Hugh Irwin

Protecting Biodiversity Through a Network of

Conservation Areas in the Southern Appalachian Region

Abstract

The Southern Appalachian Forest Coalition (SAFC) is developing conservation plans centered on public lands in the Southern Appalachians. A crucial part of this process involves local groups and citizens in identifying conservation and heritage resources, setting conservation priorities, and placing local conservation prospects within a landscape perspective. SAFC has created new GIS resources to facilitate work with grassroots groups and communities. Conservation areas have been identified throughout the region, showing conservation opportunities and issues in and around these areas. Conservation area designs are being integrated using GIS into a proposal for a network of conservation areas throughout the region.

Introduction

The Southern Appalachian region is rich in natural and cultural history. It has witnessed millions of years of evolutionary history, has served as the center of evolution for species, and has served as a refugia during periods of climatic change. Within human history it has served as home to indigenous people in a complex inter-relationship that took advantage of its abundant natural resources and processes. More recently, European settlers struck a balanced relationship with the land that still preserved its basic processes and rich biological diversity. It was only in the last century that industrial logging and wide scale development has thrown the ecological dynamics of the region into jeopardy. The region has considerable dynamic resilience and has shown a remarkable ability to recover. However, if the region is to retain its rich biological heritage of diversity, it will be necessary to plan for this within a context of protection and sustainability for the modern world.

The Southern Appalachians

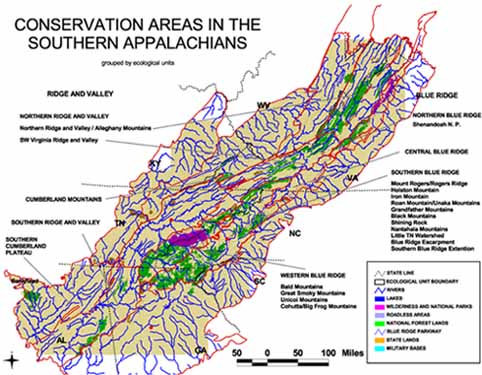

The Southern Appalachian region encompasses over 38 million acres in the mountainous portion of 6 states ranging from Virginia to northwest Alabama (Fig. 1).

Fig 1 Southern Appalachian Region

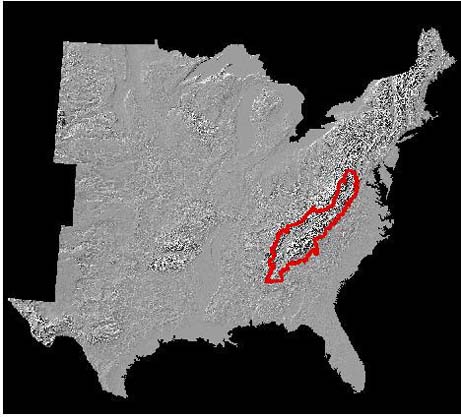

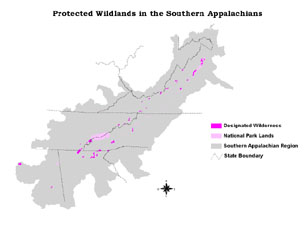

The region contains some of the most consolidated and unfragmented ownership of public lands in the eastern US with over 4.5 million acres of national forest 0.6 million acres of national park, and significant amounts in state and other ownership with potential for planning and conservation protection. A significant amount of this land is designated wilderness or is inventoried as roadless (Fig 2)

Fig 2 Designated Wilderness and Inventoried Roadless areas in the Southern Appalachian Region

The Roots of Protection and Restoration in the Southern Appalachians

The roots of the protection and restoration effort in the Southern Appalachians extends back 100 years. At that time destructive logging was already beginning to take its toll. A series of devastating floods that came in the wake of over-cut watersheds and devastating wildfires that started in the slash left from large clearcuts raised the alarm of regional and national leaders. A few visionary leaders saw the need to save forests that had not been devastated by destructive logging and to recover watersheds in the region. This effort resulted in a movement that established national forests in the east (1911), established Great Smoky Mountains National Park (1934), and established Shenandoah National Park (1935). Current conservation efforts and planning is a continuation and completion of the effort begun a century ago by these ancestors of vision.

Aspects of Biological Diversity in the Southern Appalachians

The Southern Appalachians have experienced a long period of relative geologic and climatic stability. While other areas have been submerged under seas, have been subjected to glaciation, or experienced other geological and climatic extremes, the southern Appalachians have experienced a remarkable period of relative stability. Mountains that first arose 230 million years ago have gone through stages of uplift and erosion, giving rise to a very complex topography that provides numerous micro-habitats where specialized plants and animals survive. It also has a continuum of habitats. During Pleistocene glaciation (3 million to 18,000 years ago) this continuity of habitat allowed plants and animals to move up and down mountain slopes and riparian corridors, as well as north and south along the mountain chain to adapt to the changes in climate. The ice sheets which lay hundreds of miles to the north of the Southern Appalachians altered the climate in the Southern Appalachians, but there were gradients of habitat and habitat niches that allowed species to find suitable places to survive during this period of change. When the glaciers melted, this same complex of habitats allowed species now more characteristic of northern climates to remain in the region as disjunct species.

The region has been continuously vegetated for over 100 million years, spanning the evolution of flowering plants. Because of its long evolutionary history, its relative stability, and its complex range of habitats the region serves as a refugia. The region has served to preserve many species from the ancient Arcto-Tertiary forest, was repository and conservator of many species from the ice ages, and it also has many species from the great oak forests that arose in dry periods before the Pleistocene.

Because of this complex and rich history the region is a center of plant diversity. Over 3,000 species of flowering plants occur in the region. These include endemics, species occurring within a narrow geographic and sometimes narrow ecological niche, and disjunct species, species occurring far from their main range with no occurrences in the intervening territory. It is important to note that disjunct species have been found to contain much of the genetic variation of the species. It is also worth noting that disjunct species far from being just "outlying populations" are suspected in many cases, including those in the Southern Appalachians, to be the parent stock that repopulated northern areas after glaciation.

The headwaters for many high aquatic diversity rivers have their origins in the Southern Appalachian mountains. Several river systems in the south, including the Tennessee and the Coosa have globally significant aquatic diversity. Although much of this diversity is found in lowland areas outside the mountains, this diversity is dependent on water flowing out of the mountains. Because of dams and pollution in the lowlands, many of these species also only survive in the transition between mountains and lowlands. Thus the Southern Appalachians play a key role in preserving this diversity for the future.

The Southern Appalachians are a center for salamander diversity. One group of salamanders, the Plethodons find their greatest diversity and expression here and it is suspected that the southern Appalachians are their center of evolution.

Over 120 species of trees are found in the region.

Objectives of Conservation Planning

- Represent in a system of protected areas, all native ecosystem types and seral stages across their natural range of variation.

- Maintain viable populations of all native species in natural patterns of abundance and distribution.

- Maintain ecological and evolutionary processes, such as disturbance regimes, hydrological processes, nutrient cycles, and biotic interactions.

- Manage Landscapes and communities to be responsive to short-term and long-term environmental change and to maintain the evolutionary potential of the biota.

(1 Noss and Cooperider 1994)

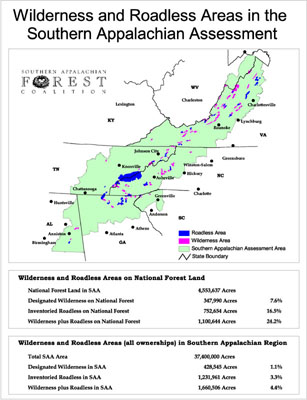

Conservation Planning Involves Looking at Projects from Both the Landscape and from the Regional Perspectives

Fig 3 Work at the Landscape level informs work at the Regional and Project levels. These levels in turn fill in important information at the Landscape level.

Interaction between an overall conservation vision and specific conservation work

An overall conservation vision is important to guide specific conservation projects in order to keep a focus on the long term. On the other hand the conservation vision should be open to benefit from information and perspectives coming from individual conservation projects.

Fig 4 The conservation vision informs work on conservation projects; work on conservation projects enriches the conservation vision with detail.

Working With Regional and Local Partners in Conservation Planning

Fig 5 Meetings to help define, incorporate detail, and build support for landscape conservation areas

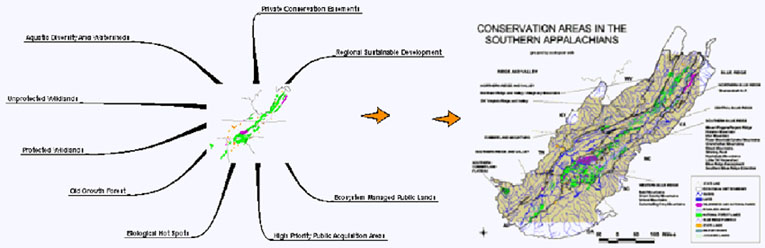

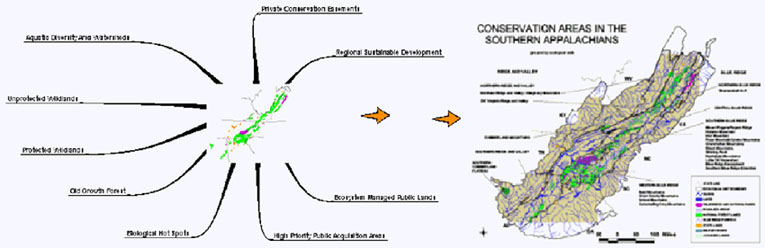

Elements Making Up the Regional Conservation Plan

Conservation Area Elements

- Protected Wildlands

- Unprotected Wildlands

- Old Growth Forest

- Biological Hotspots

- Aquatic Diversity Area Watersheds

- High Priority Areas for Public Acquisition

- Conservation Easements

- Cultural/Heritage Areas

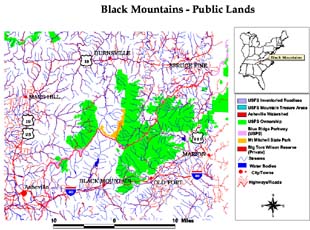

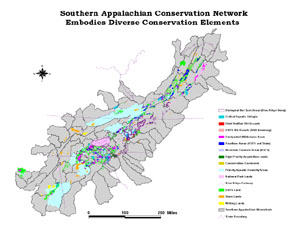

Fig 6 A number of conservation elements together make up the overall conservation plan

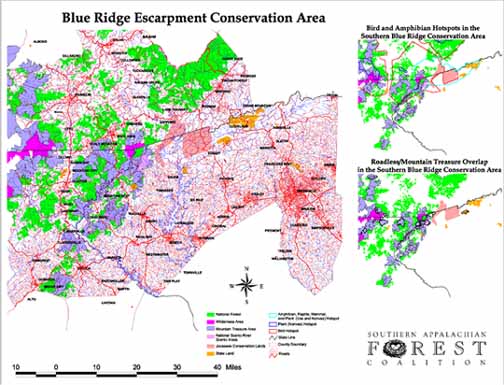

The Regional Conservation Plan is Composed of Landscape Conservation Areas

Fig 7 Within the regional conservation plan, landscape conservation areas reveal much of the detailed ownership/management patterns and relationships

Overview of Landscape Conservation Areas in the Southern Appalachian Region

Fig 8 SAFC and its member groups have identified a number of landscape conservation areas throughout the Southern Appalachians

Conservation Plan Element: Protected Wildlands

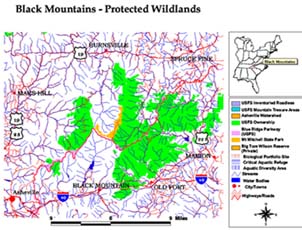

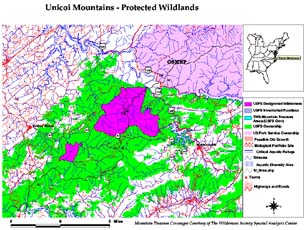

Fig 9 Protected wildlands in the Southern Appalachians and in two landscape conservation areas

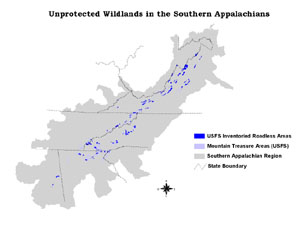

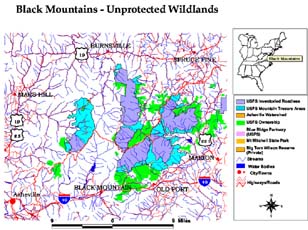

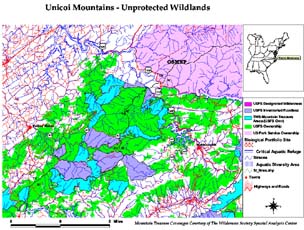

Conservation Plan Element: Unprotected Wildlands

Fig 9 Unprotected wildlands in the Southern Appalachians and in two landscape conservation areas

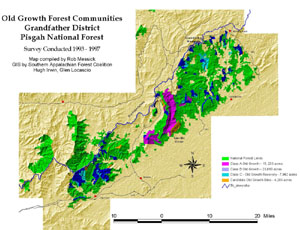

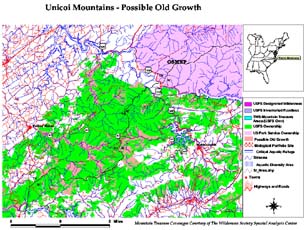

Conservation Plan Element: Old Growth Forest

Fig 10 Old growth inventories in two landscape conservation areas

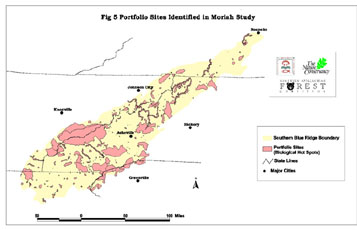

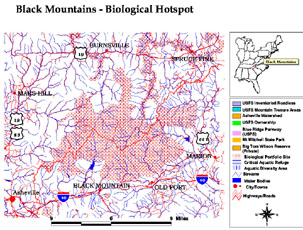

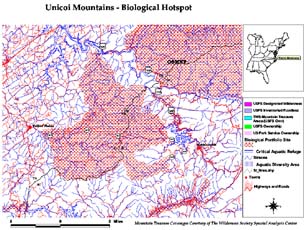

Conservation Plan Element: Biological Hot Spots

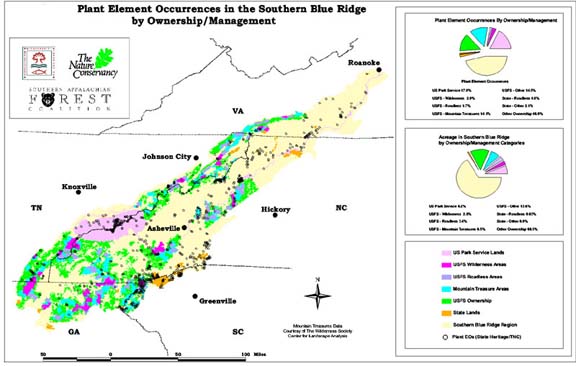

SAFC undertook a study with The Nature Conservancy, and state heritage programs to identify biological hot spots in the Southern Blue Ridge, a portion of the Southern Appalachians. This study made use of element occurrence data and expert meetings to identify hot spot areas important for viability of rare species in the region. The study is currently being extended to other areas of the Southern Appalachians.

Fig 10 Identification of Biological Hot Spots in the Southern Blue Ridge (sub-region of southern Appalachians) and hot spot areas in two landscape conservation areas.

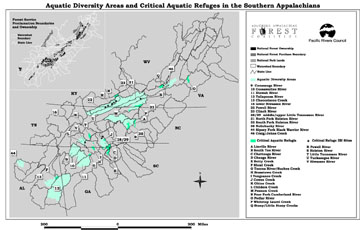

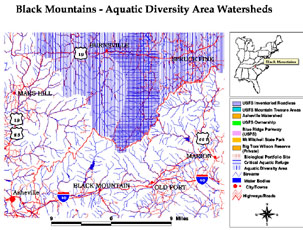

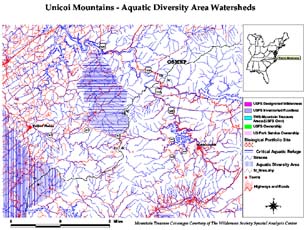

Conservation Plan Element: Aquatic Diversity Area Watersheds

Fig 11 Regional identification of Aquatic Diversity Areas (ADAs) and Critical Aquatic Refuges (CARs); ADAs and CARs in two landscape conservation areas

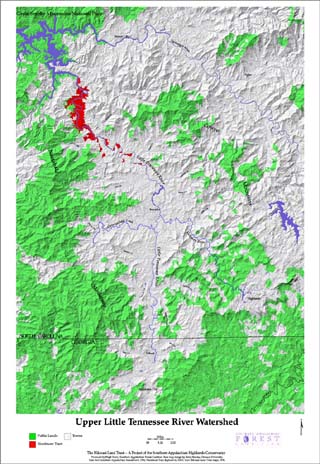

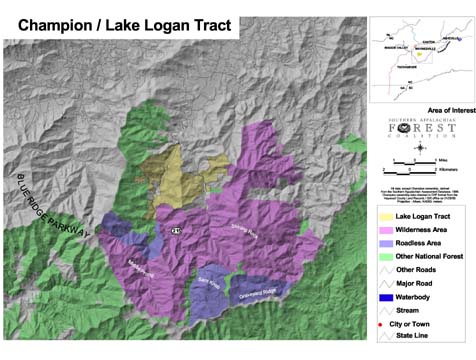

Conservation Plan Element: High Priority Areas For Public Acquisition

Fig 12 Areas in private ownership can have habitat as important as existing public lands; many of these areas are currently going on the market

Fig 13 Examples of two tracts that are being discussed for public acquisition

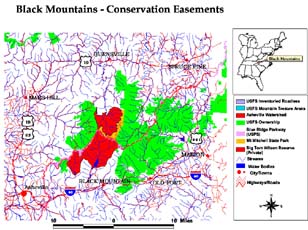

Conservation Plan Element: Conservation Easements

Fig 14 Conservation Easements can make a profound difference in how well a landscape area functions as habitat on the landscape. Landscape conservation area shown without and with conservation easements.

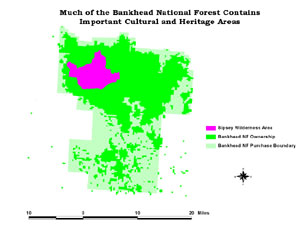

Conservation Plan Element: Cultural/Heritage Areas

Fig 15 Cultural areas can represent lands where traditional practices dominated in the past. These practices can be compatible with conservation purposes and can provide valuable habitat.

Conservation Elements are used to Construct the Conservation View of the Region

Fig 16 Conservation elements comprise the regional conservation view of the region

Conservation Elements in the Regional Conservation Network

Fig 17 The conservation elements together comprise the basic regional conservation overview. Broad regional patterns, issues of connectivity, and gaps are apparent at this level.

Putting The Conservation Elements Together on the Landscape

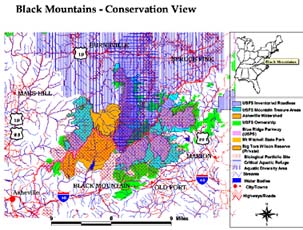

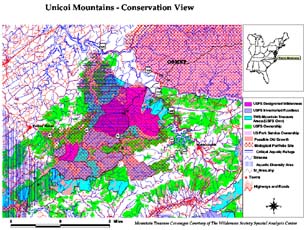

Fig 18 Two examples of landscape conservation areas with conservation elements displayed. At the landscape level the relationship between the different conservation elements and the roles they can play on the landscape become apparent. Connections to nearby conservation areas, gaps in connectivity, and conservation priorities can be examined in detail.

Representation of Biological Species and Communities in Conservation Elements

One of the major issues left to evaluate is the degree that the conservation elements (separately and together) represent all habitat types and capture rare species and communities. SAFC has begun this evaluation. Fig 19 shows the percentage of rare plant occurrences found in several of the conservation element categories used. This evaluation will also include animal and community rare occurrences. We are also evaluating representation of forest types both regionally and within landscape areas. This evaluation will help determine what habitats may be underrepresented. This will guide further iterations of landscape and regional conservation planning.

Fig 19 Representation of rare plants in different ownership/management categories. This is one way to evaluate how well rare species would be protected by the conservation plan.

Conclusions

Important conservation elements identified on a regional basis and also by landscape conservation areas were layered to produce a regional conservation view of the Southern Appalachian region. The landscape areas are being examined in detail to identify landscape relationships and ecological opportunities and issues. Representation analysis is being performed to guide future refinements of conservation planning in the region.

References

1 Noss, Reed F., Cooperrider, Allen Y. (1994), Saving Nature's Legacy: Protecting and Restoring Biodiversity, Island Press, Washington D.C.

Author Information

Hugh Irwin

Conservation Planner

Southern Appalachian Forest Coalition

46 Haywood Street

Suite 323

Asheville, NC 28801

email:hugh@safc.org

(828) 252-9223 FAX (828) 252-9074

Internet: www://safc.org