Presentation at the 1999 Esri International User’s Conference in San Diego, CA

ABSTRACT

Woolpert has developed a fast, efficient, and cost-effective method for field data collection of infrastructure inventory using ruggedized pen-based PCs. The process uses a core database engine, customized with application-specific interfaces and processing routines, and emphasizes verification of data as it is collected. The process involves two principal steps: GPS surveying of point features, and feature attribution. During the first step, a foundation database is created with GPS-determined x,y,z locations and basic external attributes of each structure (such as structure type). Special programs have been developed to automate transfer of the GPS data directly from the receiver and to expedite input of the attributes. Detailed attribution requiring opening of the structure (i.e., inverts and condition) is performed during the second phase, as well as collecting digital photography and adding connecting pipe features. Customized software transfers attribution from structures to pipes as appropriate, creates a spatially related GIS database structure, and employs built-in quality control measures.

Communities are finding that managing utility infrastructure is becoming an important issue. Specifically, the need for conducting a storm water infrastructure inventory is becoming necessary. This paper will discuss the reasons for performing a storm water inventory, explain considerations when locating storm water structures using global positioning systems (GPS), and discuss system design and management issues when conducting a field inventory.

There may be several reasons a community would want to conduct a storm water infrastructure inventory. One reason may be the community is required to conduct an inventory according to their National Pollutant Discharge and Elimination System (NPDES) permit, which may consist of, at a minim, locating outfalls of storm water systems. Another reason may be to perform hydraulic modeling for solving problems related to flooding of certain areas. A community may desire to implement a proactive maintenance plan to repair its aging storm water infrastructure before its residents complain of flooding due to inoperable or over-burdened storm water structures. Yet another reason may be to map and model the infrastructure in order to determine if the storm water infrastructure can support future land use changes according to the community’s master plan in order to determine best locations for capital improvement projects (CIP).

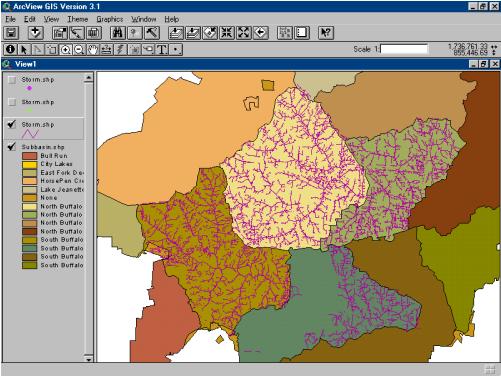

Map showing watershed boundaries and storm water infrastructure inventory. Note that closed storm water system should not cross watershed boundaries.

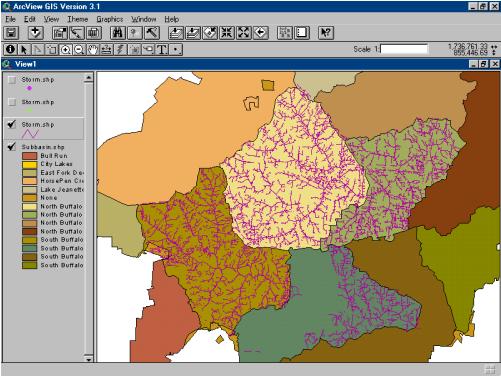

The primary tool for the electronic storage of the inventory is a pen-based field computer. There are several manufactures of pen-based computers and the community’s choice should be based on how it will be used. As a rule, the best pen-based computer for most situations is one that runs Microsoft’s Windows ’95 or Windows ’98, has at least 4GB of hard disk space, 32 MB of RAM, has serial and parallel ports or a USB port, has a relatively speedy processor (233MHz), and is rugged and light enough for field use.

Pictures showing a pen-top computer (left) and a pentop computer with a GPS receiver connected to it (right).

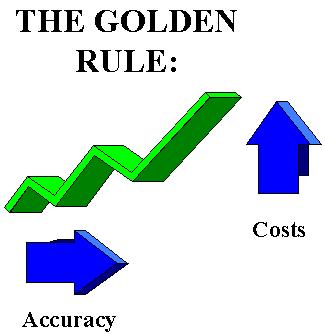

Of all the attributes that a community will collect for the storm water structures, the location will be the most time consuming and costly. Accurate location is very important for mapping storm water systems and especially important when locations will be used for modeling. A guiding principle is that as the accuracy of the location increases, cost increases. There are several methods to locate storm water structures. Each method involves either a one-pass or two-pass approach. A two-pass approach is when structures are attributed in two passes by two different crews. The first crew is a survey crew that locates the structures using GPS or total station. The second crew follows and attributes the located points. In the one-pass approach, the same crew performs both the location and attribution of the storm water structures. There are benefits and limitations to both approaches. In the one-pass approach, there is no need to label structures for a second crew to find, the system is built on-the-fly and so quality control algorithms can detect errors in measurement or location before the crew leaves the site, and the crew can more easily find any omissions of structures since they will be opening each structure and viewing the system. The two-pass approach, on the other hand, is more cost-efficient since a survey crew can collect considerably more locations than an attribute crew can. Another consideration is the desired locational accuracy. Differential GPS (DGPS) can achieve an accuracy of ± 1 meter whereas real time kinematic (RTK) GPS can attain a very high level of accuracy around ± 5 centimeters. There is a considerable cost increase when using RTK GPS over DGPS. Despite the method of GPS used, there will most undoubtedly be some points that survey crews cannot locate due to obscurations. Trees, buildings, and terrain can mask a signal path to one or more satellites. Therefore, alternate means of survey may have to be employed such as total station or triangulation. The best type of approach and GPS technique for a community depends on its needs and available resources. A community may also want to consider a hybrid approach such as performing highly accurate survey on hydraulically sensitive features in the storm water system such as culverts and perform lower accurate survey on incidental systems such as small pipes of 18 inches or smaller. This type of hybrid approach may appeal to a community whose primary objective is to perform hydraulic modeling, but has a very limited budget.

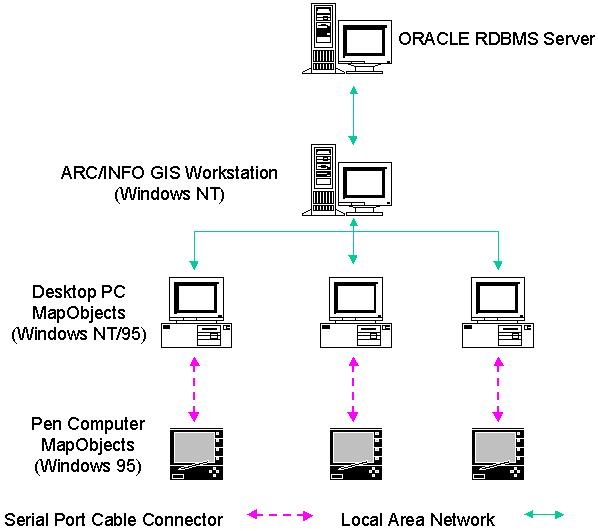

A well-formulated plan before going to the field is extremely important. A community must develop a comprehensive database design, develop procedures, and derive table definitions based on the attributes desired. As the number of database fields increase, the time and cost associated with collecting the data also increases. The type and number of data entities should be based on how the community wishes to use the information. Attributes such as condition, type of structure, and constructed material can aid in developing proactive work-orders and dispatch repair crews with the proper personnel and equipment. If the goal of the field data collection effort is for hydraulic modeling, then a community should ensure that all the required parameters for the hydraulic model are included as fields. A data flow plan and field procedure is extremely important. Strict conventions for capturing data should be imposed on field crews in order to ensure data consistency. An example data flow plan is shown below. Also, managing database transactions can be especially challenging when data is replicated to field computers and many field crews are downloading and uploading updates.

Diagram showing an example of data flow in a field GIS.

Strict adherence to standardized data flow procedures is very important. The development of field procedures is also very important. Field crews should obey standardized conventions for the location of the GPS shot and subsequent measurements from the shot. For example, a standard may be to take a GPS shot at the very center of a grate and measure from that point perpendicularly down to all the pipe inverts. It is essential that people follow the procedures developed in the inventory plan.

Picture showing a member of attribute field crew measuring down to a pipe invert from the GPS shot.

Pictures showing examples of GPS shot locations and other attributes to collect during a storm water infrastructure inventory.

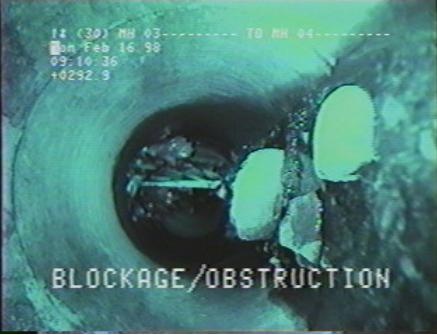

Data entry may be done on the pen-top computer using off-the-shelf software or custom software. Whatever software a community decides to use, it should have the ability to perform quality control checks such as ranges of values for fields and network connectivity checks in order to minimize checks in the office and repeated trips to the field. It should also be configurable so as to to allow the user to capture data according to the database design. Besides textual attributes, other types of data may be collected for a structure. For instance, a digital picture or video of the structure can communicate much about an anomalous structure. Pictures can be taken from the surface or, as shown below, taken from underground.

Video still of inside a storm water pipe showing an obstruction that would be important to maintenance and hydraulic modeling staff.

Every systems developer should consider the hardware, software, data, people, and procedures when designing and implementing the geographic information system. In a field environment, these considerations become especially critical to the success of an infrastructure inventory. The people and procedures components of the GIS are perhaps the most important. People must understand the system design and follow established procedures in order to create a successful infrastructure inventory.

Gilbert B. Inouye

Project Engineer

Woolpert LLP