|

|

|

|

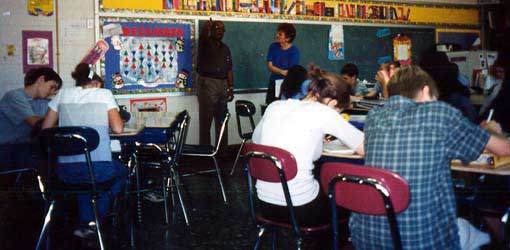

potential interviewees with Ms. Mackie |

|

|

|

|

potential interviewees with Ms. Mackie |

An active alumni association from Ligon High School met on December

2, 1998, with teachers at the middle school that now occupies the building.

Early discussions on how to reconstruct the school's history developed

several initiatives that became integrated as an interdisciplinary school/community

project. Alumni contributed information, yearbooks, and other resources.

Our State of North Carolina Archives partner guided us in policies about

publication of archival materials. Many of the images used were considered

in the public domain, including those from yearbooks pre-dating a 1962

ruling. The alumni have an active interest in the web archive, seeing it

as a way to preserve their history.

|

|

demonstrate oral history interview techniques. Mr. Hunter is describing landmarks in the community. |

Alumni and Dr. Wilson demonstrated oral history interviewing techniques to the middle school students that would conduct the first round of taped interviews. Using the videotaped demonstration as a model, students in the journalism compiled a list of questions to ask in future interviews that encouraged alumni to share their memories of LHS, the influence of segregation and integration in their lives. Pairs of journalism students facilitated by a graduate student, teacher, or professor conducted fourteen videotaped interviews that are published as Capturing the Past to Guide the Future.

Students in the Ligon Historians class learned interview techniques by viewing a tape of the demonstration. They studied a biography of Mrs. Jessie Copeland, a leader in the community surrounding Ligon, to formulate questions for a personal interview. Students interviewed Mrs. Copeland in the Copeland Center, a resource distribution center located in the public housing project adjacent to the school. The focus of this interview was to record the history of Chavis Heights, the nearby federal housing project.

Students in the GIS class also viewed the demonstration tape to learn

interview techniques. They formulated geographic questions to elicit information

used to create GIS data layers. From interviews with Mr.

Leonard Hunter and Mr. Bob Rogers, information was combined with interviews

conducted by the other classes and research from books and primary sources

to create a prototype map of Raleigh in the 1950ís.

|

|

|

In a fall meeting, teachers and professors planned their collaborative efforts, setting production goals and target dates. Committing to paper, the partners revealed their planned activities and listened to one anotherís plans in order to coordinate efforts. During this meeting, a critical question was posed about the role of GIS in the project. As we talked about the various activities related to LHS history, Hagevik asked, "Well, what does GIS have to do with this? What can we do with GIS that we can't do in some other format?" These became our critical challenges. Specifically we identified our problems as:

|

|

|

meet with professors, graduate students, and an archivist/author in "talking stick" style sessions |

A project of this magnitude and diversity required that collaborators communicate effectively. Meetings of the middle school teachers, students, and principal, university professors, graduate students, an HBC professor and author were held monthly and audio taped. The teachers described the meetings, which took place as part of the graduate Historiographic Methods course, as critically important. At each meeting, each participant described and updated the research he or she was doing, and at each meeting, the university faculty and students asked the teachers what could be done to support the project. In the process of conducting this and archival research, the graduate students practiced accessing archival and other types of data and documentation common to researching school histories. A historiographic methods book from the Nearby History Series was used by both graduate and middle school students. (Butchart, 1986)

In listening to one another, we learned a great deal as well. Deeper respect for differences in perspectives and different avenues of research evolved as we shared information. More than just sharing information, the "go-around" was powerful in developing from each of our voices a collective voice. Most of the partners essentially worked in their own settings with periodic collaboration with another partner. But when the large group gathered as a whole, the very sounds of our voices were put into the large circle where we observed one another observing one another; heard one another hearing one another, and supported one another with information. The exchange of ideas, progress, and contributions inspired us. Essentially we reconnected with the project as a whole. The meetings emerged as necessary, useful, and helpful, and in the end, central to our continued progress. In the large group, middle school teachers, students, their principal, graduate students and professors all had equal time to speak as we went around the room "talking stick" style. The teachers expressed how important the meetings were to their in-school collaboration, "You know, those meetings were really helpful - they were a wonderful way to hear each othersí ideas. I'm going to remember that when I do cooperative group projects. It helped to hear what everyone else was doing and to spin new ideas off of one another." (Owens, personal communication).

Because collaborators only gathered monthly, the function of Email in the project was critical. The Principal Investigator established an inclusive mailing list, and most of the teachers and university partners had and used email accounts with frequency. Messages were posted to all of the participants to keep abreast of the various activities that radiated from the project. As a result of hectic and often mis-matched school schedules, Email was an important communication tool. Teachers, professors and graduate students were the most frequent users of email for the project. Many LHS alumni did not have Email. This can be a major hurdle in a school project where time and telephones are limited. The project also had its own Email address. This was published in the newspaper and on the web site. Six alumni connected with the project through Email. Two of these established continued exchanges with the technology teacher that yielded valuable input for the project and developed into personal relationships.