One promising aspect of GIS mapping is its potential for addressing public safety concerns. GIS provides a quick method for establishing whether or not an offender residence is located in accordance with his or her state's laws. In an exploratory study, the registered addresses of convicted child sexual offenders are plotted and checked for violations of Illinois' prohibition against such perpetrators living within a 500 foot radius of schools and other designated areas. Any subjects within the forbidden perimeters will be highlighted, and the implications of such findings discussed.

Amid continuing clamor and pressure from the public to protect communities' children from criminal predation, law enforcement agencies are looking for effective tools to use in tracking, locating, and ultimately preventing offenders from repeating such crimes. Federal legislation, lobbied for by citizen child advocacy groups, has resulted in three laws enacted with the intent of aiding both police and the residents of their jurisdictions in this effort. The most highly publicized and controversial of these laws is Megan's Law (1996), which mandates states to develop protocols allowing public access to information about previously convicted sex offenders living in their community. Currently in effect, this law will face challenges to its constitutionality before the Supreme Court later this year. Of greater practical utility to law enforcement is the Jacob Wetterling Crimes Against Children and Sexually Violent Offender Registration Act, which imposes 4 obligations on each of the 50 states. This 1994 law requires that (1) states register all certified (convicted) perpetrators of crimes against minors, as well as those adjudicated sexually violent offenders. (2) Each state is charged with maintaining an accurate registry of such criminals. (3) Distribution of information contained in the registry is to be made by the state to law enforcement agencies. (4) The state will disclose to a jurisdiction's residents registry information about these categories of offenders when necessary for public safety. The last law germane to this issue is the Lynch Act, which requires the FBI to handle sex offender registration in states lacking what it termed "minimally sufficient" programs (Chaiken, 1998)

Of these laws, the registries created to meet the objectives set by the Jacob Wetterling Act, when combined with the use of a GIS mapping program, potentially offers law enforcement officials a cost effective first line of defense that so far many have overlooked. An obvious and realistic concern of police is the issue of compliance to their individual state's registration parameters. Though granted some latitude within the federal guidelines established by the Wetterling Act, a majority of the states set proximity limitations for these offenders, restricting them from living or loitering within a predetermined distance from schools, parks, daycare facilities, etc. The laudable intent of this aspect of the law is to keep the offender from gaining easy access to possible victims. But the question arises: do a majority of police departments routinely check to see if offenders' addresses violate the boundaries put in place by their state? The answer to date is no.

The investigation and enforcement of proximity restrictions on child sexual offenders and predators would be impossible for most jurisdictions to attempt by the time honored door-to-door footwork method. The required man hours for checking each registered home or apartment would be prohibitive, adding an unacceptable burden to agencies already charged with accomplishing more and more in the face of dwindling resources. Yet the need to enforce compliance is also pressing. Discovering too late that a registered child sexual offender had been living next door to a daycare center, and selected his or her victim from among the children cared for there would be a disaster for the victim, the community, and the police.

Checking offender compliance with residency restrictions without unduly encumbering law enforcement agencies and personnel became the focus for this study. Using the GIS Arcview mapping program in conjunction with a state's official register of child sex offender addresses, plots were made to ascertain whether or not each offender's dwelling space fell inside or outside the state's designated "off limits" areas. Illinois was selected as the sample state for this study.

To practically test the feasibility of this program application, a working knowledge of Illinois' legal directives regarding child sexual offenders' residency restrictions is required. This issue was addressed in amendments to Criminal Code 720 Illinois Criminal Statutes (ILCS) 5/11-9.3 and 5/11-9.4, respectively. The criminal code specifically prohibits child sex offenders from residing within 500 feet of a school attended by persons under 18 years of age, a playground, or a facility providing programs or services exclusively directed toward persons under 18 years of age. (An exemption is allowed for those offenders owning the property where they reside prior to the effective date the amendatory act took place, which is July 1, 1999.) Child sex offenders are also restricted by law from knowingly being present in or loitering on a public way within 500 feet of any school building, school ground, on a school conveyance used to transport students to or from school-related activities when persons under 18 years of age are present. It is also unlawful for such offenders to knowingly loiter on a public way within 500 feet of a public park building, or on real property comprising any public park. Further, child sex offenders are prohibited from approaching, contacting, or communicating with a child within public park zones. A "public park" includes a park, forest preserve, or any conservation area under the jurisdiction of the state or a unit of local government (Illinois Guide to Sex Offender Registration, 2001).

Based on Illinois' legal guidelines, 3 target zones were chosen for this work. Schools, parks, and recreational areas were plotted, with the corresponding 500 foot "off limits" boundaries outlined. These boundaries define the space specified in the law mandating the exclusion of child sexual offender residences.

Next, the Illinois State Police Sex Offender Registry (June, 2002) for all 102 counties in the state was obtained. There were a total of 12,730 offenders contained in the data base. Please note here that as of June 24, 1997 Illinois increased the scope of its mandatory registration to include all certified (convicted) sex offenders. From this listing, only those who were convicted of offenses against children (offenses having victims under the age of 18) were selected for inclusion in this study. The number of cases meeting the selection criteria totaled 10,946. Sex offenses that qualify the offender for registration under the 720 Illinois Compiled Statutes 5/

11-6: indecent solicitation of a child

11-9.1: sexual exploitation of a child

11-15.1: soliciting for a juvenile prostitute

11-17.1: keeping a place of juvenile prostitution

11-18.1: patronizing a juvenile prostitute

11-19.1: juvenile pimping

11-19.1: exploitation of a child

11-20.1: child pornography

12-13: criminal sexual assault

12-14: aggravated criminal sexual assault

12-14.1: predatory criminal sexual assault of a child

12-15: criminal sexual abuse

12-16: aggravated criminal sexual abuse

12-33: ritualized abuse of a child

Additionally, if any of the following offenses are committed against victims under 18 years of age, and the defendant is not the parent of the victim, and the offense was committed on or after January 1 of 1996:

10-1: kidnapping

10-2: aggravated kidnapping

10-3: unlawful restraint

10-4: aggravated unlawful restraint

Conviction for any of the above listed offenses or their attempt mandates offenders register. Under 720 ILCS 5/12-14.1 , such commissions or attempts require offender registration:

14.1: Predatory Criminal Sexual Assault of a Child

A-1: The victim was under the age of 13 and the offender was 17 years of age or over and committed an act of sexual penetration, or

A-2: When the victim was under 13 and the offender was 17 years of age or older and committed an act of sexual penetration and caused great bodily harm to the victim that resulted in permanent disability or was life threatening

Also included in the sample is described in 725 ILCS 205/10-5 (1.9) - Violations under the Criminal Code of 1961 10-7: Aiding and Abetting under Child Abduction Section 10-5 (b)(10), and Child Luring, 10-5 (b)(10). Registration again in mandatory for both those committing or attempting the crimes.

The last offenses found within the selected cases come under 730 ILCS 150/2 (1.10) are violations or attempted violations of the following crimes of the Criminal Code 0f 1961:

10-4: forcible detention, if the victim is under 18 years of age

11-6.5: indecent solicitation of an adult

11-15: soliciting for a prostitute, if the victim is under 18 years of age

11-16: pandering, if the victim is under 18 years of age

11-18: patronizing a prostitute, if the victim is under 18 years of age

11-19: pimping, if the victim is under 18 years of age

As previously stated, the original sample for plotting those with victims under 18 may have contained 10,946 offenders, but as the data was organized into specific computer fields for mapping, several problems were discovered. A majority of the counties had a number of individuals listed as child sex offenders that showed "UNK" as an address. Since child sexual offenders are required to register within 10 days of establishing residency with the police or sheriff's agency within the jurisdiction where they reside, these cases indicate a legal violation. While interesting to note, such cases obviously had to be dropped from the sample. Statewide, 576 cases fell into this category. Another problematic registration found in every county was the use of Post Office Box (POB) numbers. These designations do not provide the state required address for registration purposes, defeating the reason for creating the data base. Again, cases showing PO Box numbers could not be mapped. Rural Route addresses, while permissible for establishing an individual's place of residence, do not supply specific enough information to determine whether or not the offender's home violates the 500 foot boundary parameters (11 and 7, respectively).

Other cases excluded from the sample are those where the person inputting the information made an error and excluded the street address, the town, city, or Zip Code (91). Also, some of the offenders were listed as residing at various county jails either in or outside the city where the individuals were indicated as living (24). Again, these cases were excluded, as were cases where a person's only displayed address was "HOMELESS" (4), "AWOL" (3), "TEMPORARY HOUSING" (1), and "SALVATION ARMY" (1). Once these problem cases were culled from the sampling pool, a total of 10,228 cases met the criteria for research purposes prior to geocoding the data.

After the initial mapping run, 46 more cases could not be matched by geocoding. There are several possible factors that can account for these missing cases. Even though legally required to bring some form of documentation to verify their place of dwelling, offenders could still find ways to supply a false or fictitious address. Even more likely, whoever entered the information made a mistake when typing in the location. Another possibility that was noticed by the researchers was the wide variation in abbreviations that were present in the data, making it more difficult for the computer to match the actual location with the reported addresses. These cases also were removed from the sample, leaving 10,182 offender locations for testing purposes.

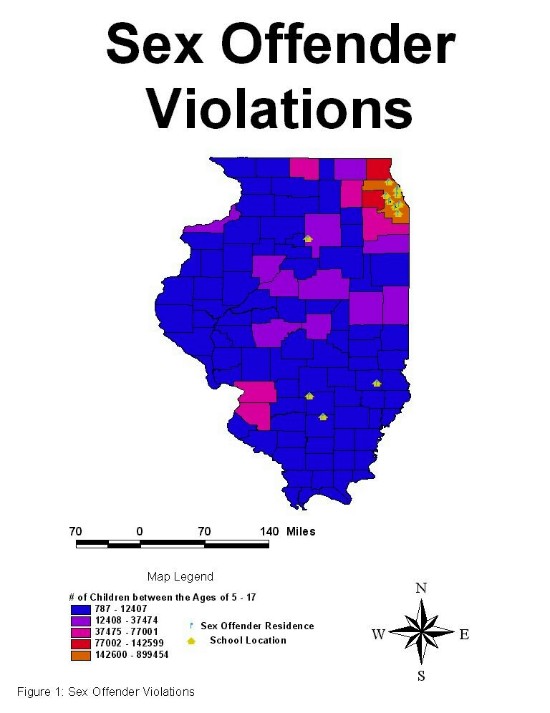

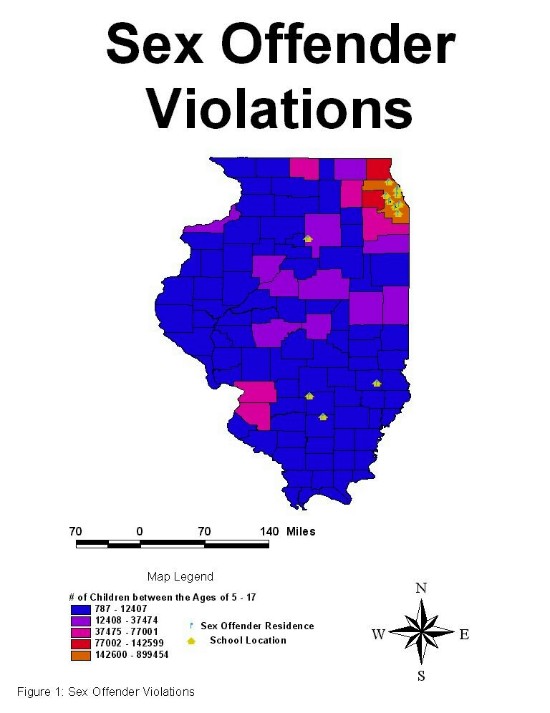

Results from overlaying the official offender registration data with the Arcview mapping program displayed 361 people living within 500 feet of one of the target zones chosen for study. These 361 offenders lived in violation of the boundaries of 13 different schools. No violations were mapped in conjunction with parks or recreational areas. Figure 1 displays the 5 counties in which the violations appear: Cook, LaSalle, Jasper, Marion, and Jefferson.

Once the 361 violations are divided among the counties, then jurisdictions where they appear, the follow-up to check the circumstances surrounding the apparently unlawful addresses is a much more manageable task for individual law enforcement agencies. Some of these cases will fall under the only exemption extended to offenders: in Illinois, child sex offenders who owned the property where they reside before July 1, 1999, are permitted to live in that residence. The matter of ownership, and date it was established can easily be checked. Other cases will prove to be in direct violation of the law.

Another advantage of mapping the offenders addresses by each jurisdiction is allowing each department to review the accuracy of their data and its entry. A glaring problem discovered by this study was just how incorrect and incomplete the data contained in the sex offender registry is. Checking over their registry information will aid departments in meeting one of the mandates of the Wetterling act, which requires jurisdictions to keep an accurate registry. If perusal of the registry information shows incomplete or even impossible addresses, the matter can be rectified. This step also refocuses agencies on dealing with offenders who attempt to offer only a post office box number rather than an actual place of residence. Additionally, the procedure of reviewing the data for mapping can provide information to be passed on to patrol officers about offenders with "UNK" instead of addresses, and follow-up encouraged.

And finally this procedure allows each police department to demonstrate to their community that they are committed proactively, tangibly, to regulating sex offenders who have been released into their communities. While creating and enforcing the so-called "no pervert" zones around schools, daycares, and other youth- oriented facilities may, in part, be more public relations than public safety, it still offers law enforcement a valuable tool when sex offenses do occur. Yes, it is important to know where a community's sex offenders live. As a group, sex offenders are known to be very likely to recidivate (Klaaskids Foundation, 2002; Matson and Lieb, 1996). The knowledge of the proximity of known sex offenders to sex crime locations can be vital for investigations of this nature. Mapping out the sex offender registry, removing violators, checking the accuracy of information in the registry are all valuable and cost effective tools any police department can use to help safeguard its community's children.

Chaiken, Jan M. (April 1998). National Conference on Sex Offender Registries: Proceedings of a BJS/SEARCH Conference [on-line]. http://www.obp.usdoj.gov/bjs/pub/pdf/ncsor.pdf [NCJ-168965].

Esri (1996). ArcView GIS (Version 3.1) Redland, CA: Environmental Systems Research Institute, Inc.

Illinois State Police (June 2002). Illinois Sex Offender Information [on-line]. http://www.samnet.isp.state.il.us

Illinois State Police (September 2001). A Guide to Sex Offender Registration in Illinois [on-line]. http://www.isp.state.il.us/docs/sorguide.pdf

KlaasKids Foundation (June 2002). Megan's Law by State [on-line]. http://www.klaaskids.org/pg-legman.htm

Matson, Scott and Lieb, Roxanne (July 1996). Sex Offender Registration: A Review of State Laws [on-line]. http://www.wsippa.wa.gov/reports/regsrtn.html

| Kenneth

A. Clontz, Ph.D. Associate Professor Western Illinois University Department of Law Enforcement and Justice Administration Stipes Hall 403 1 University Circle Macomb, IL 61455-1390 Office Phone: 309-298-2251 Fax: 309-298-2271 E-Mail: KA-Clontz@wiu.edu |

J.

Gayle Mericle, Ph.D. Associate Professor Western Illinois University Department of Law Enforcement and Justice Administration Stipes Hall 403 1 University Circle Macomb, IL 61455-1390 Office Phone: 309-298-1928 Fax: 309-298-2271 E-Mail: JG-Mericle@wiu.edu |