided for the precise area designation.

After consultations with sanctuary and enforcement personnel associated with the sanctuary, it was determined that the textual description for the CBNMS boundary should be changed so that it generally references the isobath line, without describing the boundary as running to or along a specific bathymetic contour. The geographic coordinates then become the overriding and specific depiction of the boundary.

Figure 4. Cordell Bank National Marine Sanctuary.

Another example of a textual and geographic conflict is found in the CFR boundary definition for Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary (SBNMS). Here, the definition states that the boundary ". . . follows a line contiguous with the three-mile jurisdictional boundary of Massachusetts." The jurisdictional boundary of Massachusetts could be interpreted several different ways, as there are two developed boundaries depicting this extent. The State Seaward Boundary, defined by the United States Department of the Interior's Minerals Management Service (MMS) is calculated from the fixed baseline used for the Submerged Lands Act boundaries and deals primarily with state claims to resources. The 3-mile Limit Line begins the extent of Federal jurisdiction of the Territorial Sea and is calculated from the ambulatory baseline. Consequently, this line itself can move over time. In many locations, the State Seaward Boundary and the 3-mile Limit Line are identical. But because of the discrepancies between these lines near SBNMS and the listed coordinates, there could be a minimum of three different interpretations of the sanctuary boundary (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary.

In several situations, the intended geographic location of the sanctuary is clear, but the description of the area is in error. The CBNMS is described within the CFR textual description as ". . . extending at 180 degrees form the northernmost boundary of the [GFNMS]." The plotted coordinates of the sanctuary extend in a west-southwesterly direction from the GFNMS boundary, or roughly 250 degrees from the northwesternmost point. However, 180 degrees is in a southerly direction, and drastically different from the boundary’s intended direction and location. Because of the widely known and undisputed general shape and location of the sanctuary, these conflicting accounts have never seriously impeded interpretations of the boundary, but nonetheless may present ambiguities to those unfamiliar with the spatial characteristics of the sanctuary.

Coordinate omissions and errors exist where coordinate locations are either clearly wrong or missing entirely from the definition. While this categorization is rather self-explanatory, several examples from the national marine sanctuary program clearly illustrate the problem and highlight the range of difficulties in rectifying the situation.

For the first example, the Great White Heron National Wildlife Refuge’s boundary, located within the boundary of the FKNMS, is described within the legal CFR description of the sanctuary. However, the placement of one particular coordinate alludes to the possibility that it may be an incorrect listing resulting from a typographical error within the CFR. The latitude of the coordinate is currently listed as 24 degrees 48.0 minutes North, when in fact it is thought to be 24 degrees 40.8 minutes North, based on the trend of the boundary (Figure 6). The solution for this problem may be as simple as confirming the location with the appropriate agency.

Figure 6. Great White Heron National Wildlife Refuge.

A more serious problem was encountered during the analysis of the boundary definition for the GFNMS. Here, no northern intersection of the sanctuary boundary with the shoreline is defined within the CFR or described within the listed boundary coordinates. The coordinates listed for the GFNMS begin at coordinate 1, located approximately six nautical miles offshore, and continue until their terminus at the southern boundary’s intersection with the shoreline. However, because no coordinate is listed to define the northern intersection with the shoreline, the currently defined boundary does not form a closed polygon (Figure 7). This raises serious problems relating to many aspects of the sanctuary, including enforcement and management.

Figure 7. Gulf of the Farallones National Marine Sanctuary.

Referencing external data not immediately available within the CFR definition is by far the most ubiquitous problem inherent in sanctuary boundary location. In many situations, a listing of coordinates is used to define the outer or seaward boundary of the site. However, additional components of these definitions are often dependent upon unavailable or not easily obtainable external data. This compounds the possibility for error and varying interpretations stemming from inaccuracies and differences within these data or referenced boundary descriptions of adjacent jurisdictions. Much of the digital data available depicting these areas has a rather nebulous lineage, epitomizing the need for appropriate metadata. The best possible method for interpreting referenced external boundaries would be to acquire a legal description of these areas and incorporate derived coordinates within the MPA description. However, at least in the case of national parks, many of the official and "legal" descriptions of park boundaries are the original survey maps, the location and acquisition of which is problematic. Defining adjacent boundaries is made additionally difficult considering the marine environment where many of these areas are located, as marine boundaries are not generally demarcated with fence rows, signs, or landmarks.

Problems stemming from the dependence on external data are typified by the situation with the FKNMS, where national park boundaries are used in several areas to define sections of the sanctuary. The FKNMS boundary is described as beginning "at the northeasternmost point of Biscayne National Park located at approximately 25 degrees 39 minutes north latitude, 80 degrees 5 minutes west longitude." When plotted on a nautical chart showing the boundary of Biscayne National Park, however, this initial coordinate for FKNMS does not coincide with that which is depicted on the chart. In addition, an ArcView shapefile of the park, available on the National Park Service GIS Web site, differs in location from both the nautical chart and the described coordinate for FKNMS. In fact, the CFR-defined beginning coordinate is approximately 730 meters northeast of the corner of the park depicted by the shapefile (Figure 8). The ambiguity of the national park boundary data has also brought into question other adjacent areas of the sanctuary. The nature of this conflict demonstrates the importance of cooperation between government agencies. Because of the extent of the nebulous sections of the boundary, the sanctuary cannot be defined without knowing the precise location of the park. However, it is conceivable that both agencies could participate in determining mutually acceptable coterminous boundaries, defining such with geographic coordinates. The alternative scenario of using uncertain park boundaries to derive a coordinate-based definition of the sanctuary could lead to future problems if the national park were to determine a conflicting boundary at a later date.

Figure 8. Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary.

Problems interpreting or acquiring external data are not limited to issues with national park boundaries. The coastal boundary of the Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary (MBNMS) is currently defined within the CFR as the mean high-water line excluding certain bodies of coastal waters. International Collision at Sea Regulation (Colreg) lines are used within the definition to describe these exclusions. Colreg lines were developed by the Inter-Governmental Maritime Consultative Organization (IMCO), which was later renamed the International Maritime Organization. Colreg demarcation lines delineate those waters upon which mariners must comply with the inland and international rules of navigation. However, no coordinates delineating these lines are listed within the sanctuary boundary definition, and thus, interpretations are again subject to data outside of the realm of the CFR definition. While for the most part, Colreg lines are clearly represented on nautical charts (Figure 9), they are defined and maintained by the United States Coast Guard and are subject to change, both in geographic location as well as in nomenclature. As a result, boundary definitions that are dependent upon these lines may in fact be interpreted differently, but perhaps accurately by law.

Figure 9. International Collision at Sea Regulation (Colreg) Line.

The addition of several coordinate points enhances the definition of these boundary lines. In the development of the inner boundary for the MBNMS, Colreg lines from nautical charts existing at the date of designation of the MPA were used to establish these coordinates. However, while points generated based on Colreg lines should be documented within accompanying metadata, the specific dependence upon a particular Colreg line within boundary definitions should be avoided. This will serve to avoid confusion and ambiguity should a line be moved.

A number of examples of the dependence upon external data are present in the CFR definition of the Olympic Coast National Marine Sanctuary (OCNMS). The coastal boundary of the sanctuary is defined as "the mean higher high water line when adjacent to Federally managed lands cutting across the mouths of all rivers and streams, except where adjacent to Indian reservations, State and county owned lands; in such case, the coastal boundary is the mean lower low water line." Accurate and precise shoreline and inner boundary definitions become additionally difficult as a consequence of the variation of tidal datums required. Specific and accurate delineation of federal, state, county, and tribal lands must also be obtained prior to mapping or determining the inshore boundary of the sanctuary. The level of precision on currently available boundaries depicting these jurisdictions do not coincide with the shoreline as represented on various nautical charts of the area, presenting serious difficulties in the translation of the boundary definition into its digital equivalent.

Many of the national marine sanctuaries are bounded by a river or stream. In a number of situations, sanctuary boundaries and jurisdictions extend up these rivers. This becomes problematic due to the fact that the jurisdictional inland extents of rivers within some sanctuaries are often not defined within the legal description, but often enforced based upon interpretations of sanctuary personnel. The delineation of the inland jurisdictional extent of rivers and streams, as well as the process for delineating boundaries cutting across their mouths, may present the possibility for divergent interpretations of boundaries. The accuracy with which a boundary is mapped in these situations is often dependent upon the scale with which the data are analyzed. Using GIS to "zoom in" on digital charts or other data at scale significantly different from that in which they were developed may not be appropriate, as accuracy and precision are tied to the original map scale, and will not improve as the user zooms in. However, GIS has also allowed for the use and analysis of large-scale imagery or other data not previously available. Where the definition may have been appropriate at the time of designation, the ability to closely examine geographic areas in relation to the defined boundary has highlighted the need for more precise interpretations.

The definition for the OCNMS describes the boundary of the sanctuary as "cutting across the mouths of rivers and streams" when adjacent to federal lands. However, a precise description of how exactly the boundary line is to do this remains undefined. Many of the river mouths represented on nautical charts are wide enough to allow for several scenarios of where the boundary might depart one riverbank and intersect the adjacent riverbank (Figure 10).

Figure 10. Mouths of Rivers and Steams in the Olmpic Coast National Marine Sanctuary.

The GFNMS is also characterized by the presence of several rivers that are included within the jurisdiction of the sanctuary. While sanctuary staff have indicated the inshore extent of the boundary in these areas, there is a concern regarding the ambulatory nature of the rivers, as well as variations caused by the fluctuation of river levels. However, based on experiences here and with other sanctuaries, a process has been developed to delineate these extents. Here, two coordinates are placed on opposing sides of a river, at a sufficient distance from the river itself so as to avoid geomorphologic process or other factors which may affect the placement of the boundary. The jurisdiction of the sanctuary is then represented based on the points where this line intersects the banks of the river (Figure 11). This will allow for movement of the river and the fluctuation of water levels, and will ensure that the inland extent of the boundary will be sufficiently delineated over a period of time.

Figure 11. Inland Extent of Gulf of the Farallones National Marine Sanctuary.

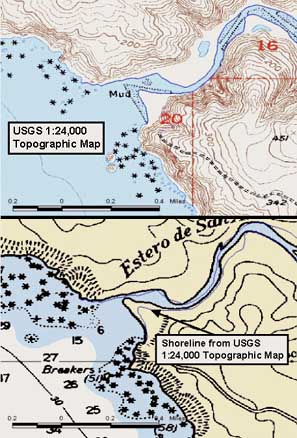

The development of MPA boundaries based on the depiction of rivers presents a number of other difficulties as well. Many NOAA nautical charts fail to depict the inland extent of rivers, but often only show the mouths. However, while these areas are often accurately represented on United States Geological Survey (USGS) 1:24,000 topographic maps, those areas that are represented on both sources often do not match exactly. This is demonstrated below, where the shoreline of a river as depicted on a USGS map is overlaid on a nautical chart (Figure 12). Because of such discrepancies, it becomes necessary to determine the source (or combination of sources) from which to derive the boundary. This process may be best addressed on a case-by-case basis, with personnel familiar with the area making those determinations as to which data source best corresponds to the true location of the shoreline in question. As was discussed previously, individual line segments should be clearly attributed with source information within associated data tables and metadata.

Figure 12. Differing Interpretations of Estero de San Antonio.

The MPA program described in Executive Order number 13158 will comprise a vast array of ecological and geographic areas, with a complex system of jurisdictional representation. Boundaries defining many of these MPAs will lie adjacent to other boundaries already defined, such as county, state, territorial, and international boundaries, as well as other MPA boundaries. Due to the extent by which boundary descriptions and geographic settings of MPAs can vary, defining a generalized step-by-step guide to the analysis and correction of MPA boundaries is not appropriate, as each of these analyses will need to focus on specific details and situations relevant only to that MPA. However, based on experiences and lessons learned from previous work with the national marine sanctuaries, a number of recommendations are suggested here to serve as a guide when examining boundaries of existing MPAs.

Because of the many ambiguities and inconsistencies within MPA descriptions, as well as the potential for conflicting interpretations outside the realm of the legal definition (if one exists), a necessary first step in the process is the spatial analysis of the boundary description or definition. In order to do this accurately, any listed coordinates should be generated into a digital representation. For an accurate portrayal of the coordinates within a GIS, particular attention must be paid to retaining the original and intended precision. This is essential when coordinates are converted from degrees/minutes/seconds to decimal degrees.

During the generation of digital coordinate points, the user must also define the horizontal datum. If it has been omitted from existing descriptions of the boundary, it should then become a priority to ascertain the original intent. In some cases, the date of designation can give a clue to the correct datum. Additional boundary information can usually be obtained by contacting management personnel associated with the MPA, those involved with the original or past boundary designations, or through comparisons of datums using GIS analysis. It will become a necessary subsequent step, though, to formally designate a horizontal datum within any revised boundary definitions.

While many boundary inconsistencies and errors within MPA legal descriptions may be well known already by those familiar with the area in question, an in-depth analysis of the coordinates in comparison with adjacent landscape features, bathymetric data, and other boundaries is necessary to identify the common errors, ambiguities, and inconsistencies previously discussed. A valuable resource in the examination of the MPA boundary in relation to adjacent geographic features is NOAA nautical charts. Digital versions of these charts are available from BSB Electronic Charts, and are licensed under a cooperative research and development agreement with the National Ocean Service branch of NOAA. Depending on the size of the MPA in question, several charts may be required, and the chart used should be the largest scale available for the area. Using GIS, the coordinate points generated from the description should be overlaid on the chart. Other significant data layers should also be incorporated into the GIS. These data may include state, county, and national parks and seashores, adjacent MPAs, wildlife refuges, and any other features that may have a bearing on the boundary definition of the MPA in question. It is necessary that these data be accurate, with a full Federal Geographic Data Committee-compliant metadata record if at all possible. This becomes additionally important if these data contain features or coordinates that are referenced within the existing MPA boundary description.

Because of the unique boundary situation with the multitude of existing and proposed MPAs, it is expected that additional issues may become apparent as each undergoes an in-depth analysis. In addition, it should be assumed that additional boundary issues may also be identified through consultations with MPA personnel. However, the boundary should nonetheless be examined for the consistently prevalent issues discussed.

A significant lesson learned during the boundary analyses of national marine sanctuaries was the value and utility of those with a firsthand knowledge of the individual sanctuaries. To facilitate resolution of sanctuary boundary issues, meetings were held with personnel associated with these sanctuaries who have an intimate familiarity of the area and of the issues involved. This included enforcement and permitting personnel, sanctuary managers, research coordinators, GIS analysts, and others. In each case, NOAA General Counsel was consulted regarding legal implications related to the boundary description. These meetings were held on-site at the sanctuaries. Enlarged and large-scale maps clearly depicting the boundary issues were developed prior to these meetings, and were clearly helpful in the facilitation of discussions. In addition, nautical charts, USGS topographic maps, and other ancillary data were also available for reference.

While gaps, ambiguities, and other issues relating to the development of MPA boundaries have become well known to those directly involved in the management, enforcement, and mapping of these areas, the inherent and systematic problems associated with these marine boundaries are still not well known among many others who are inextricably linked to the process. Thus, while methods and protocols may one day be a standardized process, a more immediate need is to make those involved with MPAs acutely aware of the issues and implications of inadequately defined boundaries. Consequently, the identification of all of those currently linked to the establishment and definition of these areas, and the communication of the inherent problems, should become a primary concern.

The recent creation of a Marine Boundary Working Group (MBWG) may help to address a number of difficulties inherent in the creation of marine boundaries. Some of the issues currently being addressed by the MBWG include determining responsible parties for maintaining and distributing marine boundaries within various agencies, examining problems and issues with defining the absolute legal documentation of boundaries, and the development of standards for the creation of marine boundaries. This multiagency committee includes representatives from the Minerals Management Service, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the National Park Service, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the Federal Communications Commission, The U.S. Navy, the U.S. Coast Guard, the Bureau of Land Management, the Environmental Protection Agency, the U.S. Department of State, and the U.S Census Bureau.

It must be recognized that legal boundary definitions can no longer be seen as independent from the digital boundary development process. That which is described textually or by coordinates must represent the reality that exists in the most accurate, precise, and practical manner available. Failure to do so may weaken enforcement and management capabilities in these areas, thus delegating the MPA to a less protected status than originally envisioned. However, by recognizing the need for programmatic changes concerning the development of MPA boundaries, the level of protection of these areas may be enhanced, rendering the goals and objectives of their initial designation more valuable and enduring.

Andrew C. Hulin

Technology Planning and Management Corporation

NOAA Coastal Services Center, Charleston, South Carolina

andrew.hulin@noaa.gov

Cindy Fowler

U.S. Department of Commerce

NOAA Coastal Services Center, Charleston, South Carolina

cindy.fowler@noaa.gov

Mitchell Tartt

NOAA Office of National Marine Sanctuaries, Siver Spring, Maryland

mitchell.tartt@noaa.gov