Integrating Environmental Monitoring Data into GIS for the World Trade

Center Emergency Response

Harvey Simon and Mark Gallo, United States Environmental

Protection Agency (EPA) Region 2

In the aftermath of the September 11 World Trade Center Disaster, the EPA was

responsible for collecting, analyzing and interpreting a wide variety of

environmental data to make decisions about worker safety protection and public

health. This paper describes the process of creating a monitoring

database, integration of monitoring data into GIS during a crisis, and how data

processing procedures evolved to streamline the flow of information from field

collection and laboratories into data analysis systems to support decision

making.

Introduction

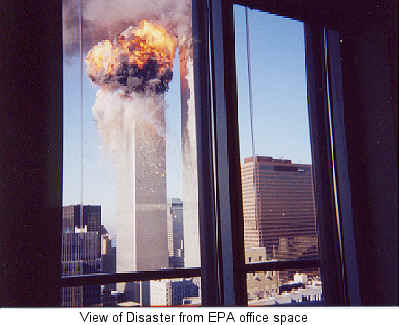

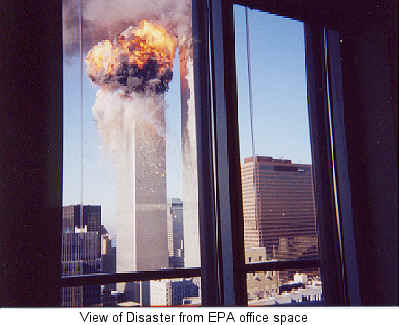

On

the morning of September 11, 2001 Region 2 employees watched in horror as the

WTC burned. Few saw both planes hit the buildings, but most were watching

when the second plane struck. Employees quickly evacuated the Region 2

main office at 290

Broadway, less than six blocks from the World Trade Center (WTC). They were on the streets when the towers fell. The evacuation

was rapid. People grabbed their things and left as quickly as possible. Computers, printers, and

other electronic devices were left running. Although frightening, the evacuation

was remarkably orderly. Employees went their separate ways outside the building,

making their ways home under difficult conditions. Within hours Region 2

emergency operations were responding to the scene.

|

(Photo Credit: John Ciorciari

http://www.geocities.com/ccng2/wtc_02.html) |

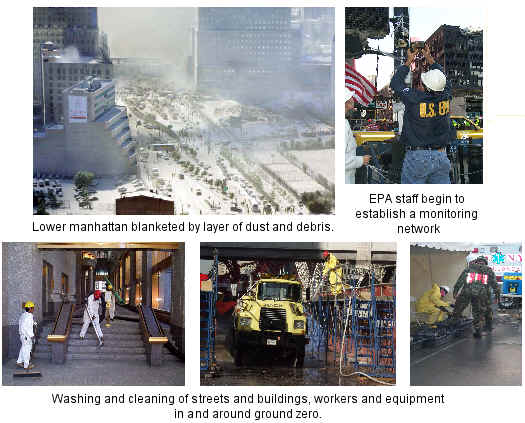

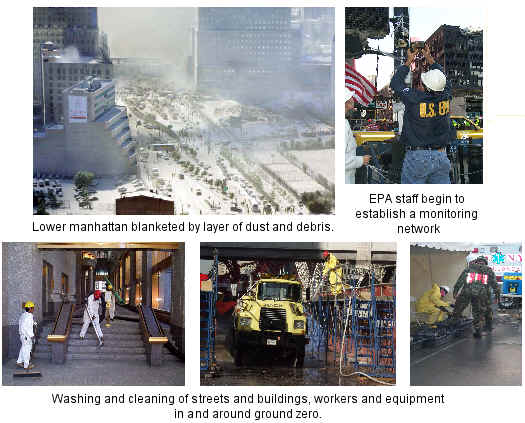

| The collapse of the World Trade Center created the need for

a coordinated emergency response effort unlike any that EPA had experienced

before. When the towers fell, lower Manhattan was coated in a thick layer of

dust and ash. The fires filled the air with acrid smoke. Region 2 responded

by vacuuming streets and buildings, decontaminating workers and equipment at

ground zero, and monitoring the dust, air and water in and around ground

zero. Sampling teams were sent into the field to monitor the air in Brooklyn

neighborhoods where the massive plume from the WTC site was drifting. |

(Photo Credit: EPA Emergency Response Staff)

Air samples were also collected from sites in New Jersey across

the Hudson River from the WTC. EPA On-Scene Coordinators (OSCs) went near Ground Zero, to survey the environmental damage and

collect bulk dust that had been dispersed all over as the towers collapsed. The air

and bulk samples were quickly delivered by car to private laboratories and the

Emergency Response Team's laboratory in Edison; the results were obtained overnight, providing

valuable information on the types and levels of contaminants that had been

released so the health of thousands of rescue workers and those residents in the

surrounding communities could be protected. Extensive monitoring for

asbestos, particulates, metals, and organics was maintained in lower Manhattan,

and at more remote sites in the five boroughs and New Jersey from the first few

days of the disaster until the site was cleared in late June, 2002.

Monitoring at the Staten Island Landfill, which was used as a storage point for

debris from the site to sift for remains and evidence, is still ongoing.

|

|

|

|

|

| Primary

monitoring activities were in downtown Manhattan and the vicinity of

the Staten Island Landfill, although there were many additional

regional sampling sites in the five boroughs and New Jersey. |

Region 2's GIS operation was thrown into disarray by the attack. The

central GIS Team was based in EPA's New York Office and most Team members were evacuated

on the day of the attack. Regional GIS and information

technology staff that had been evacuated from the New York office on the day of

the attacks managed to contact each other and arranged to work out of the

Region's laboratory in Edison, NJ where regional emergency operations had been

established. Within several days of the attack, they were providing full

time support to Mark Gallo, the emergency response data management and GIS lead.

Several members of the GIS Team were at an EPA GIS Work Group meeting in San

Francisco on the day of the attacks, and had to find their way home in the middle

of a national air transportation crisis. One managed to fly home eventually,

while the other two (including one of the authors) drove back by rental car.

The New York office was closed for the first few weeks, and telephone, Wide Area

Network and Internet Access were unavailable or limited for an additional 7-10

days. By luck, a mirror of all the Region's GIS data and applications had

been maintained at the Edison Laboratory for several years - the purpose of this

mirror was to improve performance for users in Edison, not for continuing

operations in a crisis. EPA GIS operations for the World Trade Center were

based entirely in Edison until the New York office was fully functional.

Data Management Challenges

As the EPA response to the disaster evolved, it became clear that there were

huge data management challenges that had to be resolved:

- Need for rapid, near-time processing of data for operational decisions,

worker safety and public information: In addition to requiring rapid

processing of data to support operational and public health decisions, EPA

senior management decided very early on that monitoring data would be

published via the Internet in as close to real time as possible. This

was an unprecedented activity for EPA.

- Multiple organizations collecting data, need for central clearinghouse:

Many other organizations were also collecting data for the response and New

York City requested that EPA develop a multi-agency database to store and

share the information. EPA agreed to take on this role and was

responsible for distributing data and data products to responding

organizations and the public.

- Data from different agencies in multiple electronic formats and hard copy:

Many other organizations were also collecting data for the response and New

York City requested that EPA develop a multi-agency database to store and

share the information. Data were initially provided in a wide variety of

formats from paper to electronic spreadsheets, often with almost no metadata

or background information.

- EPA data processing initially hard copy driven and not standardized: In

the early stages of the response data were being delivered in hard copy format

and entered into the database by hand, a laborious, error prone and time

consuming process.

- Need for definition of cartographic product and data report requirements

for a variety of uses: Many of the responding organizations, including EPA

were “disconnected” while working in the field, and many local resident had no

phone service or Internet access for extended periods of time. Production of

hard copy maps and reports that effectively summarized data was vital to field

work and communication with the public.

- Need for accurate base map, remote sensed and operational data: New York

City's Emergency Operations Center (EOC) was destroyed the day of the attacks,

but was re-established on a pier along the Hudson River within 48 hours of the

event. Region 2 staff obtained critical base map information from the EOC

mapping center to ensure that EPA was working from the same base information

as other responding agencies.

- Need for effective internal and external data coordination: The

overwhelming amount of data, coupled with the need for rapid and effective

dissemination to responders, managers and the public made effective

coordination critical.

Data Management and Geospatial Support

Managing and Georeferencing Environmental Data

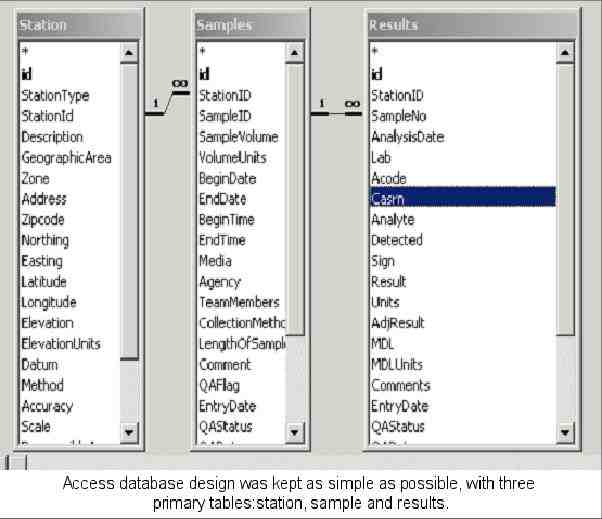

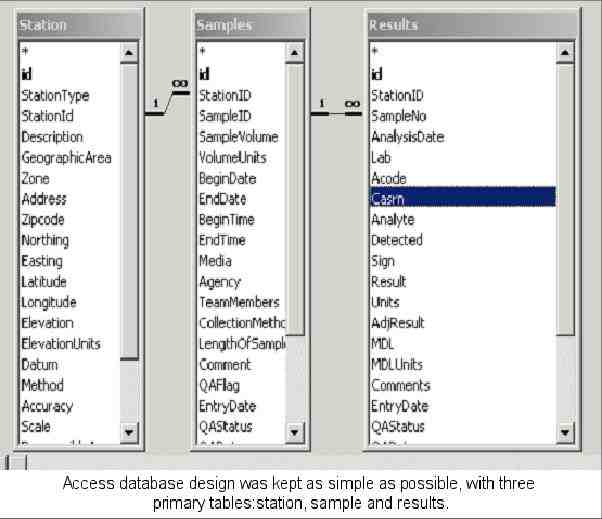

During the first few days following the attacks, Regional GIS and IT staff developed a

Microsoft Access database to house all EPA monitoring data that was being

processed by contract labs, acquired critical local data from New York City

agencies working out of the Emergency Operations Center on Manhattan's west

side, and established geocoding procedures in ArcView for monitoring locations and

incorporations of locational information into the database. In the early stages

of the response, data were being delivered in hard copy format and entered into

the database by hand, a laborious, error prone and time consuming process. The

Region 2 GIS Team developed automated procedures for data entry that radically

reduced errors and data entry work effort.

Many other organizations were also collecting data for the response and New

York City requested that EPA develop a multi-agency database to store and share

the information. EPA Office of Environmental Information (OEI) and OEI Systems Development (SDC) contract staff developed this database using the Region 2 Access

database as a model within less then a week of this request. This required SDC

staff to design, develop and implement a database management operation capable

of tracking the results of environmental monitoring being conducted by 13 city,

state, and federal agencies at the World Trade Center site. The system provided

a front end interface with a wide range of search options and provides standard

reports as well as download capabilities. SDC staff designed data entry

templates and worked with the relevant organizations to facilitate the

collection of their data into the system in whatever way was most efficient. At

times this involved painstaking manual data entry of monitoring results from

organizations who had lost their electronic connectivity – could not upload data

results into a database - and were operating in "paper and fax" mode to submit

their sampling results. In all, information from hundreds of monitoring sites

covering a broad range of media and substances was entered into the database

and made available for analysis and decision-making to Agency and City

officials. Access to the Multi-Agency Database was provided through

a web interface developed by OEI which allowed EPA staff and participating

agencies to easily extract data.

Web Delivery of Monitoring Results to Public

On the heels of the delivery

of the WTC monitoring database was the challenge of providing public

access to real-time status of monitoring results around the WTC. OEI developed

procedures for incorporating data from the multi-agency database into public

access web pages. A team of OEI, Region 2, Office of Air Quality Planning

and Standards (OAQPS) and SDC staff collaborated in the

development and delivery of a series of WTC data presentations – posted on EPA's

Homepage beginning in early October - that provided users with detailed

information on monitoring results at the WTC and the surrounding environment. These

data presentations incorporated detailed maps of monitoring locations, utilizing

base data layers provided by New York City, data tables showing specific

monitoring results and incorporated context developed by EPA experts for public

dissemination. To assure the data was kept as current as possible, an automated

process was put in place to update the website presentations as the database

itself was updated each day. This way, the public had access to the most current

data in the database as it was received and EPA website statistics show that

these materials received hundreds of thousands of hits over October and

November. This was EPA's first attempt at near real-time delivery of emergency

response sampling. (see http://www.epa.gov/wtc/).

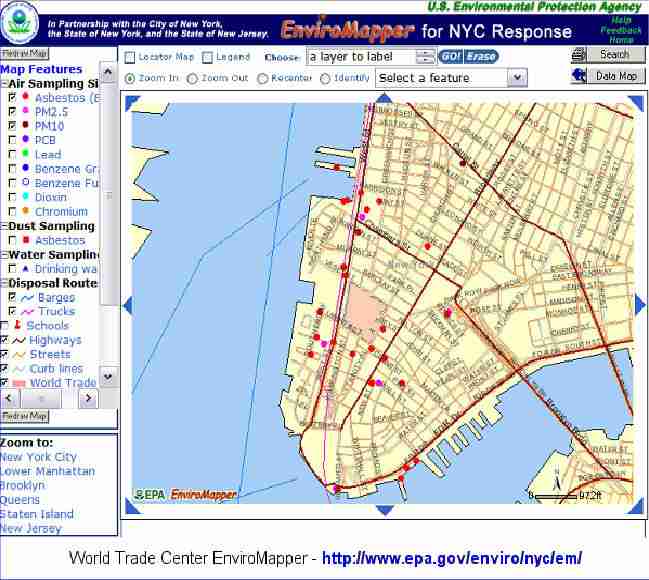

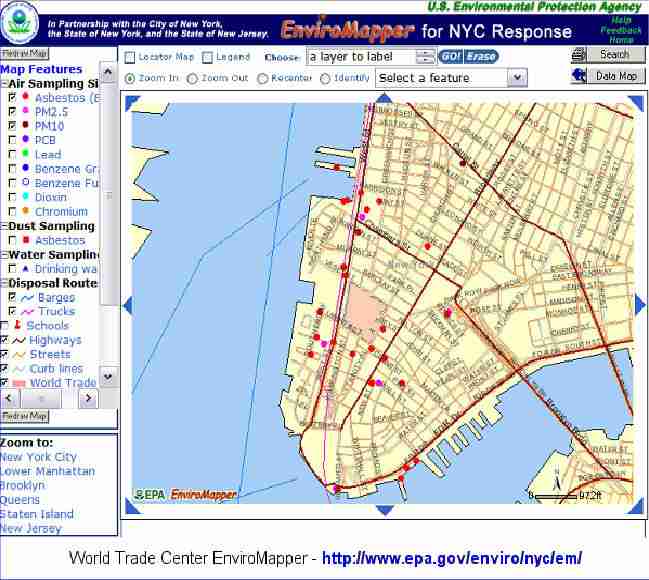

To assure that web site users had a fully integrated view of the monitoring

activities surrounding the WTC, the OEI/SDC Geospatial Team designed and

developed a customized EnviroMapper for NYC Response utilizing ArcIMS. Building on the success of

EPA's existing EnviroMapper applications, the NYC Response EnviroMapper

provides a sophisticated interactive mapping interface that allows the user to

select a geographic area and receive back a map that shows where environmental

monitoring was conducted in the selected area, the type of monitoring done and

the results that were found. (see

http://www.epa.gov/enviro/nyc/em/)

Development of Data Summaries, Trend Analysis and Cartographic Products and

Disseminating Information to EPA Staff and Cooperating Federal, State and Local

Agencies

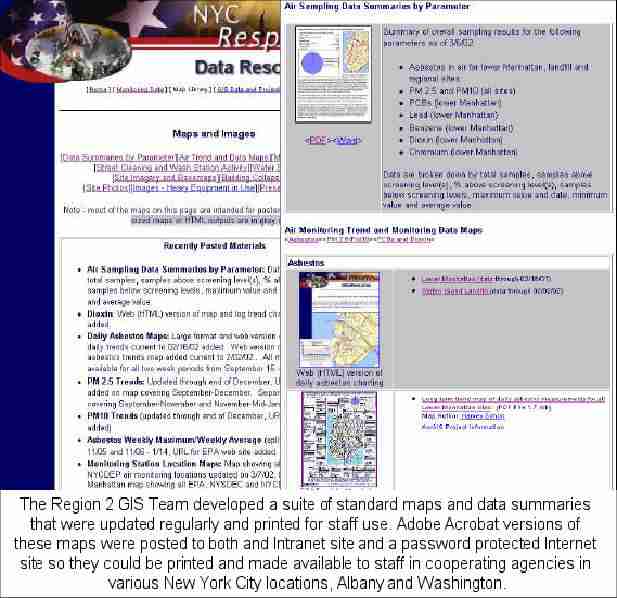

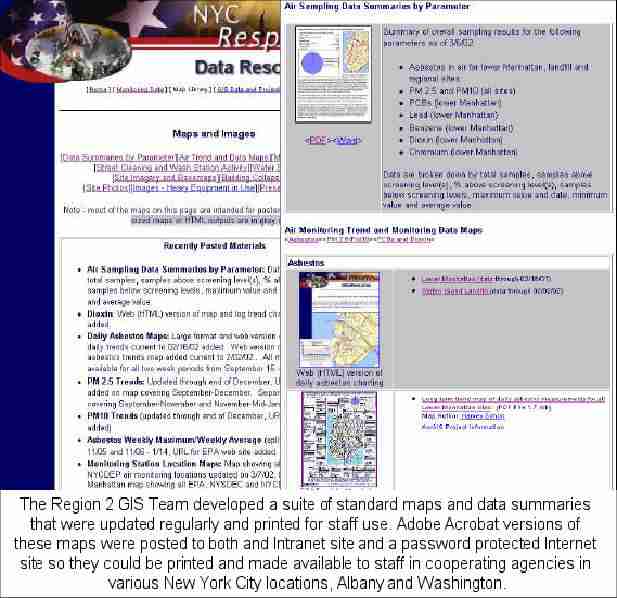

One of the telling aspects of this crisis was the impact on

telecommunications. Many of the responding organizations, including EPA were

“disconnected” while working in the field, and many local residents had no phone

service or Internet access for extended periods of time. Production of hard copy

maps and reports that effectively summarized data was vital to field work and

communication with the effected public. The Region 2 GIS Team developed a suite

of standard maps and data summaries that were updated regularly and printed for

staff use. Adobe Acrobat versions of these maps were posted to both and Intranet

site and a password protected Internet site so they could be printed and made

available to staff in cooperating agencies in various New York City locations,

Albany and Washington. These outputs were used at dozens of small and large

internal, interagency and public meetings, (including Senate and New York City Council

hearings) to explain air quality conditions and trends. Many of these outputs

were developed in cooperation with New York City Department of Health staff

involved in risk communication.

Lessons Learned

This incident stretched EPA's and other government organizations resources in

unprecedented ways. Based on our experience in dealing with data

management and geospatial support, a number of lessons learned became apparent,

many of which could provide useful guidance to any organization trying to

prepare for large disasters or dislocations.

Disaster Recovery, Failover and Backup

- You might be at the center of a disaster and need to be able to protect

your staff and offices, and get back in operation swiftly:

- Develop individual office Emergency Response Plans which will itemize

those critical functions that need to be provided and how to accomplish

these tasks should we be unable to use our offices.

- Develop a telephone and e-mail contact list for all members of the staff

which would be published in “paper” and through a secure web site available

to authorized users. In addition, develop a contact list for those that we

would need to keep in contact with in future events (i.e., other Federal,

state and local governments, grantees, vendors, etc.).

- Establish back-up plans for continuing critical work functions should an

office be unable to continue its operations. Develop plans that would

permit business continuing should an office be down or were unable to gain

access to various Agency and Regional automated systems – Develop a

telephone cascade plan so that information can be moved from employee to

employee. Home phone, cell phone and e-mail contact information for key

employees with emergency response roles.

- Establish web sites and off-premise automated telephone systems that

would provide information to both staff and others needing to re-establish

communications with EPA. – Consider telephone service from several Central

Offices, rather than just one. Using more than one vendor does not guarantee

they are not using the same physical network - you must verify and ask the

right questions of service providers.

- Supplement digital telephone service with analog for emergency purposes.

- Cell phones, wireless and web-based e-mail critical assets.

- Non-emergency security procedures may hurt you in a crisis, plan for

flexibility when trying to re-establish operations..

- Plan for alternate locations which can accommodate large numbers of

staff, including the necessary voice, data, and e-mail infrastructure.

- Mirror all critical data and applications at disaster recovery

location(s).

- Maintain a good relationship with your hardware and software vendors.

Vendor flexibility and support during the crisis were invaluable.

Esri, for example, provided tremendous support to New York City in

establishing it's Emergency Mapping Center, and responded quickly to give

Region 2 temporary ArcGIS licenses for new machines installed in the Edison

Laboratory.

Data Management, Data Analysis and Information Product Development

- Maintain IT capabilities and infrastructure: Veteran staff and contract

support with broad skills, flexibility, and communication skills that

understand Agency business are invaluable and in short supply in a crisis.

- Networking/Telecom, RDBMS, programming, GIS, web development skills are

all critical.

- Keeping equipment up-to-date is vital

- Establish internal and external roles and responsibilities and

coordination mechanisms in advance of a crisis, or as early as possible. Keep

staff with poor communication, planning and team skills out of key

coordination roles.

- Support development of an emergency response data management

infrastructure that will provide emergency response teams with the necessary

database and presentation tools to allow information to be efficiently

recorded in a standardized format, available for decision-making and made

accessible to the public.

- Replace paper driven data collection, data delivery and QA processes

with standards-based electronic processes that flow into data systems that

support rapid integration and analysis. Don’t take years to do this.

- Make data management and analysis an integral part of the data

collection planning process. Know why you are collecting information and

what you hope to use it for, and be aware of who else needs it. Secondary

use is often more important than your own internal needs.

- Presume that in a large emergency, public dissemination of critical

information is an integral part of your emergency response work - and plan

for it.

- Develop web templates for hazard information for important contaminants

in advance. Development of this type of text takes more time than

preparing the data.

- Develop secure Extranet means to facilitate sharing of data, data

services, and other information by responding organizations. Web services

and geoservices have a big role here. Run scenarios and test how to do this

in non-crisis situations.

- Have ability to rapidly collect remote sensed information in place in

advance. Define some standard delivery products that integrate well with

existing software and staff capabilities. Raw data or difficult to

understand remote sensing information is worse than nothing in a crisis.

- Work with multiple involved agencies to develop good metadata for shared

information

- Design information products for different audiences and media

- Graphic, easily understandable summaries of complex data invaluable

- Hard copy needed as well as electronic and web

- Need multiple mechanisms for dissemination

Conclusion

The varied elements of geospatial support for the World Trade Center response

have important implications for EPA and its partners. The lessons learned from

this experience will hopefully help the Agency prepare for the data management

and analysis demands of future events, establish the infrastructure to continue

operations when our own offices are affected by disasters, and prepare the means

in advance to facilitate interagency cooperation and data sharing in a crisis.

DISCLAIMERS AND COPYRIGHTS

The content of this paper does not necessarily reflect the position or policy

of the Environmental Protection Agency, nor does mention of trade names,

commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the Environmental

Protection Agency or the federal government.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

EPA's data and geospatial support for the World Trade Center was a highly collaborative effort with many participants making

significant contributions, including:

EPA Region 2

Roch Baamonde, Bonnie Bellow,

Yue-On Chiu, Robert Eckman, John Filippelli, Kenneth Fradkin, Bill Hansen, Barry

Kaye, Bob Kelly, Carlos Kercado, Bob Messina, George Nossa, Barbara Pastalove,

Harvey Simon, Robert Simpson, Stan Stephansen, Daisy Tang, Linda Timander, Erwin

Smieszek, Richard Stapleton, Raymond Werner

EPA Office of Environmental

Information

Debbie Villari, Dave Wolf, Julie Kocher

Systems Development Center

Adam Deer, Mash Eslami, Matt

Moss, Michele Passarelli,

Vincent Zhuang

EPA Office of Air Quality Planning and

Standards

Fred Dimmick, Dierdre Murphy,

Debbie Stackhouse, David Mintz

New York City Emergency Mapping Center

Paul Katzer, Allan Leidner

New York State Office for Technology

Bruce Oswald, Thomas

Henderson, Bill Johnson

New York City Department of

Health

Caroline Bragdon

EPA Region 4

Don Norris (Detailed to New York from Athens Lab)

Apologies to any of the many

others who helped that may have been inadvertently left off this list.

Harvey Simon

GIS Coordinator

United States Environmental Protection Agency Region 2Mark Gallo

On-Scene Coordinator

United States Environmental Protection Agency Region 2